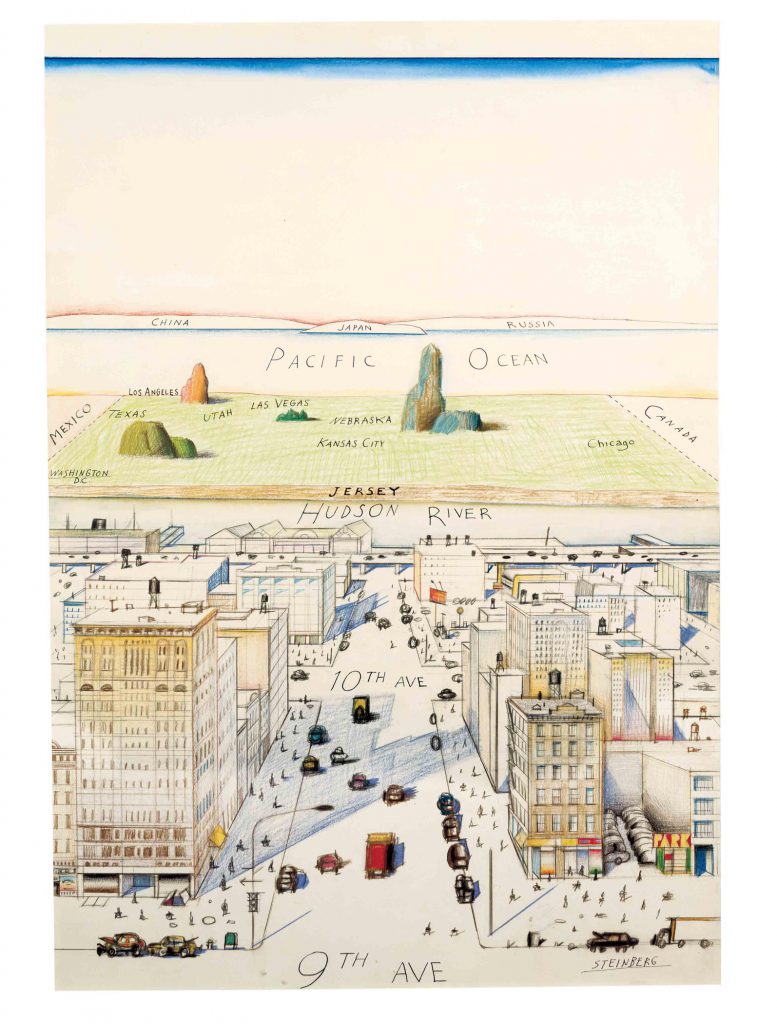

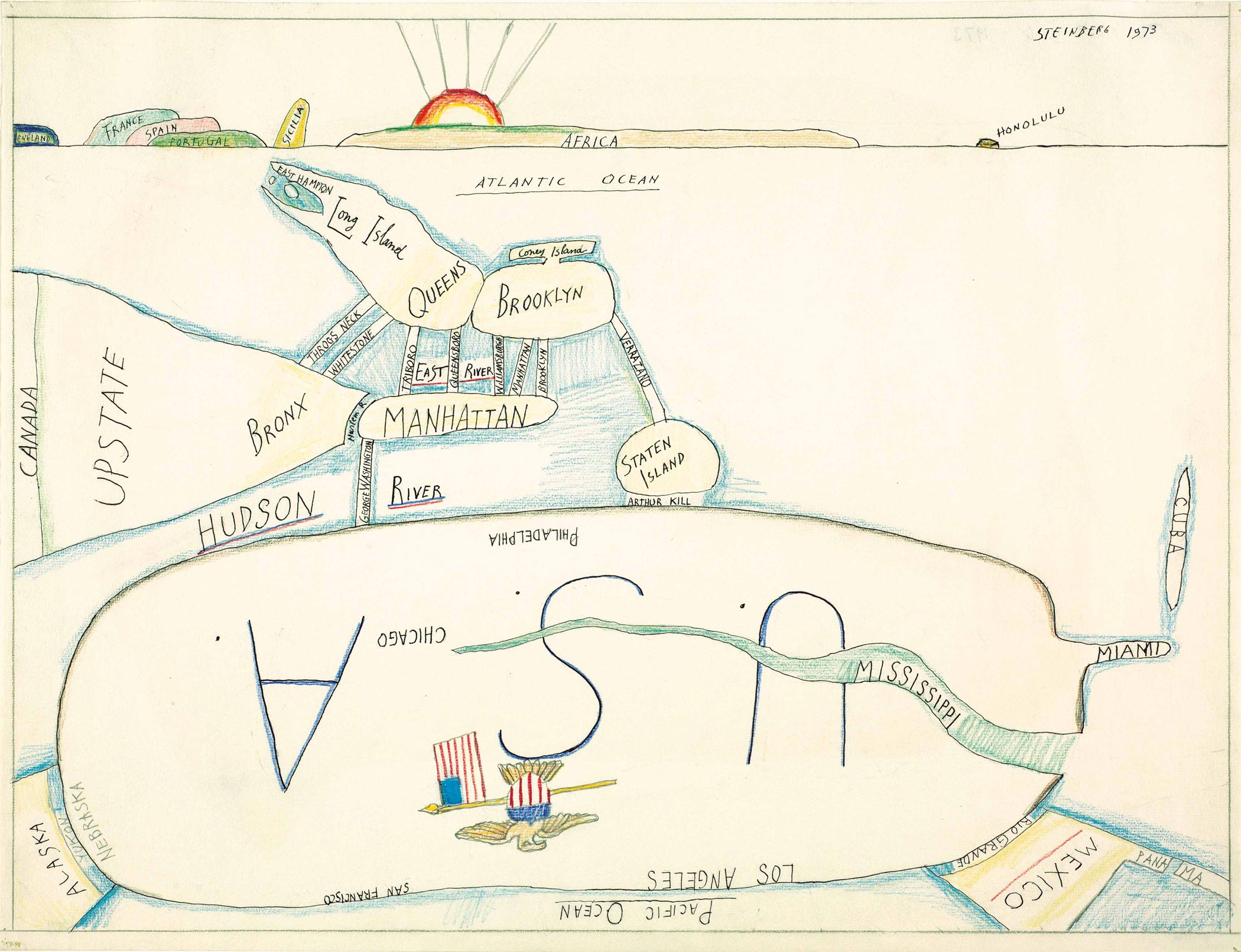

View of the World from 9th Avenue, the March 29, 1976 cover of The New Yorker, remains the drawing with which Steinberg is most closely associated in the public imagination.

A parody of Manhattanites’ provincial perception of life beyond the Hudson River, the cover—and the posters of it sold by the magazine—spawned countless imitations and pirated reproductions. Steinberg finally brought suit against one appropriator and won a large settlement.82 However, it was not copyright infringement alone that distressed him, but as well—and perhaps more—the exclusive identification of his art with that runaway image. Isolating View of the World from the rest of his oeuvre, you miss its larger significance: as one work within a parade of images that harness the graphic device of the map to visualize more than geography. The map for Steinberg is not a system of geographic measurement but a way of thinking.

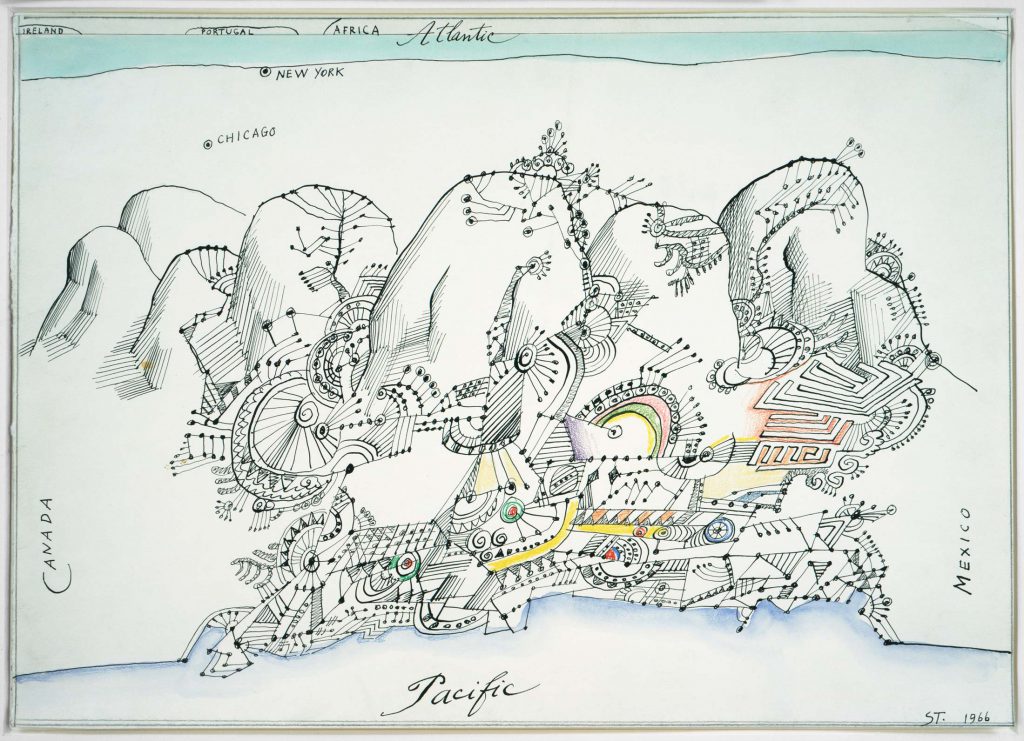

View of the World itself has forerunners and descendants, beginning with The West Coast.

This drawing of 1966 runs in the opposite direction, from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans, with the intervening continent rendered as a schematized urban layout of Los Angeles backed by a mountainous terrain, the whole drawn in Steinberg’s “doodle” style—the quasi-geometric designs that filled his appointment books and notepads and then migrated to his art as yet another found style for his repertory.

Seven years later, The West Side again followed a west-east direction, but from a Manhattanite’s perspective, where the US looks like an outsized suburb of the five boroughs.83

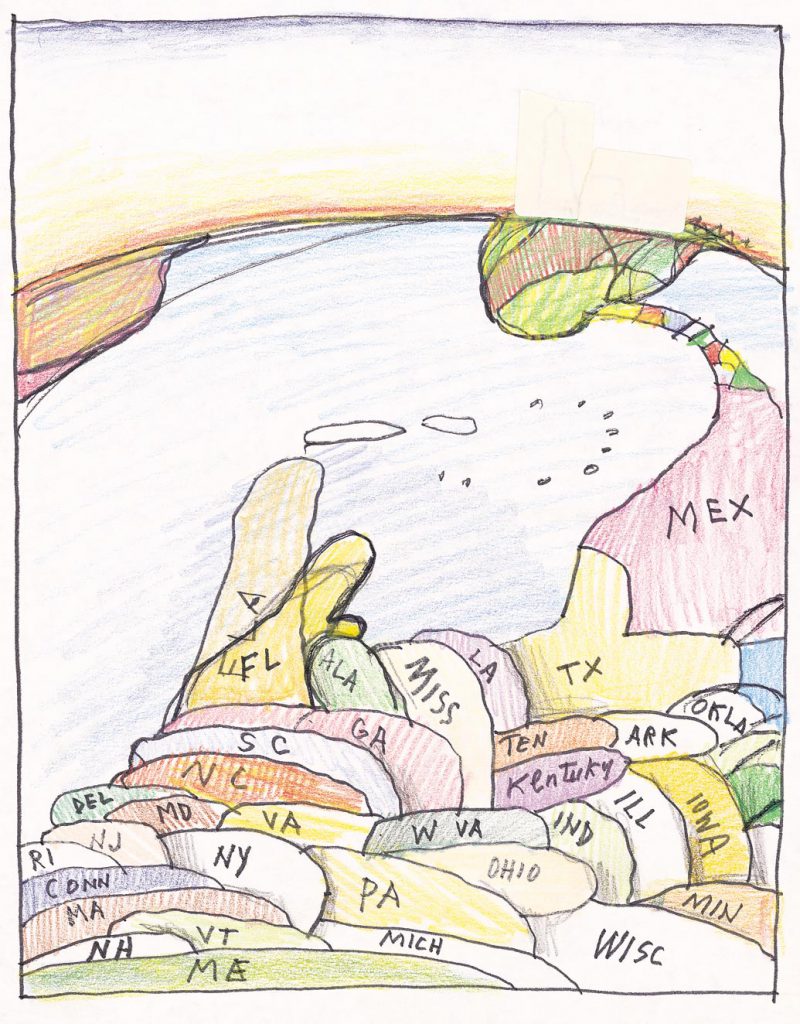

In the later 1980s, Steinberg made a 90-degree turn in a series of drawings that take a bird’s-eye view of North America, Mexico, and sometimes the northern tip of South America, with the US states (almost but not quite accurately placed) presented as a series of overlapping, cascading hillocks descending progressively southward.

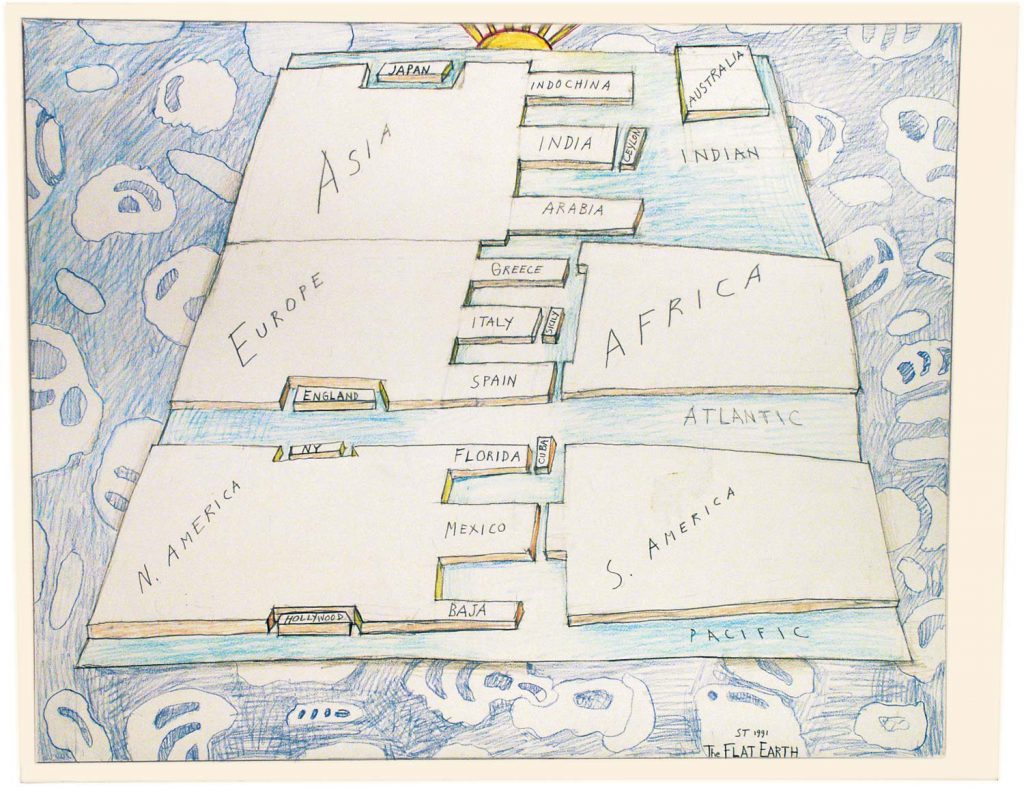

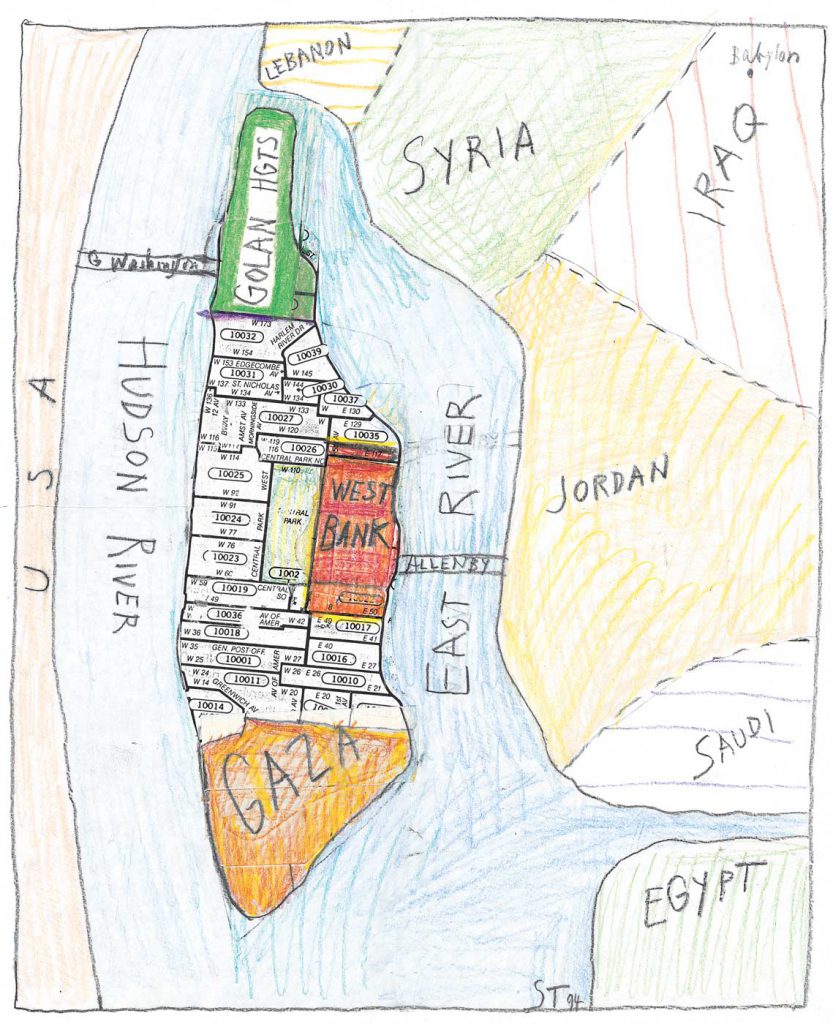

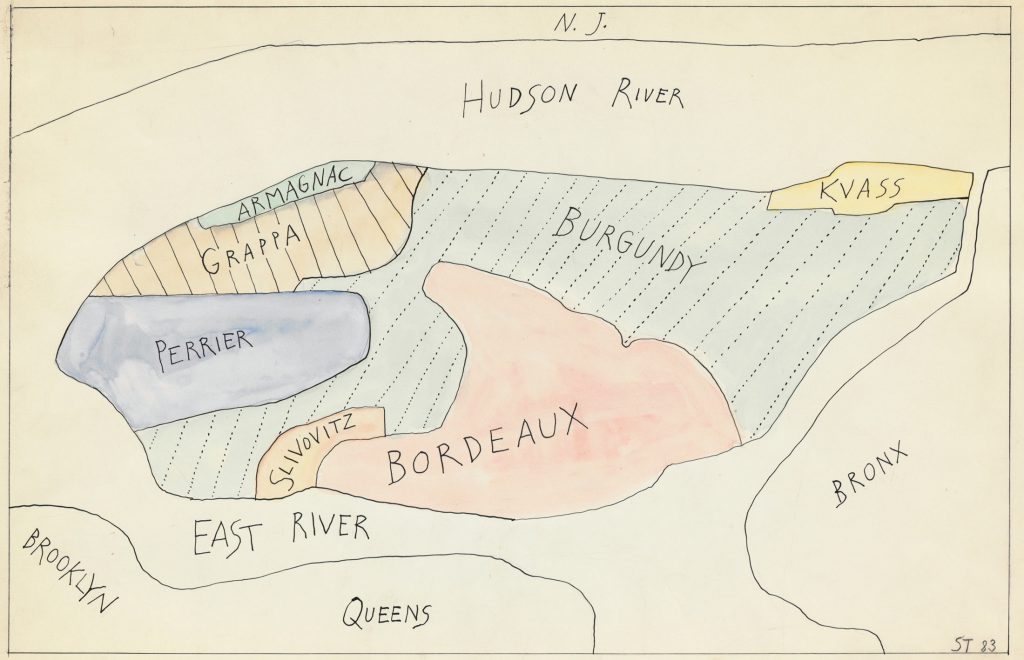

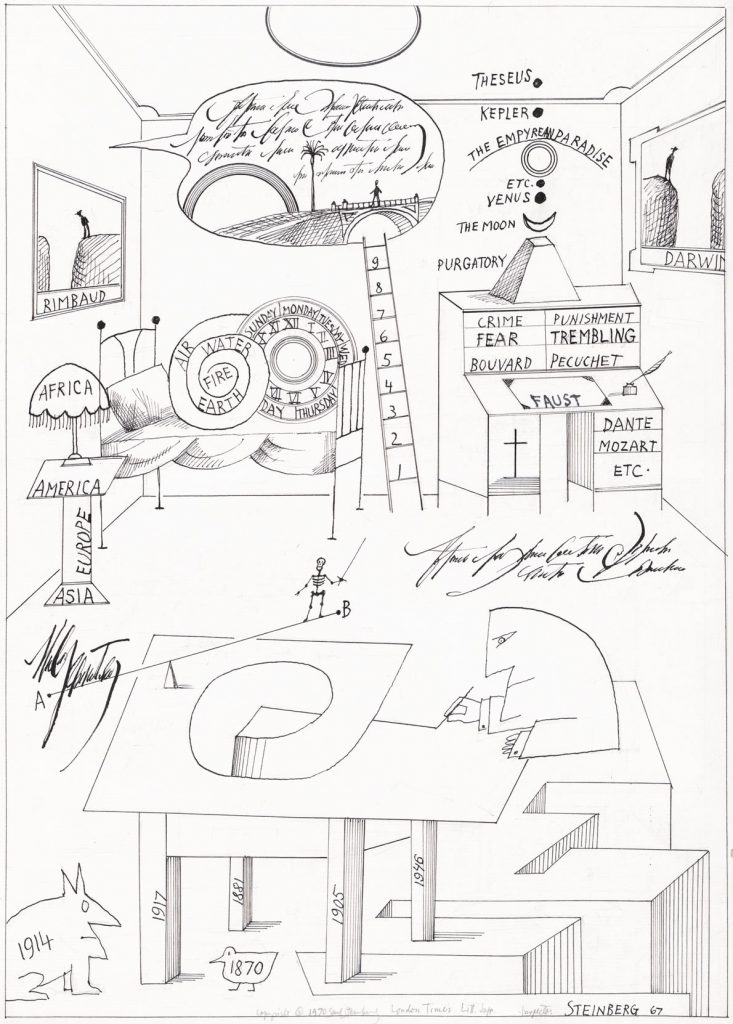

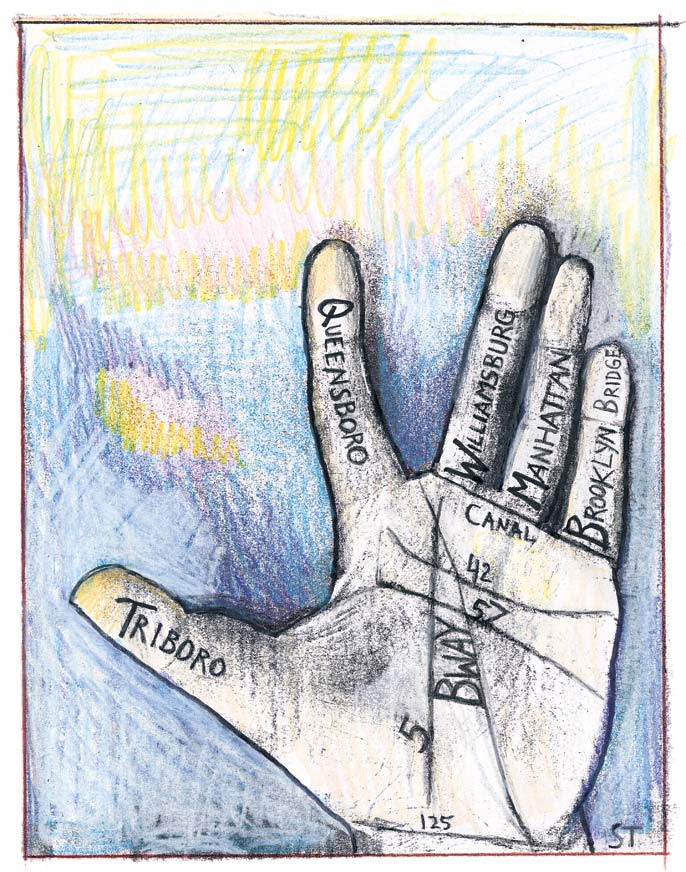

Cartography could be parodied too: the globe flattened by geometry under the rule of the sun or the chaos of the unknown; a Manhattan zip code map reborn as zones of Middle East conflict, or Manhattan neighborhoods sociologically determined by wine preferences.

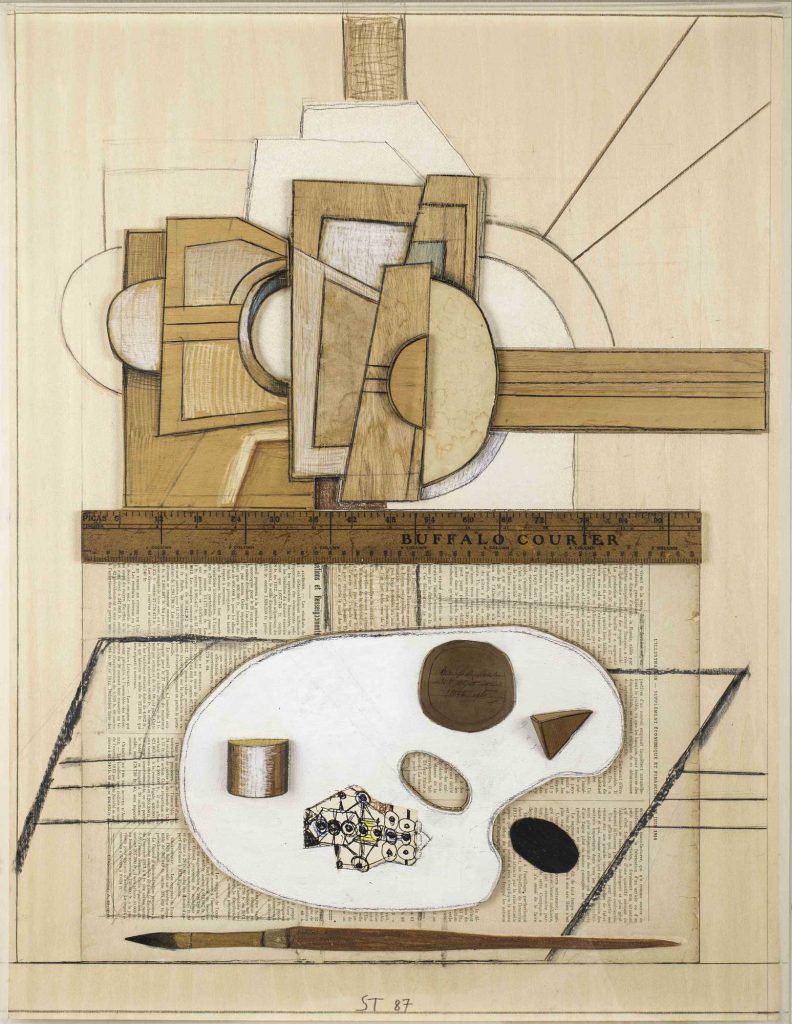

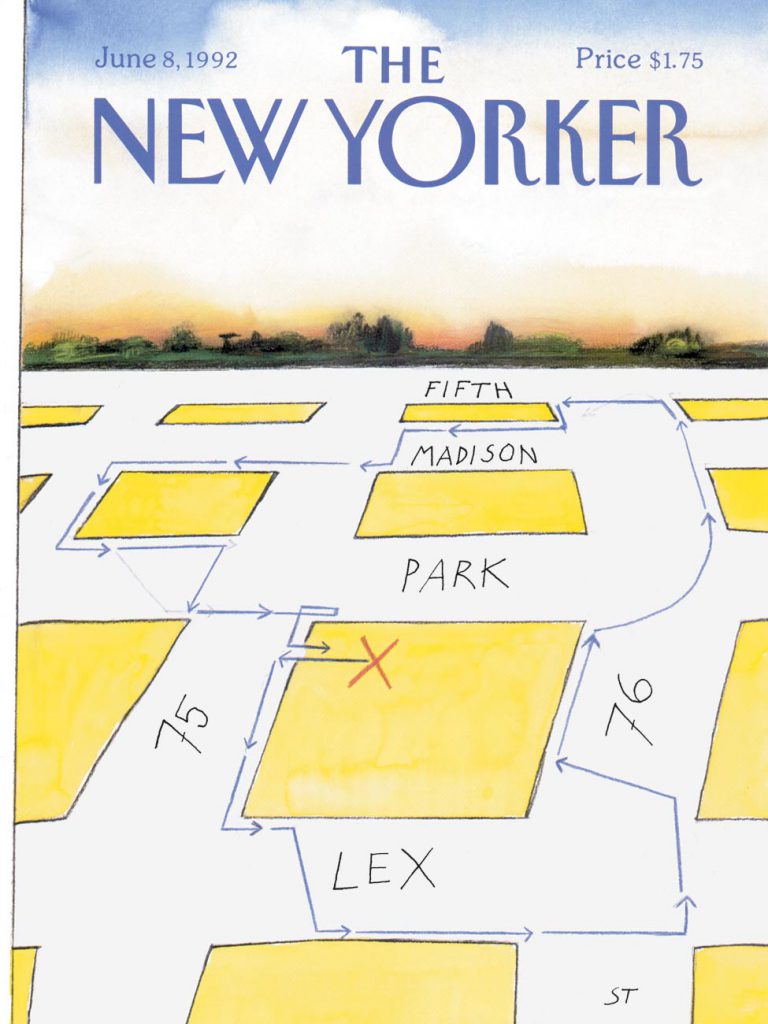

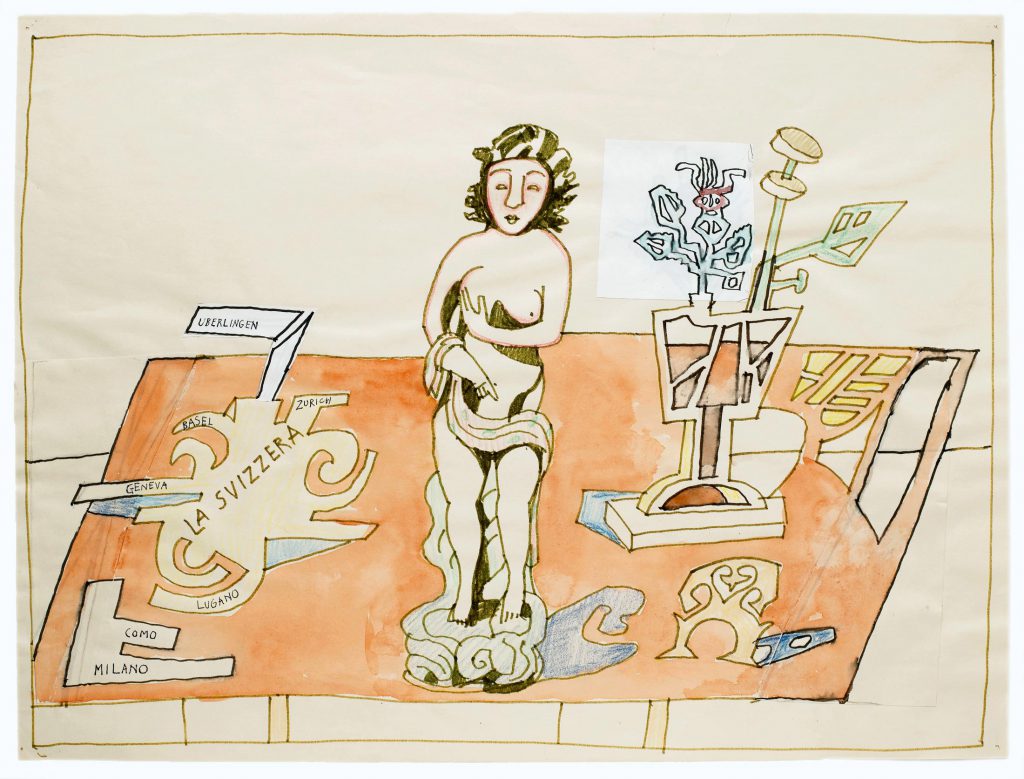

Maps also served Steinberg as autobiographical expedients: a street grid locating his New York apartment on 75th Street between Park and Lexington avenues; lying on a still-life table, a free-form map of Italy and Switzerland ending with “Überlingen,” the small town on Lake Constance where he regularly checked himself into a private clinic for physical recuperation.84

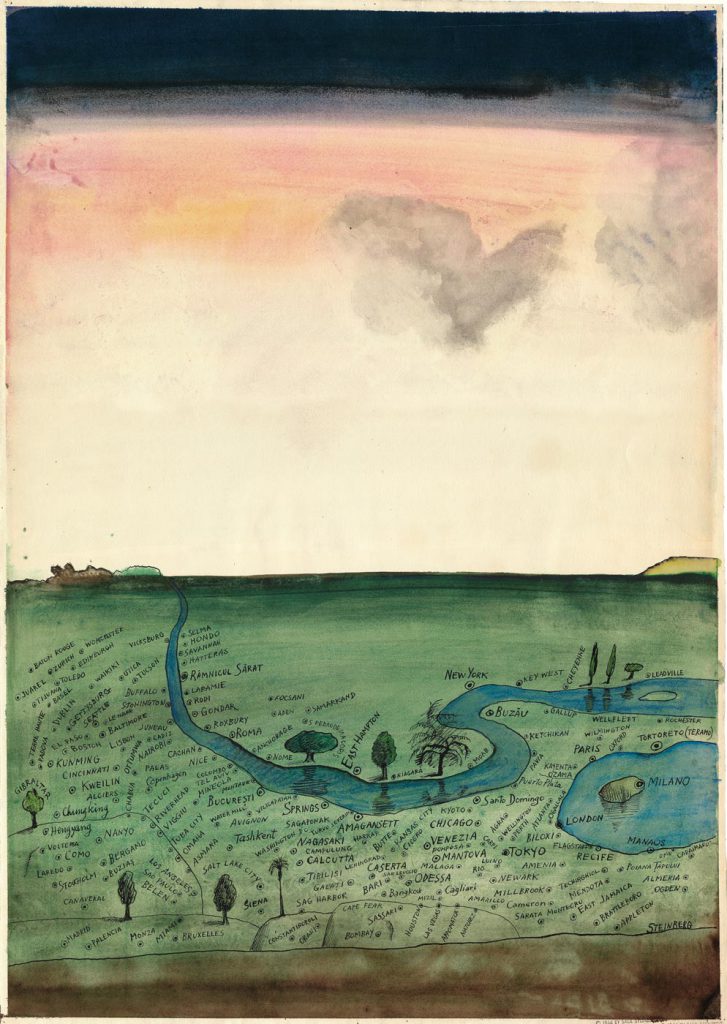

The large 1966 drawing that Steinberg titled Autogeography is a hybrid landscape-map.

“Over a plain meanders the river of Steinberg’s life, weaving among dozens of place names sized and sited according to the vagaries of fond or bitter memory: Râmnicu Sărat (‘a place invented for me to be born in’); Tashkent and Tuba City (‘where I bought a hat’), Riverhead and Calcutta, Milan and New York. Here, as so often in a career spanning six decades, Steinberg used a language of his own devising to recreate the world in his own image.”85

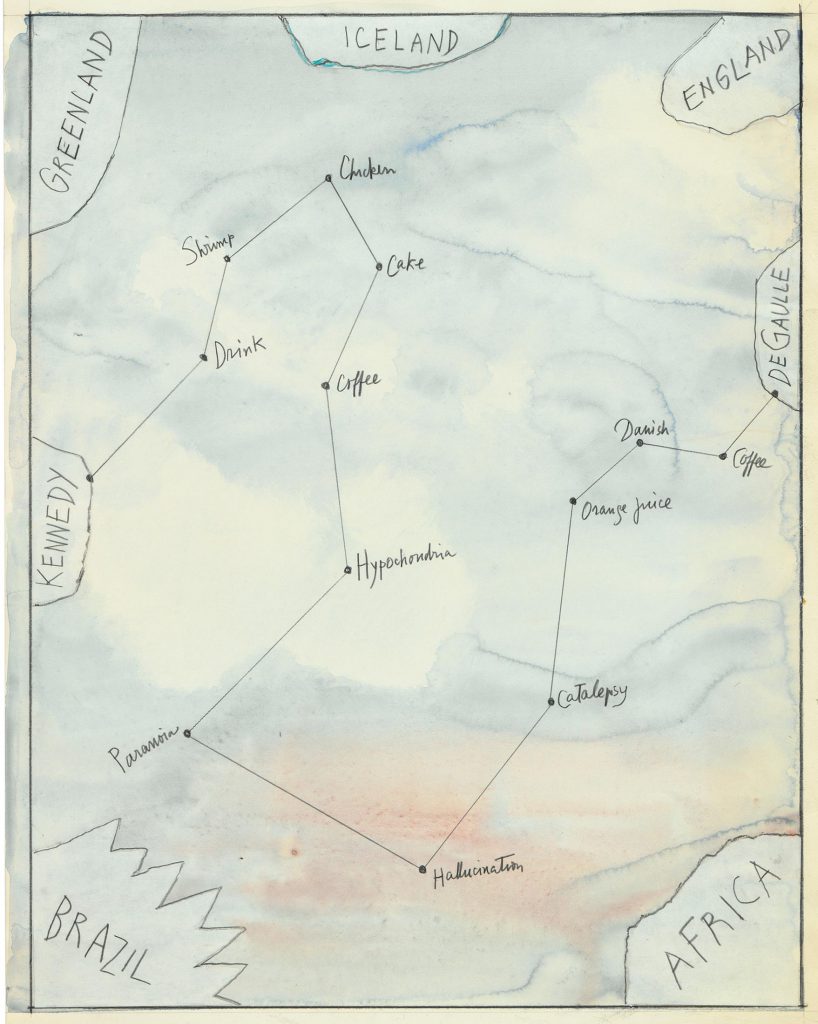

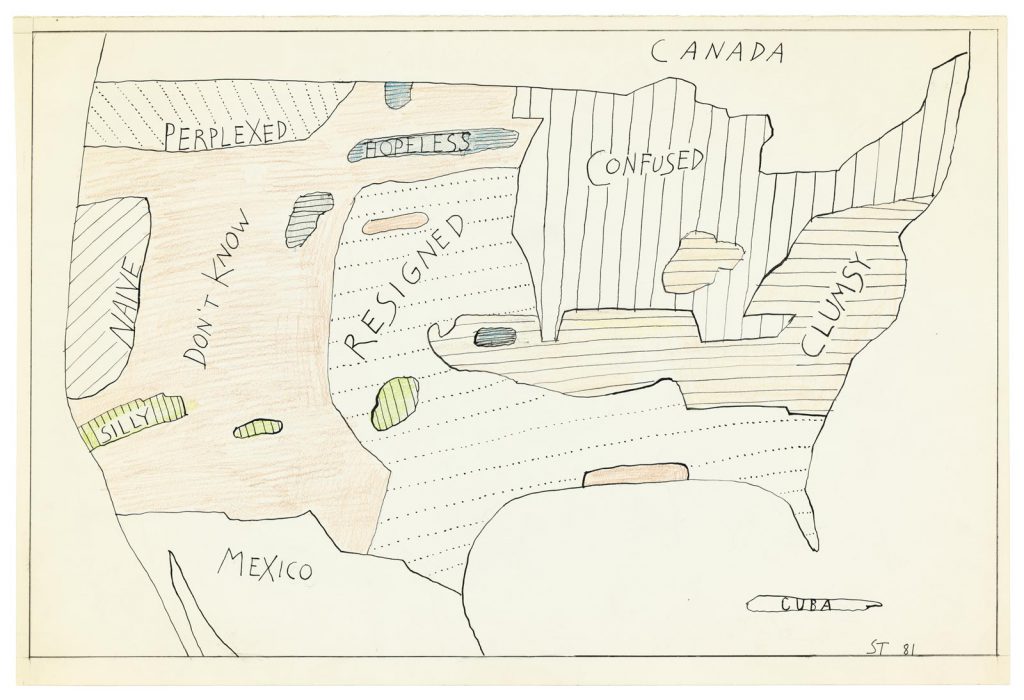

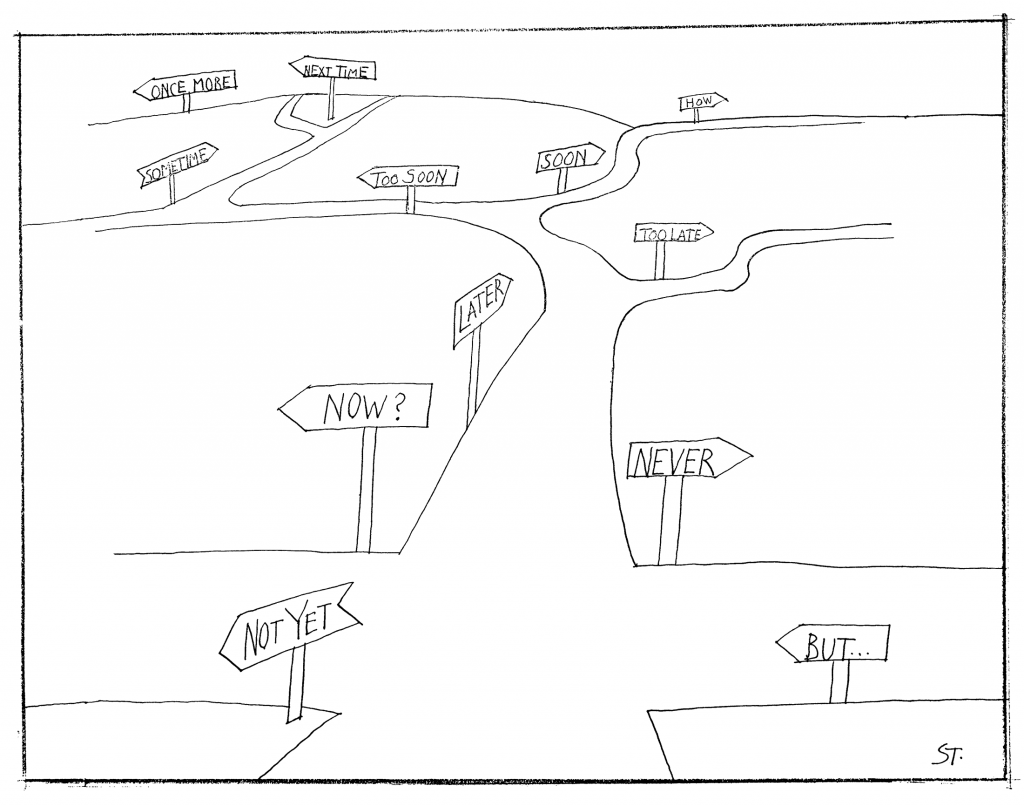

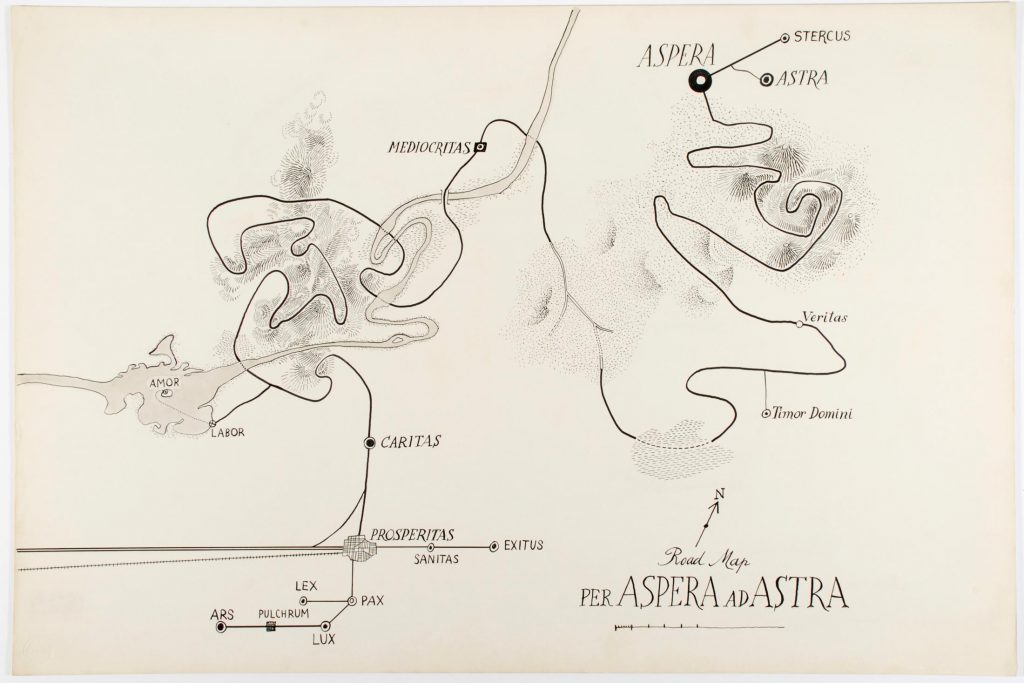

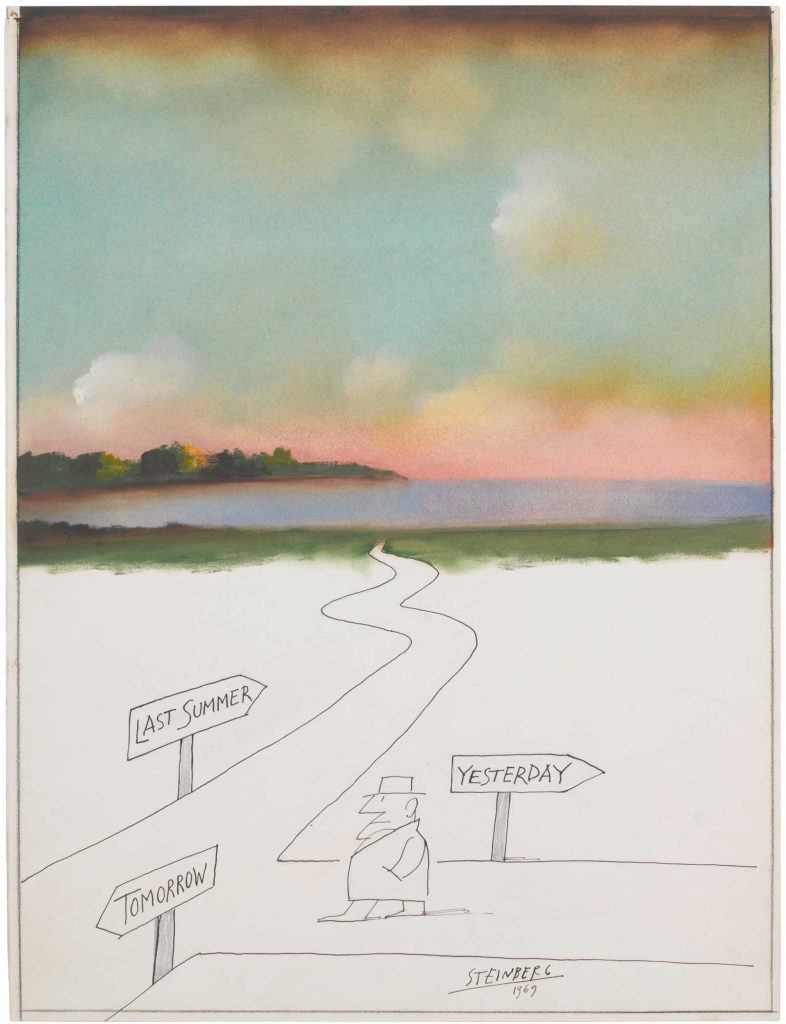

Among other cartographic inventions are maps charting emotional states or marked by angst-ridden road signs and rivers of aspiration.

Language and speech can also be mapped as culturally determined: in 1963, the map form became a dialogue between a sophisticated Paris femme and a Sardinian contadina, who compare their lives in the form of talk-balloon maps, the Parisian speaking of man-made boulevards and stylish side streets, the Sardinian a sparsely populated island.

![<em>Untitled [Paris-Sardinia]</em>, 1963. Ink, ballpoint, crayon, watercolor colored pencil, and pencil on paper, 23 1/8 x 14 3/8 in. The Art Institute of Chicago; Gift of The Saul Steinberg Foundation.](https://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/372.-C-045-SSF-7163-642x1024.jpg)

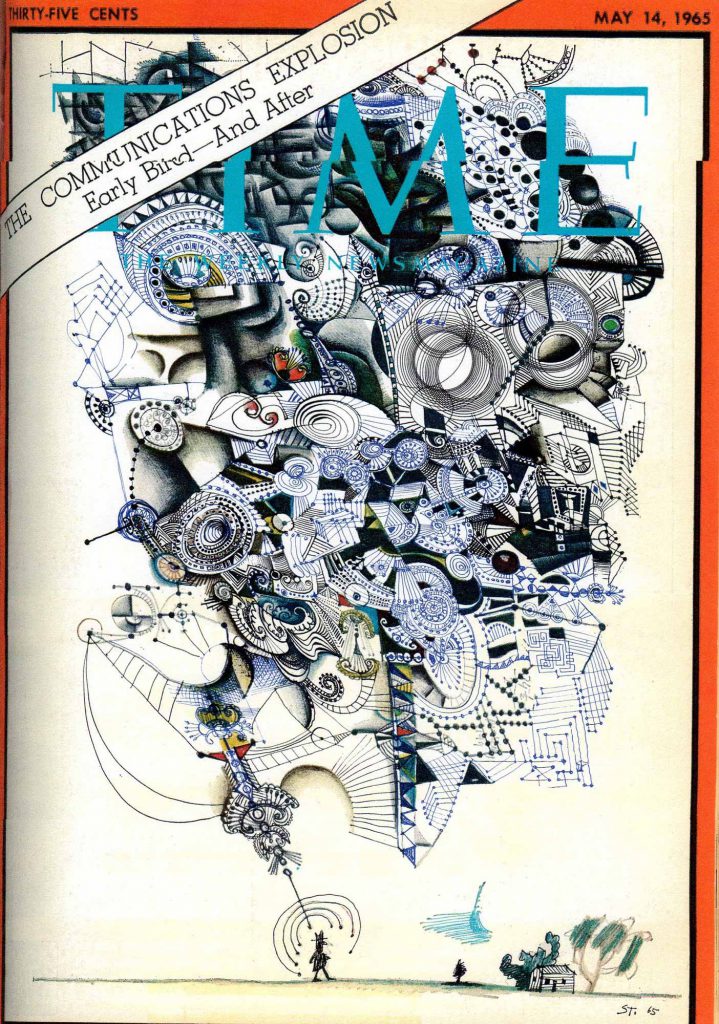

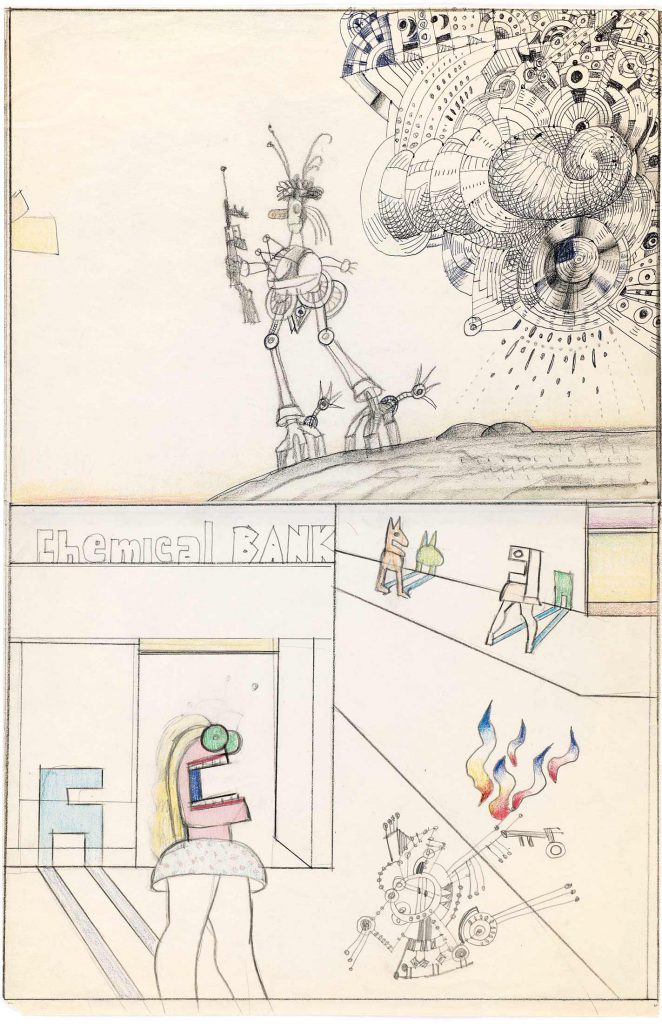

Elsewhere, the acronyms and initials that dominate American life cover a land- and skyscape, filled with wily groupings of commercial and political entities.

![<em>Untitled [Initials]</em>, 1964. Variant of <em>The New Yorker</em> cover, December 5, 1964. Crayon, pencil, and ink over pencil on paper, 19 ¾ x 14 ½ in. The Saul Steinberg Foundation.](https://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/373.-C-047-sm-SSF-916-64-749x1024.jpg)

The three lines of the New York City subway system (BMT, IRT, IND) meander, appropriately, through an underground tunnel, but so, in another tunnel, do the CIA and the MVD, its Russian counterpart. Broadcast networks occupy the lower sky, the sun is surrounded by airlines; at top, a Steinbergian pairing of the SAC, the now-defunct Strategic Air Command, and just above it, LSD. It’s a crafty coupling of American air power and hallucinogens whose implications we are left to ponder.

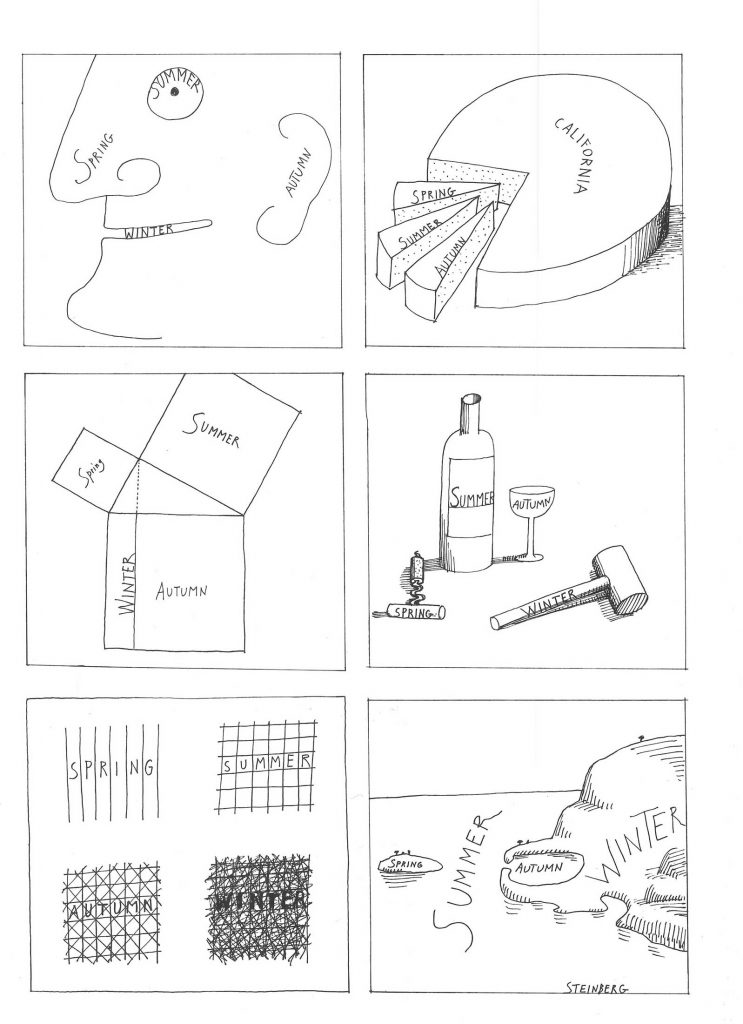

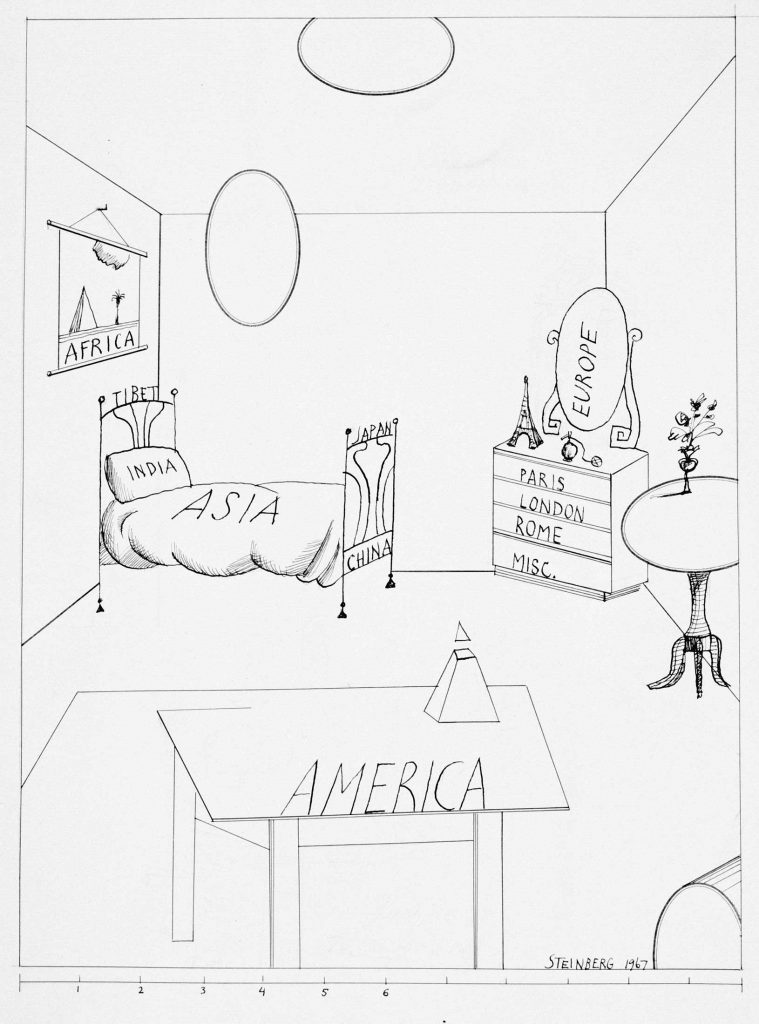

And if maps can service a world beyond cartography, then things in that world—people, furniture, body parts, and even a wheel of cheese—can play the part of maps.

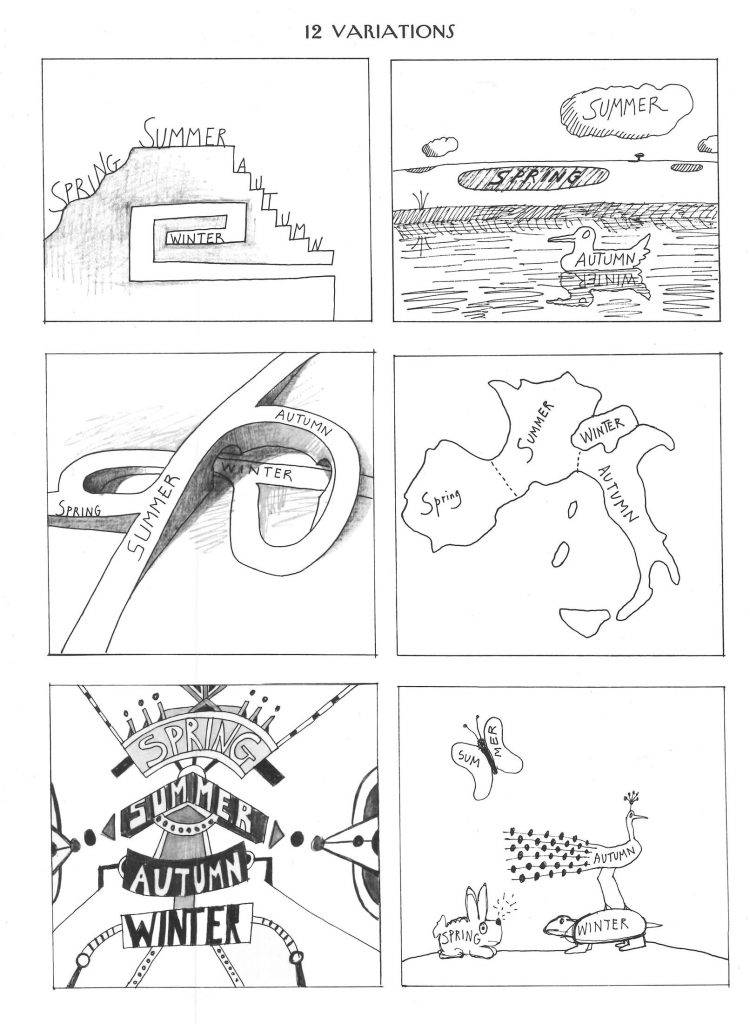

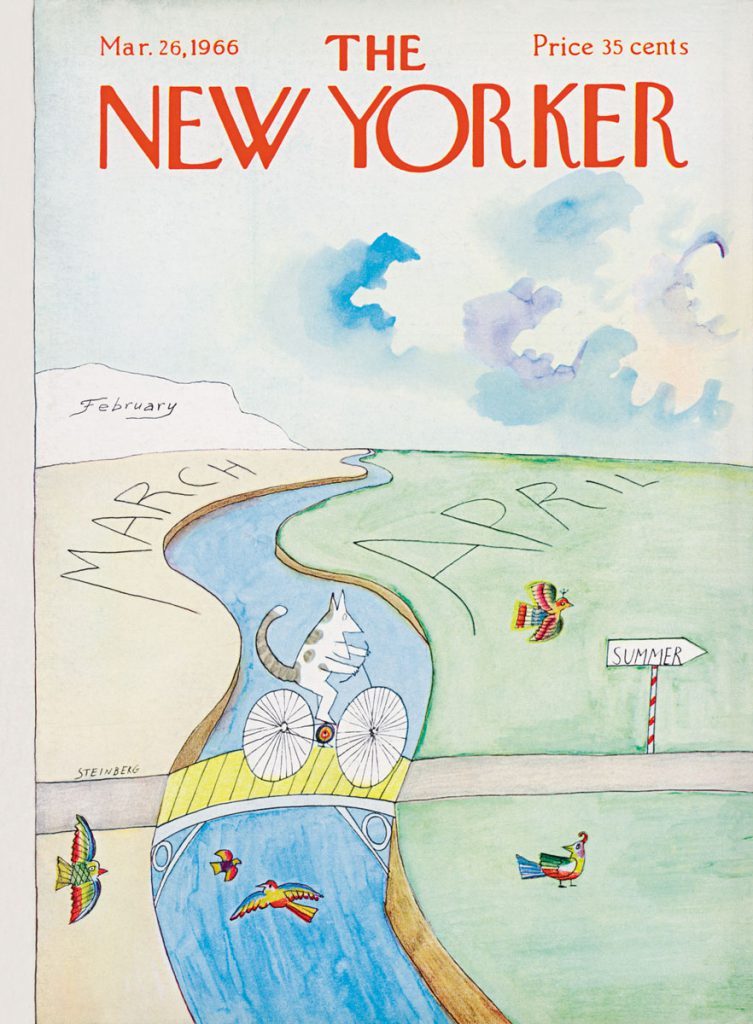

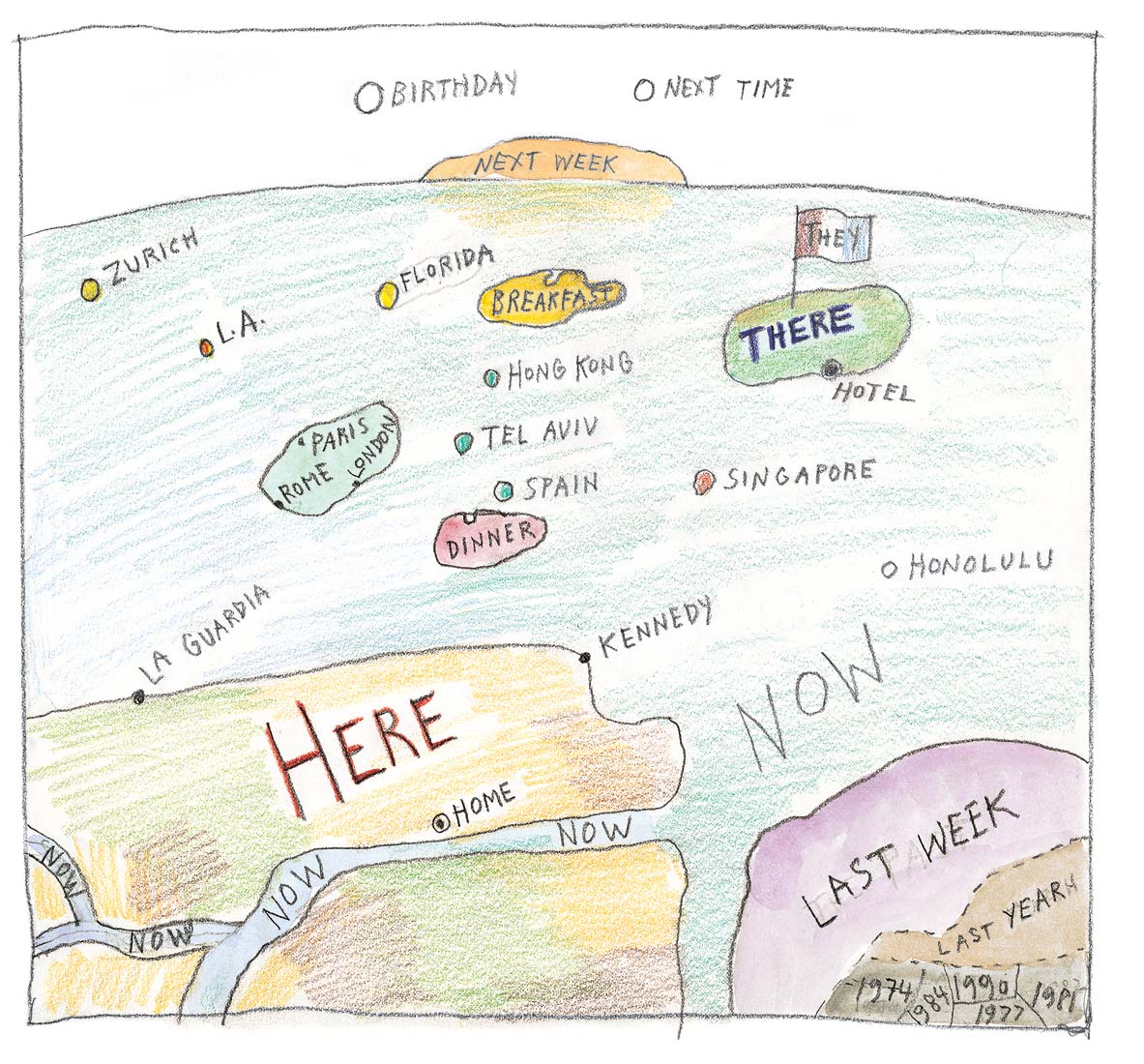

Time too is amenable to mapping. Road maps take us from one month or season to the next.

An on-high view of an air route wings from Last Week to the Here and Now; There is arrival, Next Week the future.

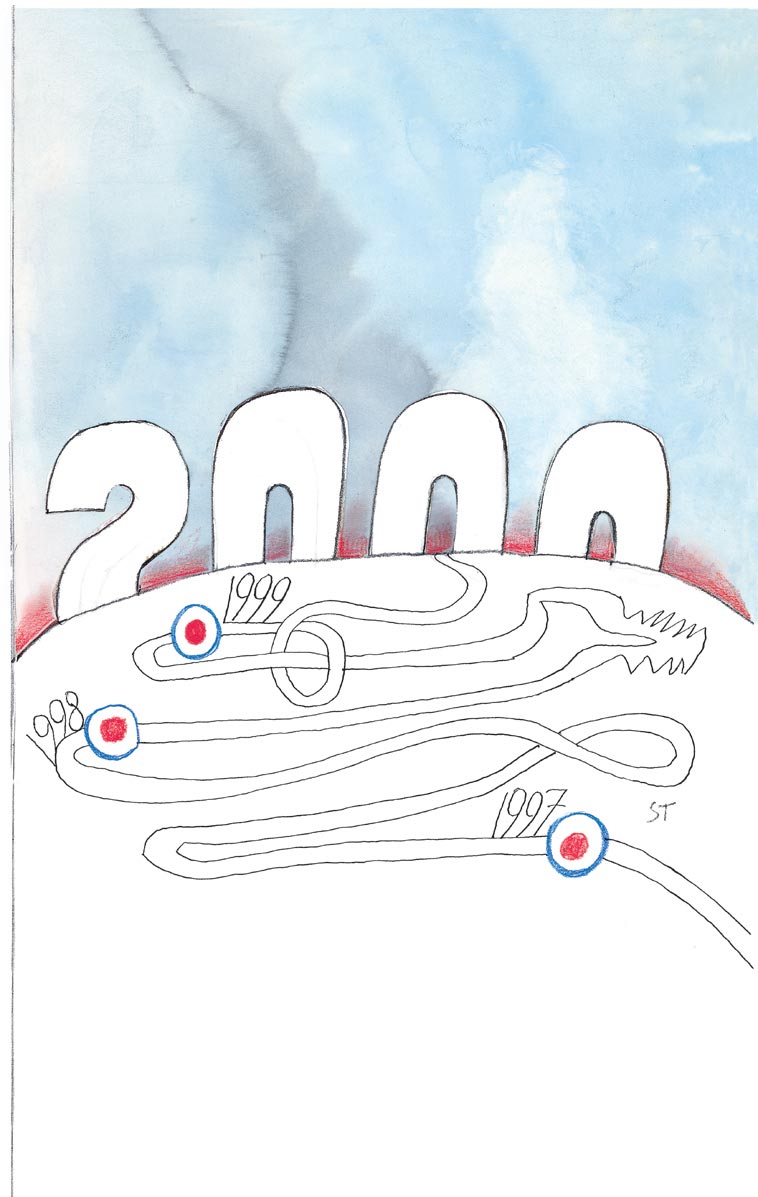

The most poignant of Steinberg’s time-maps is the one he produced for a New Yorker cover in 1997, just as Year 2K anxieties were getting under way.

The contorted route from 1997 to 2000 makes for a laborious climb up the hill, suggesting the eighty-three-year-old artist’s doubt about whether he would make it (he didn’t).

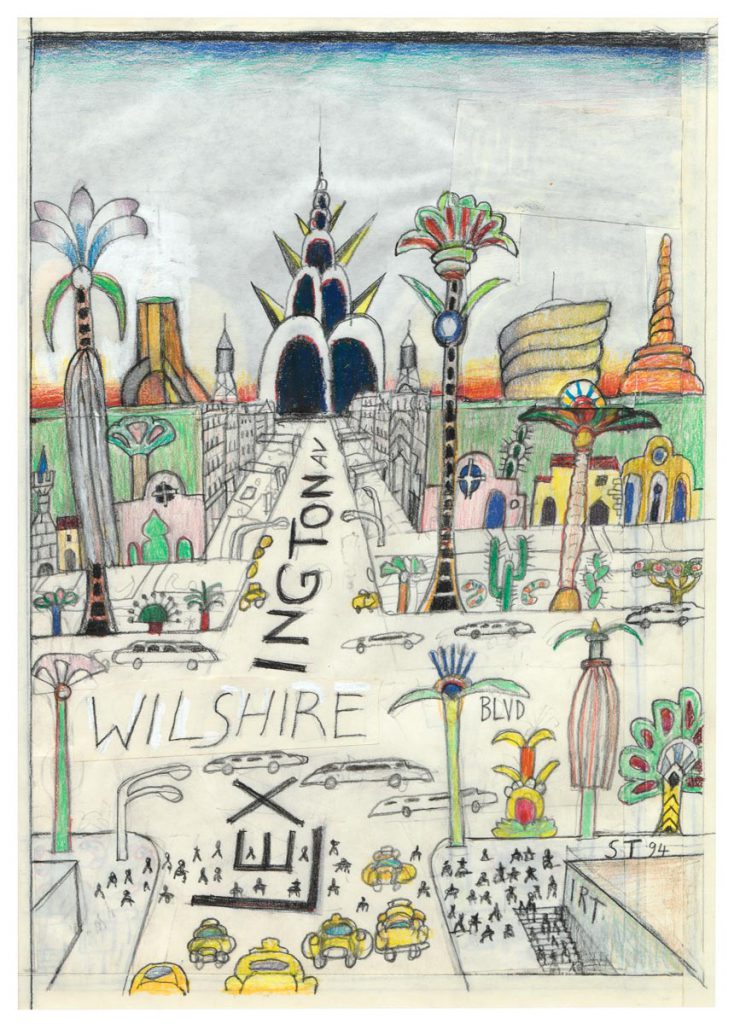

In 1994, Steinberg revisited that pesky 1976 New Yorker cover in a new cover that again explored the idea of the world seen from a provincial perspective.

“In Wilshire & Lex, the boulevards of Los Angeles and Manhattan intersect. Here the planet is shrunk not by local chauvinism but by the corrupting influence of New York money and Hollywood dreams. Ultimately, Steinberg regarded citizens of the twentieth century as ‘victims of an immense prank, which has lasted perhaps since the year of my birth, 1914.’”86