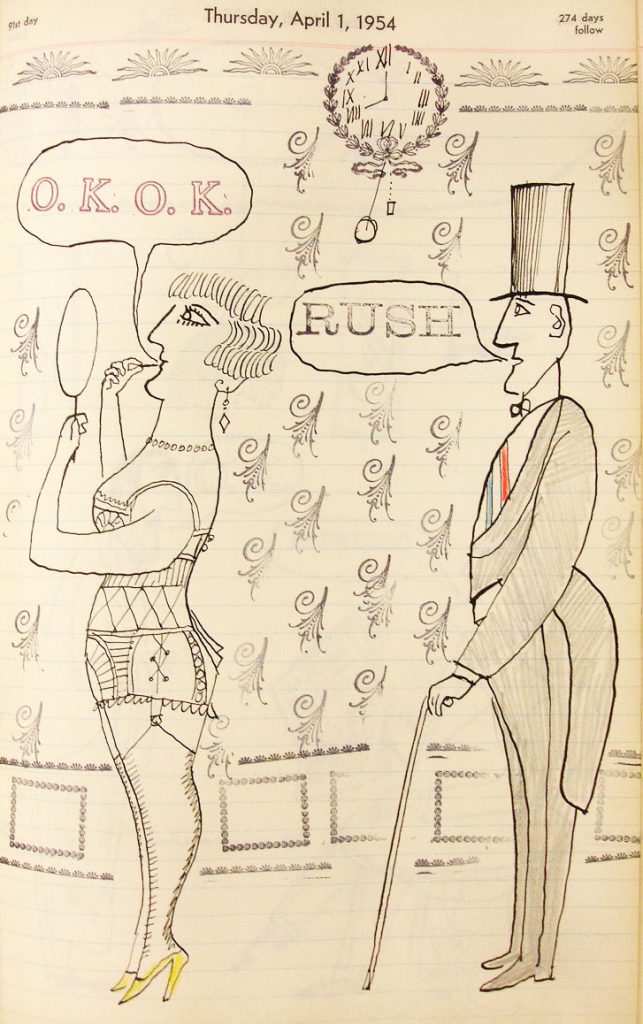

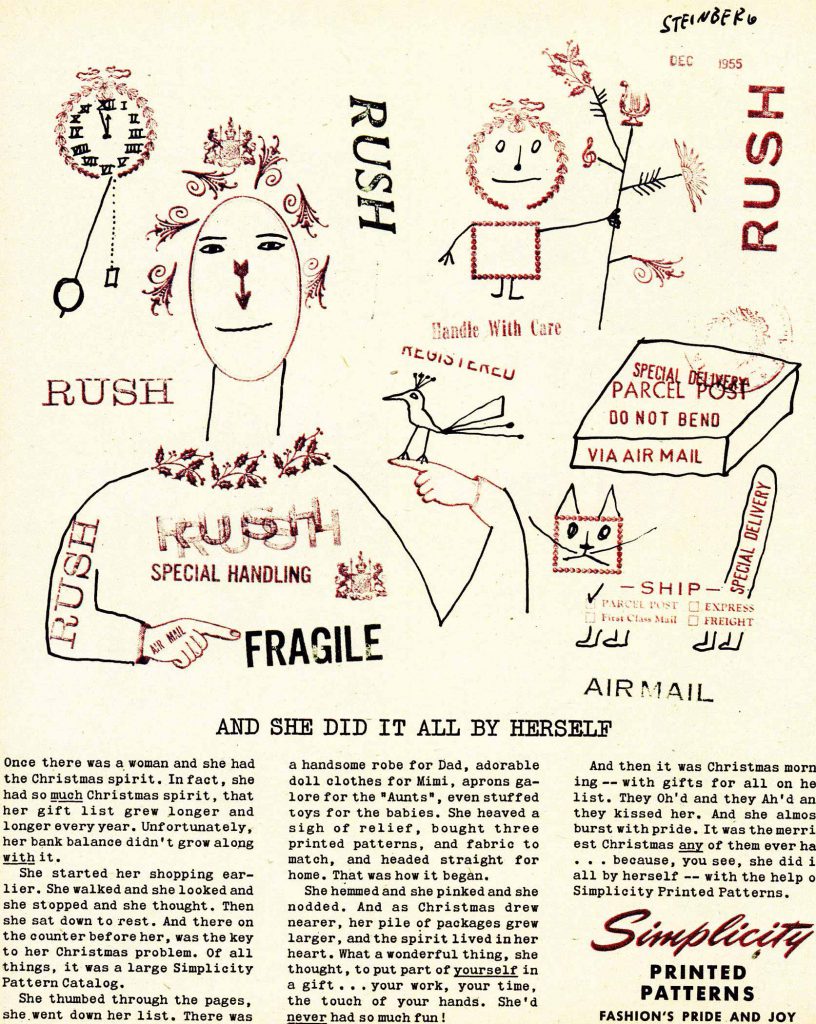

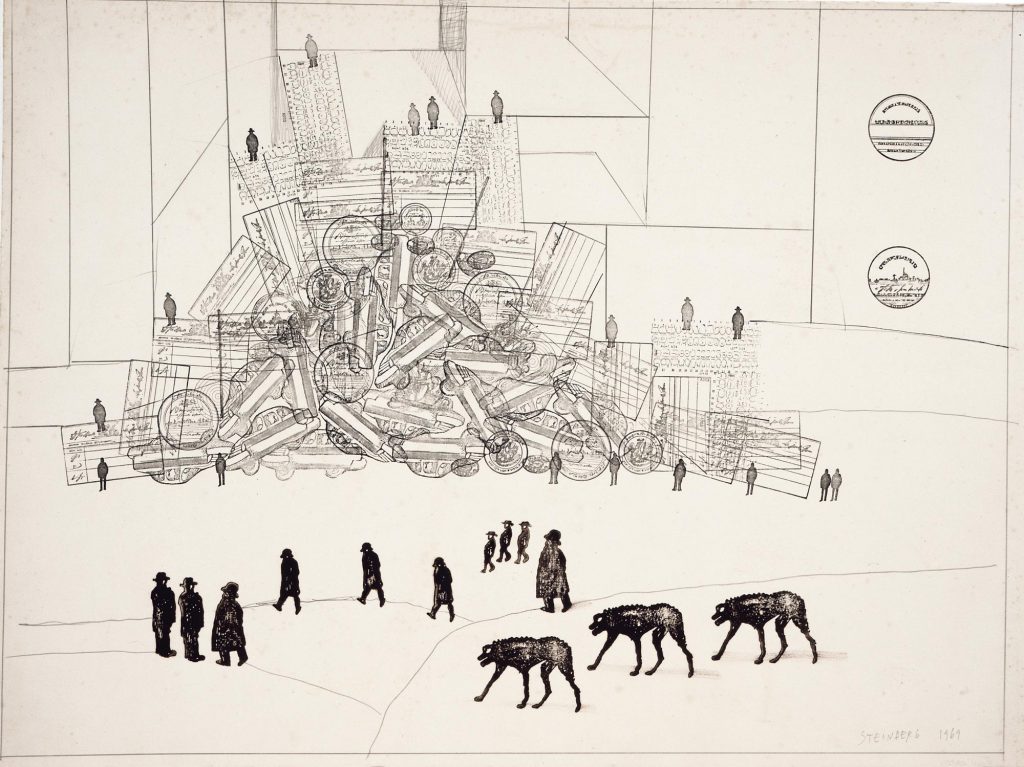

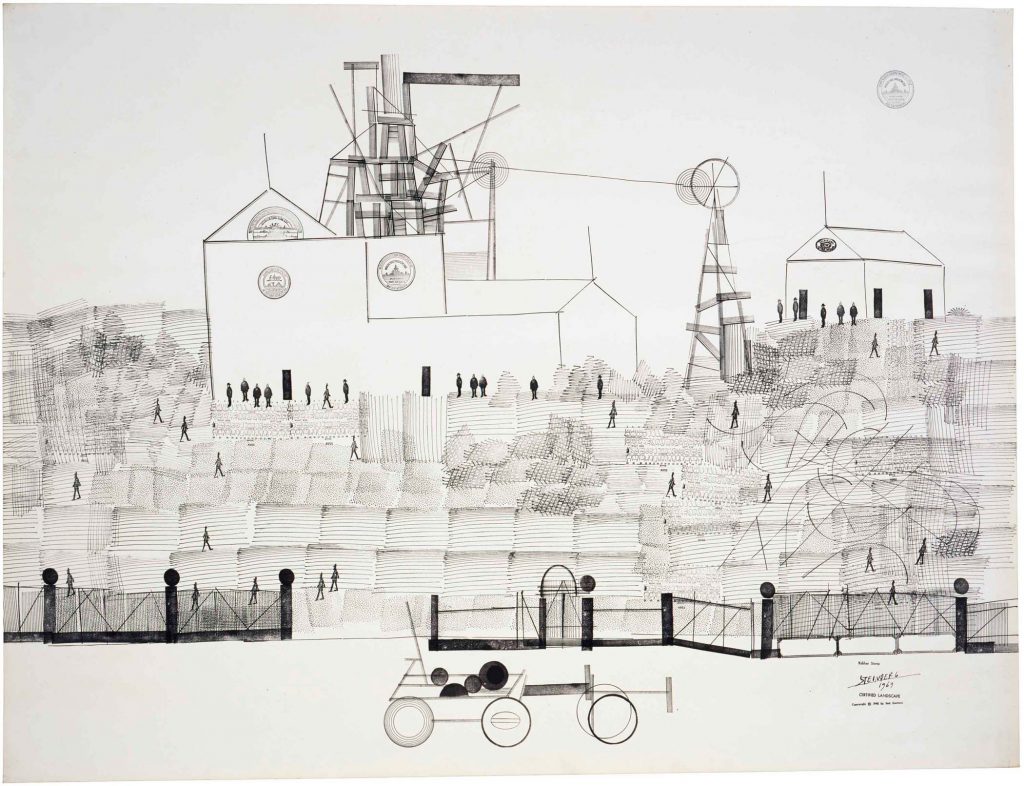

Rubber stamps, a characteristic Steinbergian device, had entered the vocabulary of his art around 1951, when he began to contextualize drawings with the addition of ready-made stationer’s stamps, often used anecdotally to create a slyly critical or vaguely threatening narrative.47

Such stamps even helped pitch commercial advertising messages.

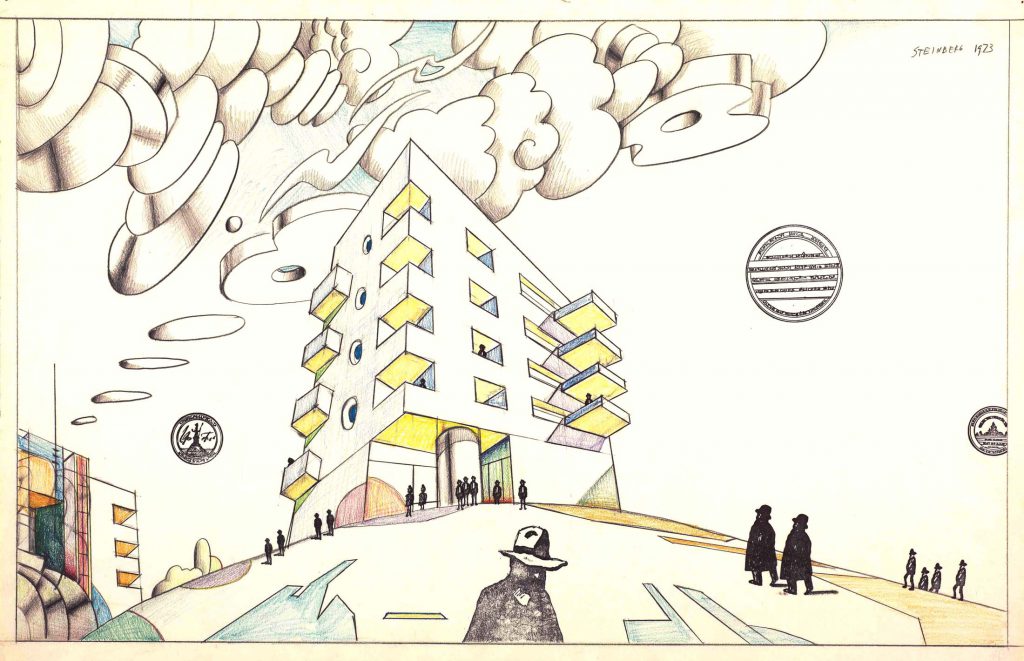

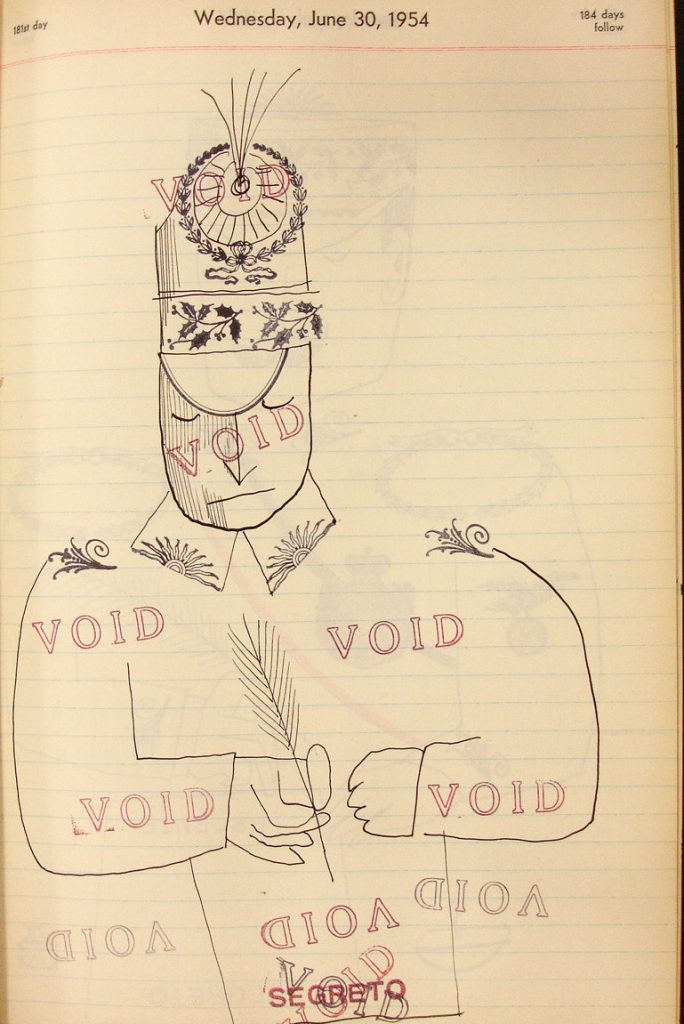

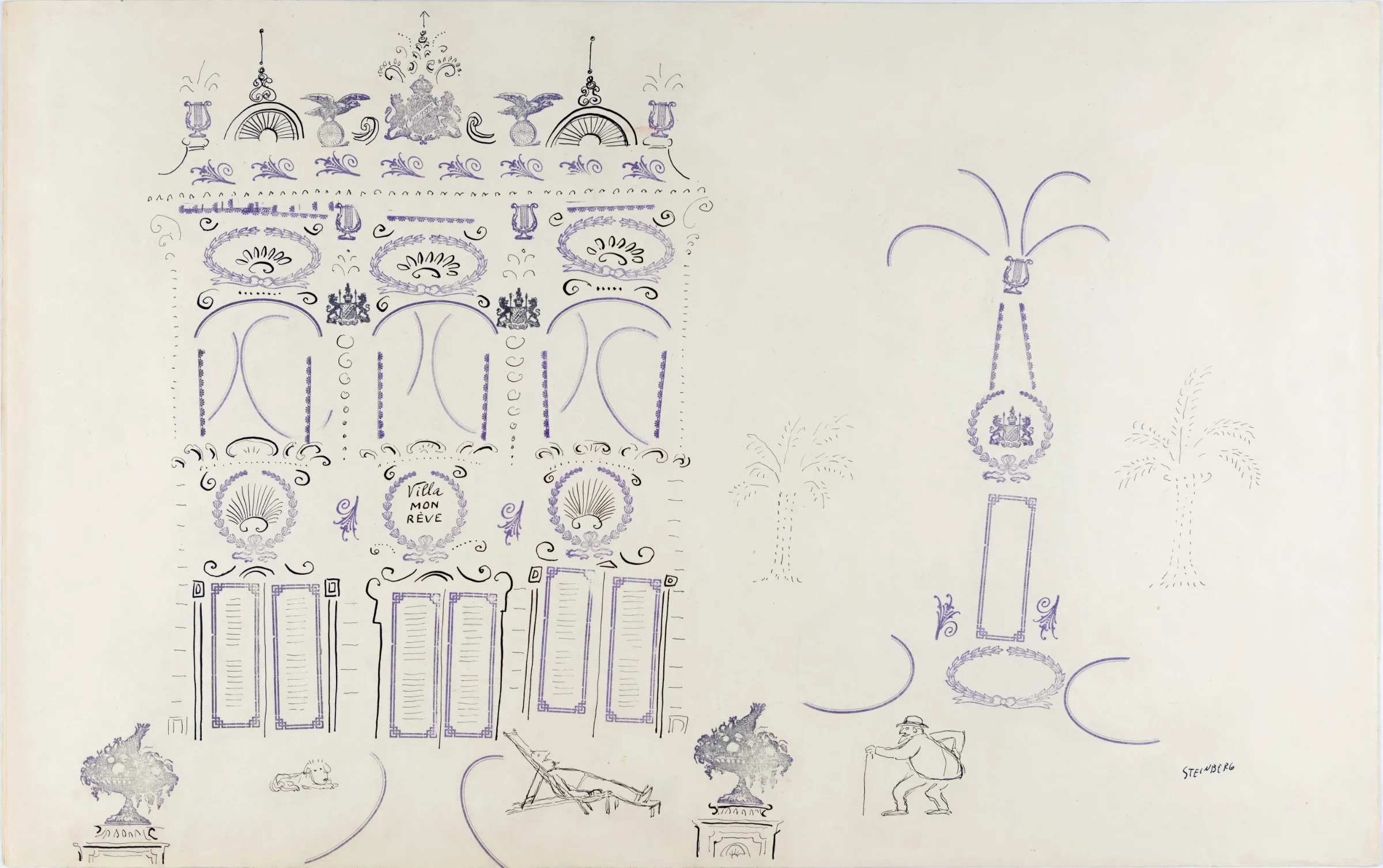

In 1966, however, Steinberg graduated to stamps made from his own designs and often used them to censure postwar society. Applied to compositions in other media or overtaking an entire sheet, the stamps serve to “parody the political and social world.”48

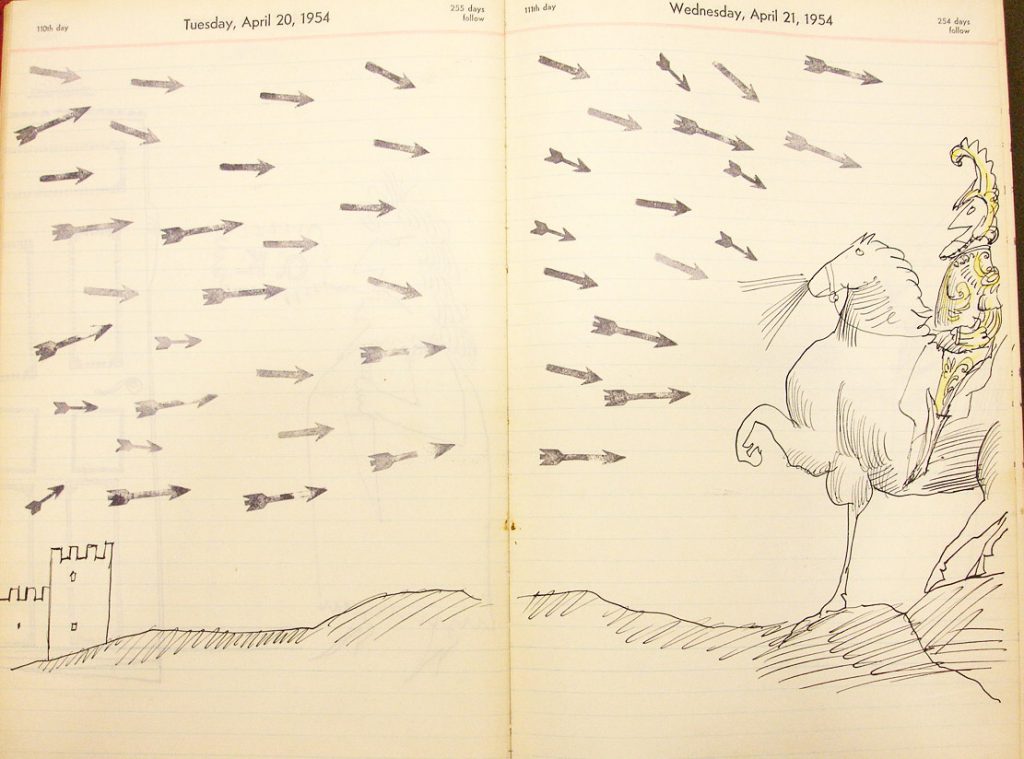

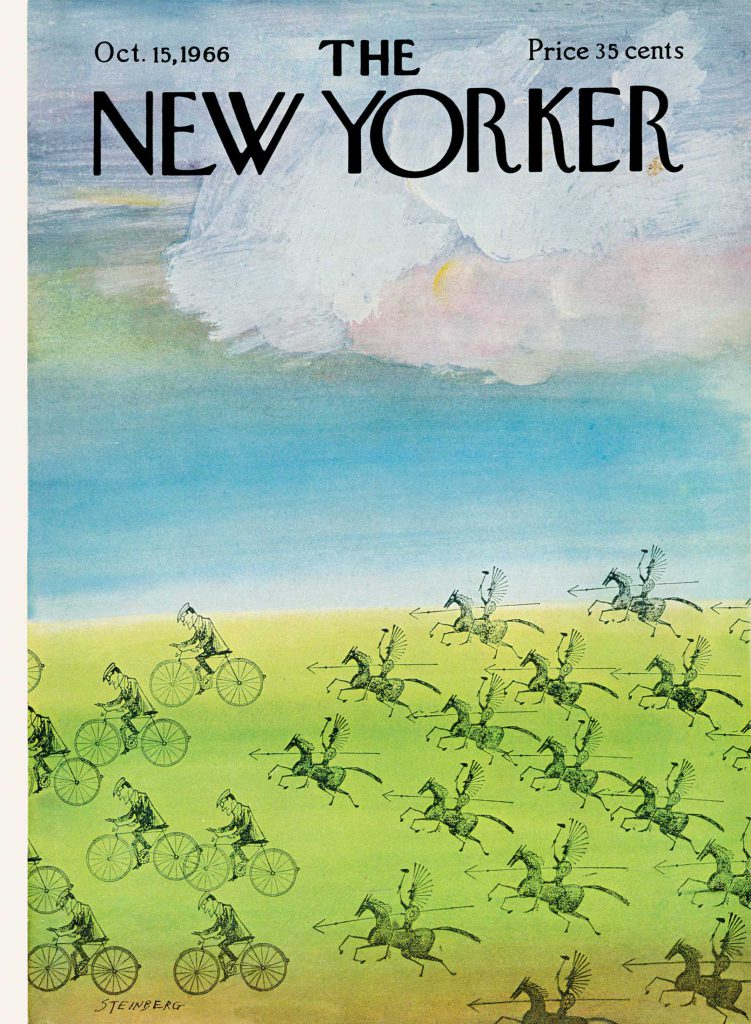

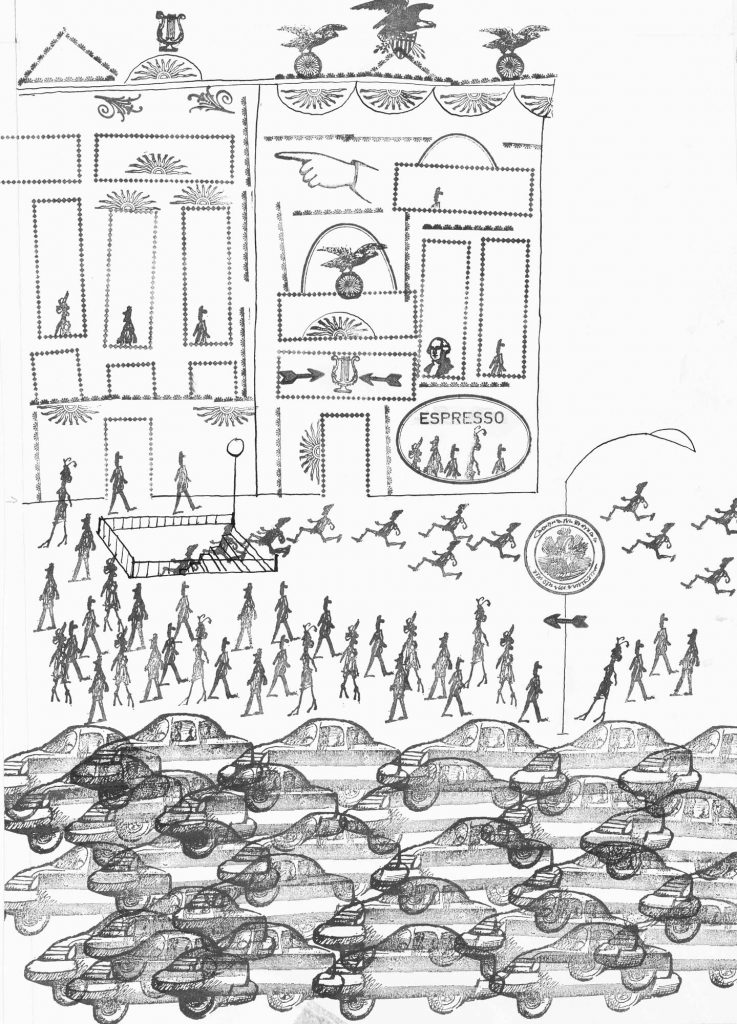

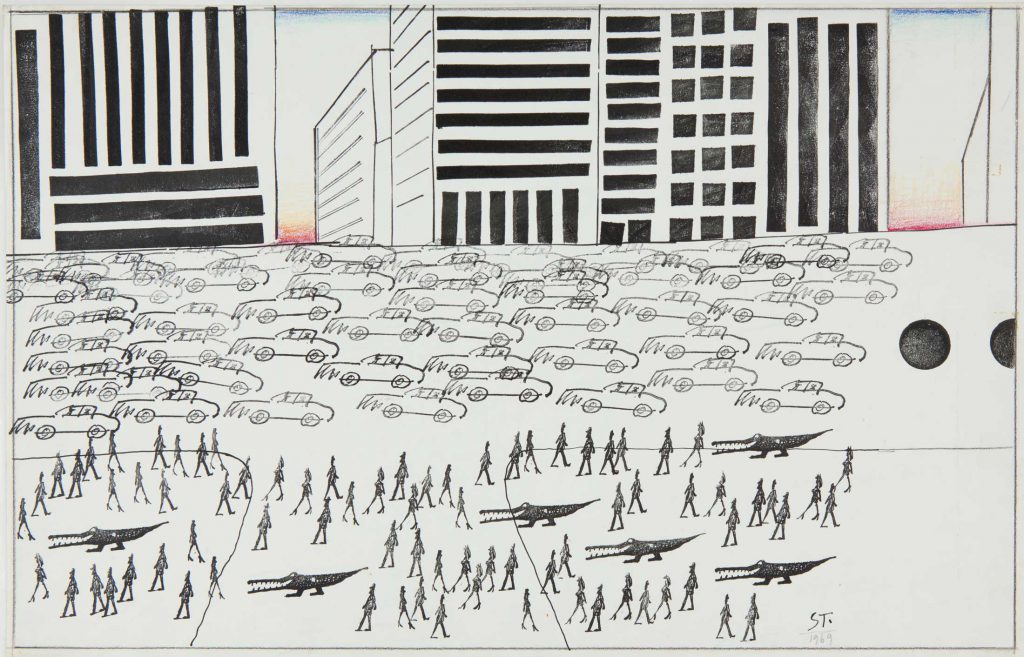

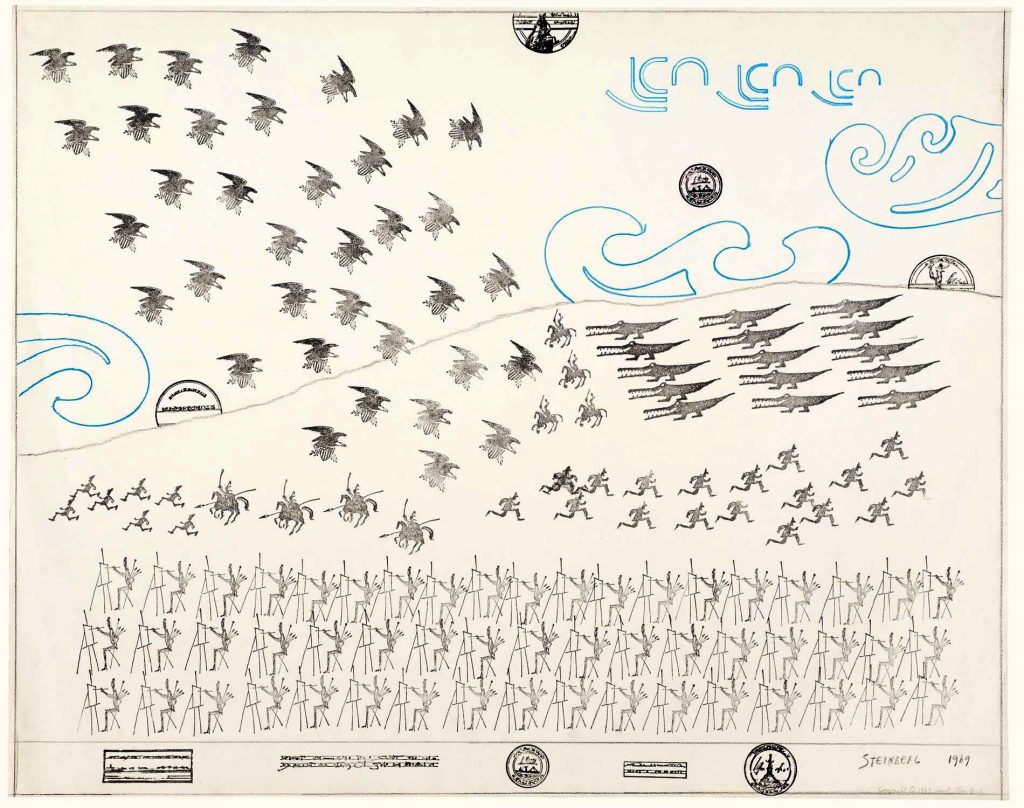

Dark standing men, artists at easels, crocodiles (Steinberg’s symbol for the dragon or danger), bicyclists, eagles, cars, Indians on horseback, marching and running men, no less than the elements of architecture—lines and rectangles.

All these, he said,

“I used like an alphabet. But instead of letters, I had at hand geometric figures with different horizontal or zigzag traits, silhouettes, crocodiles, pieces of wire mesh, and machines. All these stamps allowed me to render crowds, concentration camps, landscapes, Bauhaus architecture, military decorations, to build factories and all kinds of imaginary engines. With my stamps, I create series, as if my characters emerged from a computer, identical to each other, regimented the way they appear in our rigid society; in this way I destroy conventions more effectively than with drawing and painting.”49

Steinberg found rubber stamps an apt medium to express his outrage at the Vietnam War. “The cliché, the rubber stamp, has a political meaning,” he declared.50 Artists and War, Joel Smith observed, “condemns the war on specific grounds—it spells disaster for culture. As the vast war machine of eagles, crocodiles, and armed lancers carries out its clockwork atrocities, a corps of artists seated at their easels prepares to crank out protest art, their lockstep reaction mirroring that of an army.”51

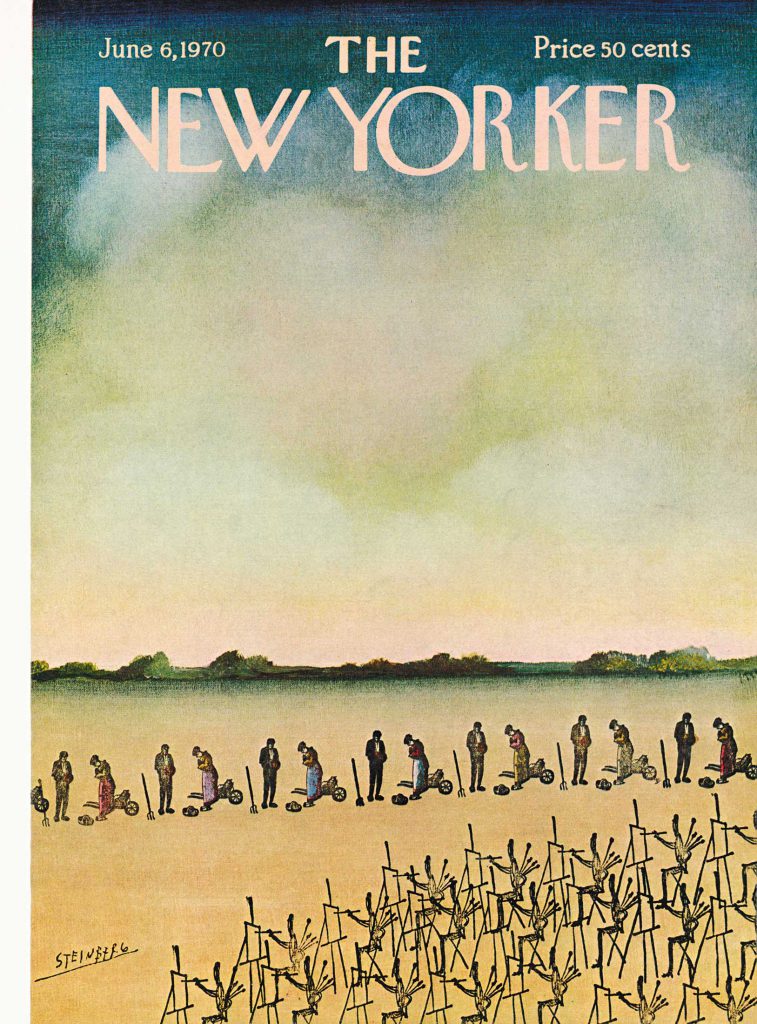

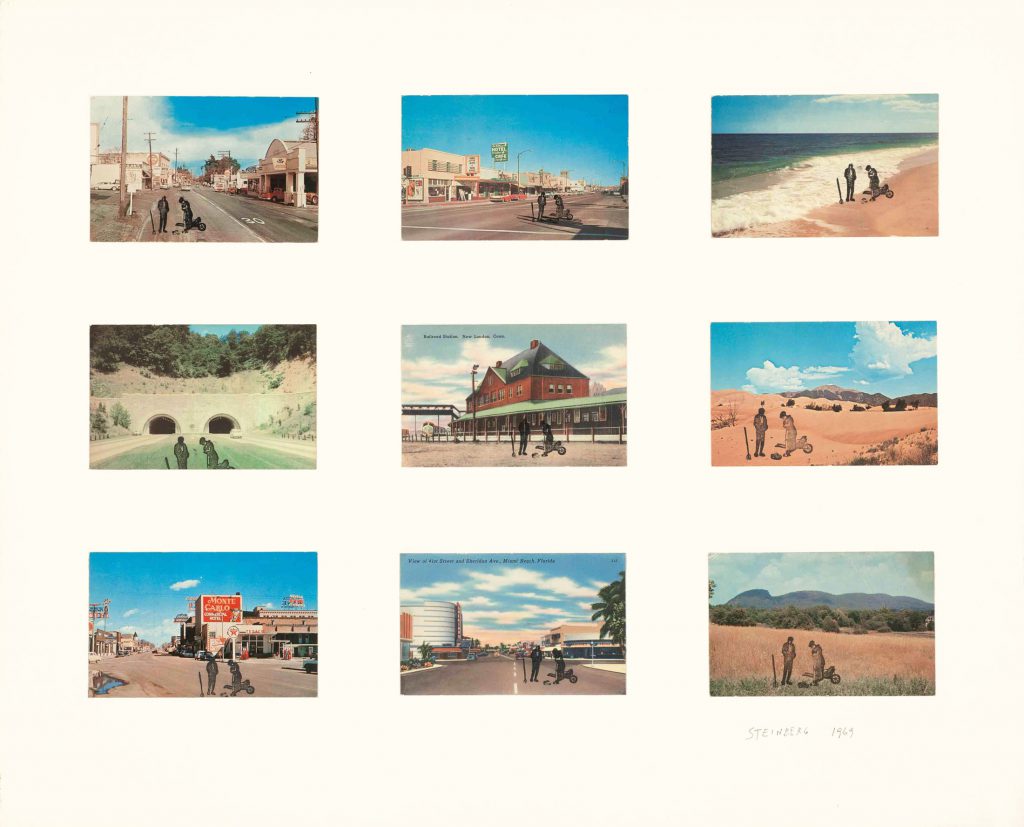

One work of art made repeated appearances in Steinberg’s rubber stamp roster: the pious peasants in Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus (1857-59), a painting he had known from childhood. His father’s boxmaking factory “produced boxes for chocolates, bonbons, and sugar-coated almonds—deluxe boxes on whose glossy covers was an artistic reproduction in chromolithography, the imitation or reproduction of an oil painting…Millet was ideal for chocolate boxes because he combined the classicism of the Renaissance with socialism, which at that time was not only popular but also virginal (no one yet knew of the horrors that might come, and did come).”52 In a 1970 New Yorker cover, a lineup of the Millet couple poses for a crowd of plein-air painters, a jab perhaps at the perceived conformity of the museum world. In Nine Postcards, the banal compositions and chromatic intensity of modern tourist postcards receive a visit from the more reverent 19th-century landscape tradition.

In Steinberg’s 1969 shows at the Parsons and Janis galleries in New York, as well as at the Galerie Maeght, Paris, rubber-stamp drawings predominated. Although they never again appeared in such concentration, stamped motifs, especially pseudo-seals masquerading as suns, thenceforth became pervasive in Steinberg’s art, and can be seen in many works on this site.