Sections

1990

In the early 1990s, begins to add color to some of his black-and-white ink drawings of the 1940s and 1950s.

February 23, dinner with Saul Bellow, “a rare friendship with a man of my own age and caliber, and I blossom in his company.”

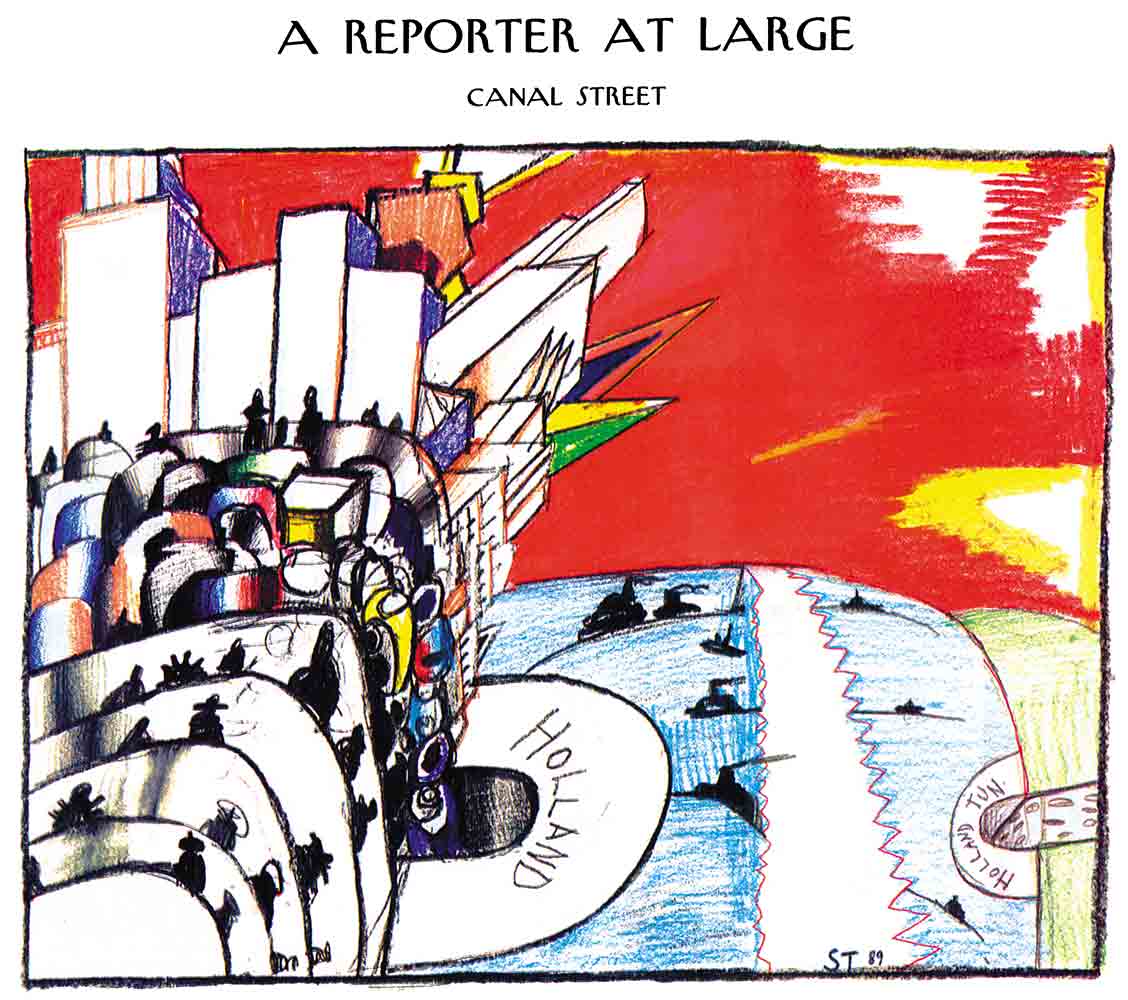

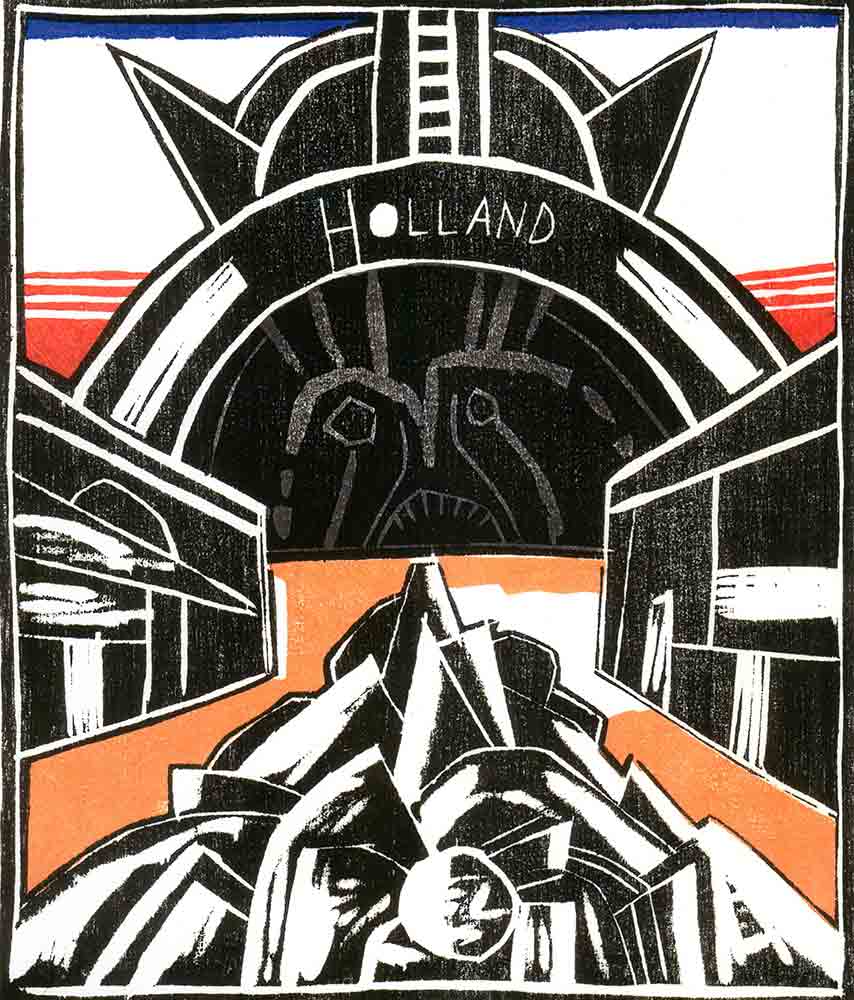

Canal Street, a limited edition book with text by Ian Frazier, published by the Library Fellows of the Whitney Museum of American Art. The book contains woodcuts and lithographs with ST’s take on the congested entrance to the Holland Tunnel from Canal Street in lower Manhattan. An excerpt from Frazier’s essay is published in The New Yorker in April, accompanied by a Steinberg drawing—his first in the magazine in more than two years, and the first time his inside drawings appear in color.

1991

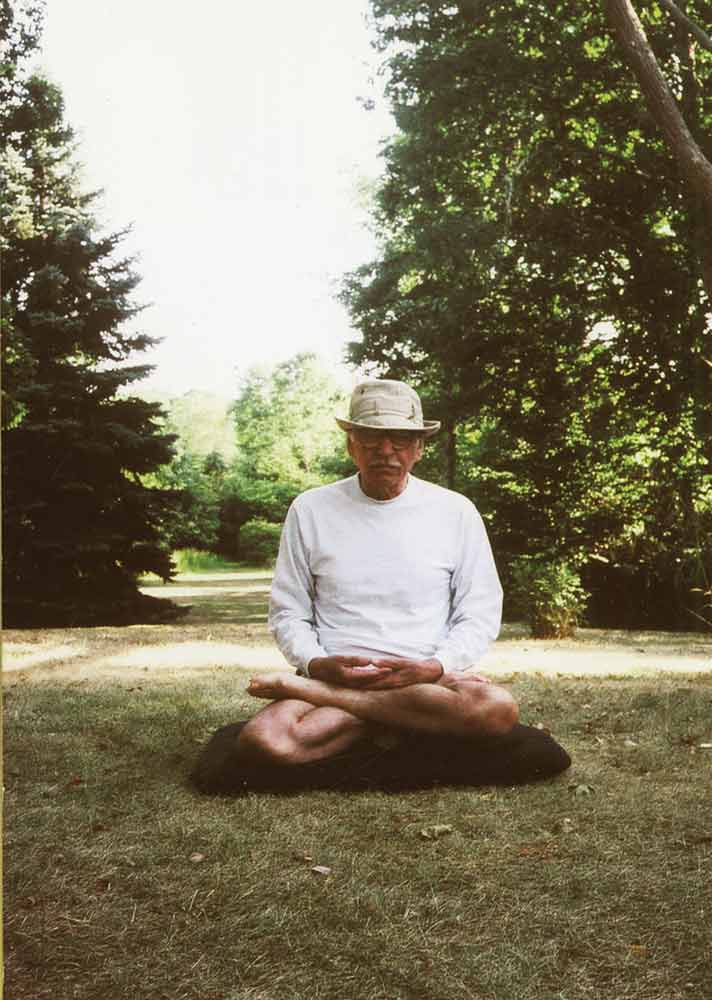

Increasingly suffers from bouts of depression, for which he turns to Zen meditation: “These days,” he tells Buzzi, “I sit Zen style, and I also read in order to understand or—as the gurus prefer to put it—in order not to understand. I’ve already been sitting this way for years, for the sheer pleasure of it, but now perhaps I’m beginning to not understand something, or nothing.”

January-February, is glued to the TV watching reports of the Persian Gulf War. He decides to postpone Discovery of America, a book of drawings he is working on: “make a diverting book about America in these days? No!”

As the end of the war approaches, is sorry that victory is tempered by his dark mood. “I don’t work or read any more, only watch TV….More and more I envy friends…who have a Patria in all its particulars: a city, street, house, peasants, children, books, etc. Once the New Yorker Magazine was my homeland. Now all that remains is 75th & Park and my apt.” His letters to Aldo Buzzi become a form of therapy.

April, writes to Buzzi: “Lucky you, who has an authentic language in which you can write instinctively, because it’s the language of your childhood. For me, writing is translating from what I say or read in two acquired languages. Romanian I’ve always ignored…a language of beggars and policemen….At my age, unfortunately, it’s the language that comes back to me when I’m searching for the right word….Certain Romanian words, never used for 70 years or more, leap forth from some corridor of memory.”

In the same self-reflective turn, begins to keep a diary of daily activities amplified by memories, what he calls “an archaeological exercise.” “It’s important for me to find the transition from the dark to the less dark.”

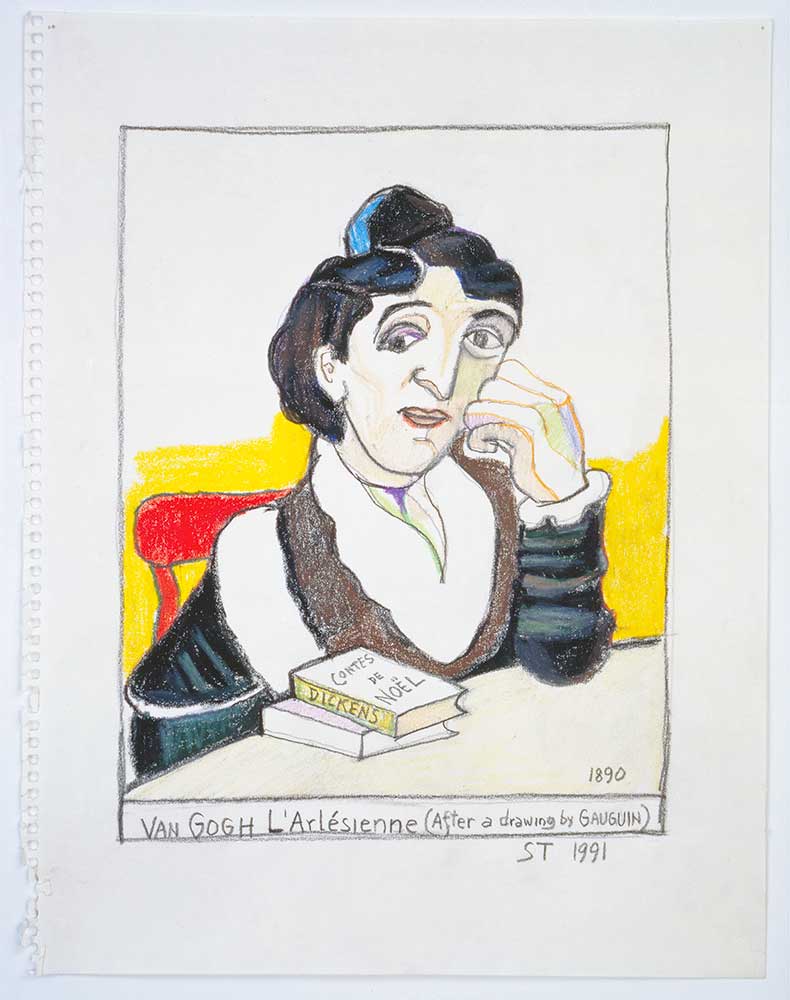

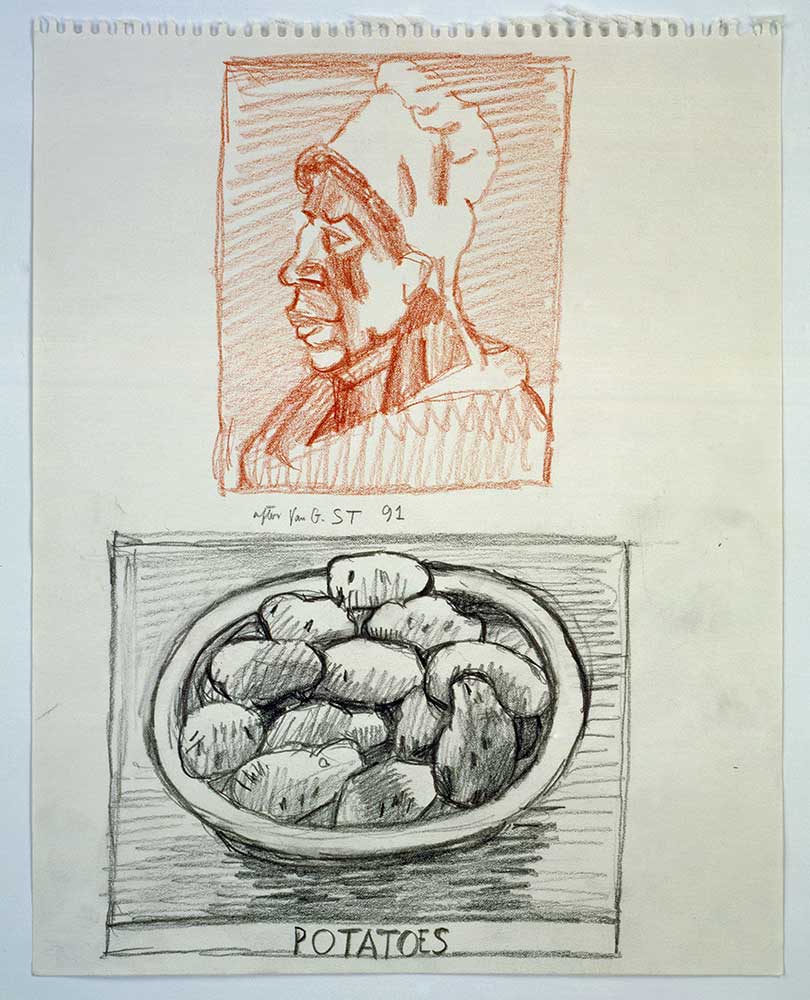

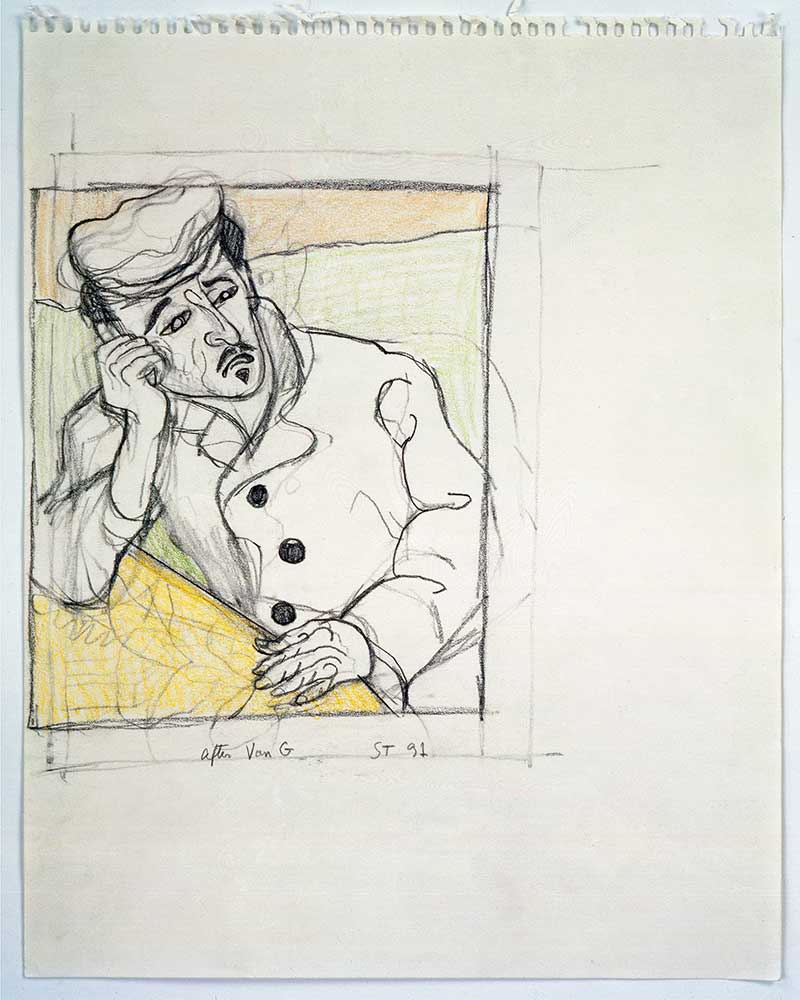

July, to Buzzi: “In these days of emptiness I’m copying from Van Gogh’s paintings, and more and more I observe the influence of the Japanese. Mostly the influence of popular prints, the non-famous ones, which are perhaps more interesting.”

September, decides to submit a drawing from his files as a New Yorker cover, “to be inconsistent, as a joke, to celebrate 50 years with the magazine.” The cover is published on January 13, 1992.

November, having been elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1968, he is now elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, which had merged with the Institute. He reports to Buzzi that the Academy “is the crème de la crème, numbering only 45. I took over Isaac Bashevis Singer’s seat, since he died last year. This election gave me a surprising, unsuspected, and innocent enough pleasure: the pleasure of still being viewed with affection by the majority that voted for me.”

1992

March, sends longtime friend John Updike a drawing for his 60th birthday inscribed “John UP 60!”

June, Sigrid Spaeth attempts suicide with a drug overdose in the Amagansett house; ST finds her and calls for an ambulance.

July, Tina Brown becomes editor of The New Yorker and convinces ST to contribute inside color features and covers.

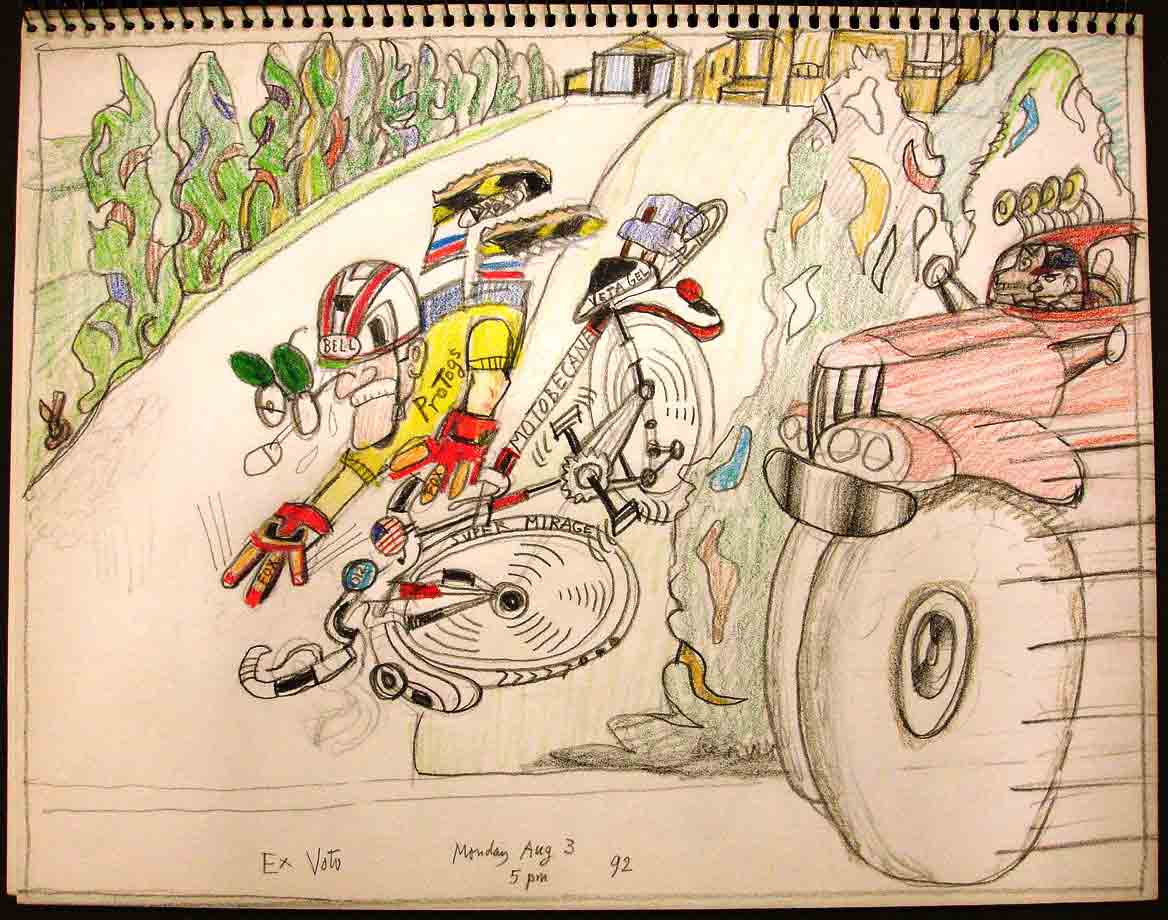

August, tells Aldo Buzzi that he fell off his bicycle but was not seriously hurt. “In my mind I see the disasters I avoided—teeth, bones, eyes—and I understand the concept of the Ex-Voto.” He makes an apotropaic drawing of the event, which recalls a moment he had described to Buzzi in 1983.

Fall, publication of The Discovery of America, with introduction by Arthur C. Danto. The book presents a lifetime of his drawings of American people, places, and architecture. The reviews are good, but he calls it a “celebrity book,” with reviewers treating him like “a celebrity at sunset.”

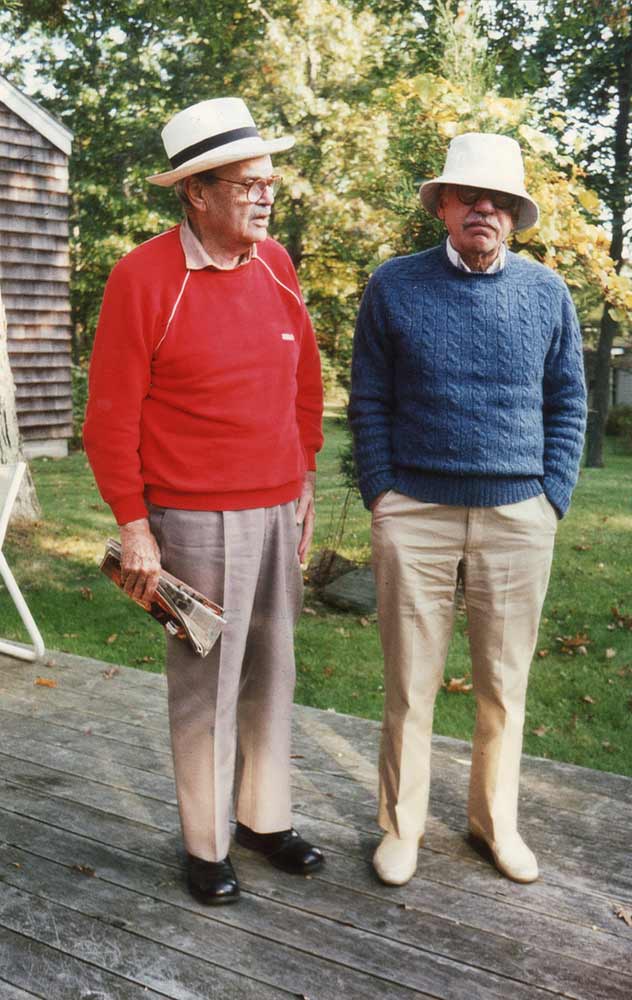

October, Buzzi visits him in Amagansett.

December 5, opening of “Saul Steinberg: The Discovery of America,” at The Pace Gallery, Greene Street, an exhibition celebrating the publication.

December 8, death of William Shawn, former editor of The New Yorker and ST’s good friend. ST had sent him a copy of Discovery of America. Shawn’s admiring response, penned three days before he died, reassures ST that Shawn bore no hard feelings about his decision to resume New Yorker contributions.

1993

Late April, goes to the Buchinger Clinic in Marbella, Spain, on the Costa del Sol, for a regimen of therapeutic fasting. Spends a few days in Paris before returning to New York.

May 8, opening of “Saul Steinberg” at the Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton.

July 31, tells Buzzi: “I stopped reading the NY Times, whose obituaries I kept studying with curiosity—surprising myself—searching, strangely enough, for my own.”

October, Tina Brown urges ST to contribute covers for The New Yorker: “I do miss you from our covers. And I would love to get together with you to talk about doing something special, if you are interested and have not forsaken us.”

November, Françoise Mouly, appointed art editor of The New Yorker in March, contacts ST at Brown’s request. She soon begins working with him to excavate old but unpublished drawings as well as develop new work. The collaboration continues until ST’s death.

1994

January, in a typical process of mental association, he tells Buzzi that for years he’s been wanting to invite his friends Saul Bellow and Leo Steinberg to dinner, “so as to reconstruct the two parts of my name.”

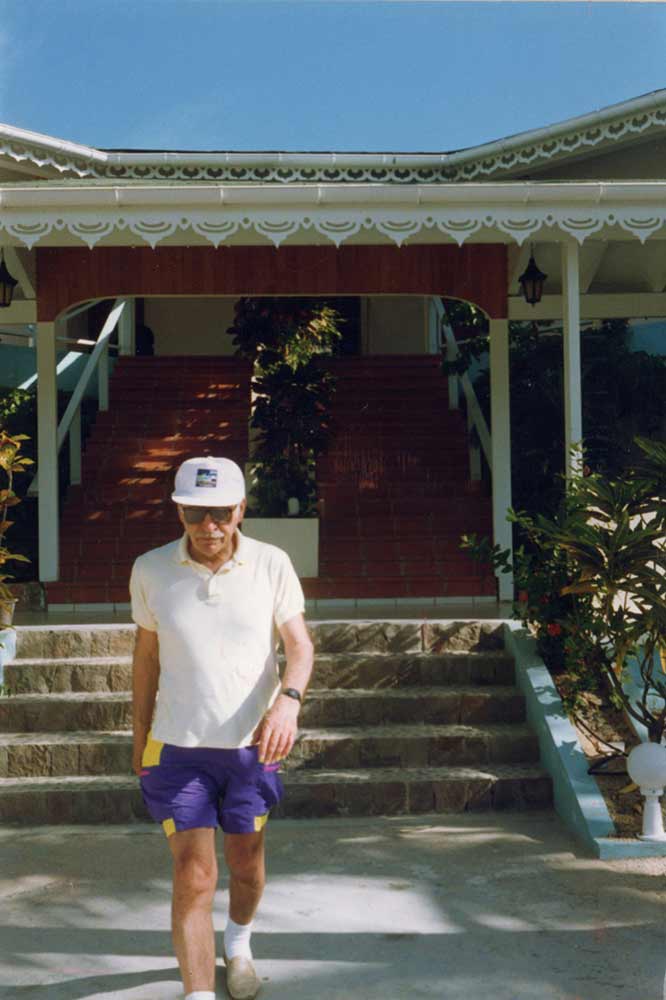

February 15-23, in St. Bart’s, French West Indies, with Sigrid.

March 1-April 20, “Saul Steinberg: Major Works,” Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York. The gallery will now frequently mount Steinberg shows.

April 29-June 11, “Saul Steinberg on Art” at Pace Drawing, New York.

June 28, the day of his birth in the Gregorian calendar, he writes in his diary, “Today I’m 80! With delayed reflexes I now seem kinder, having missed the occasion for an instant nasty retort.”

November 30-December 8, in Guadeloupe.

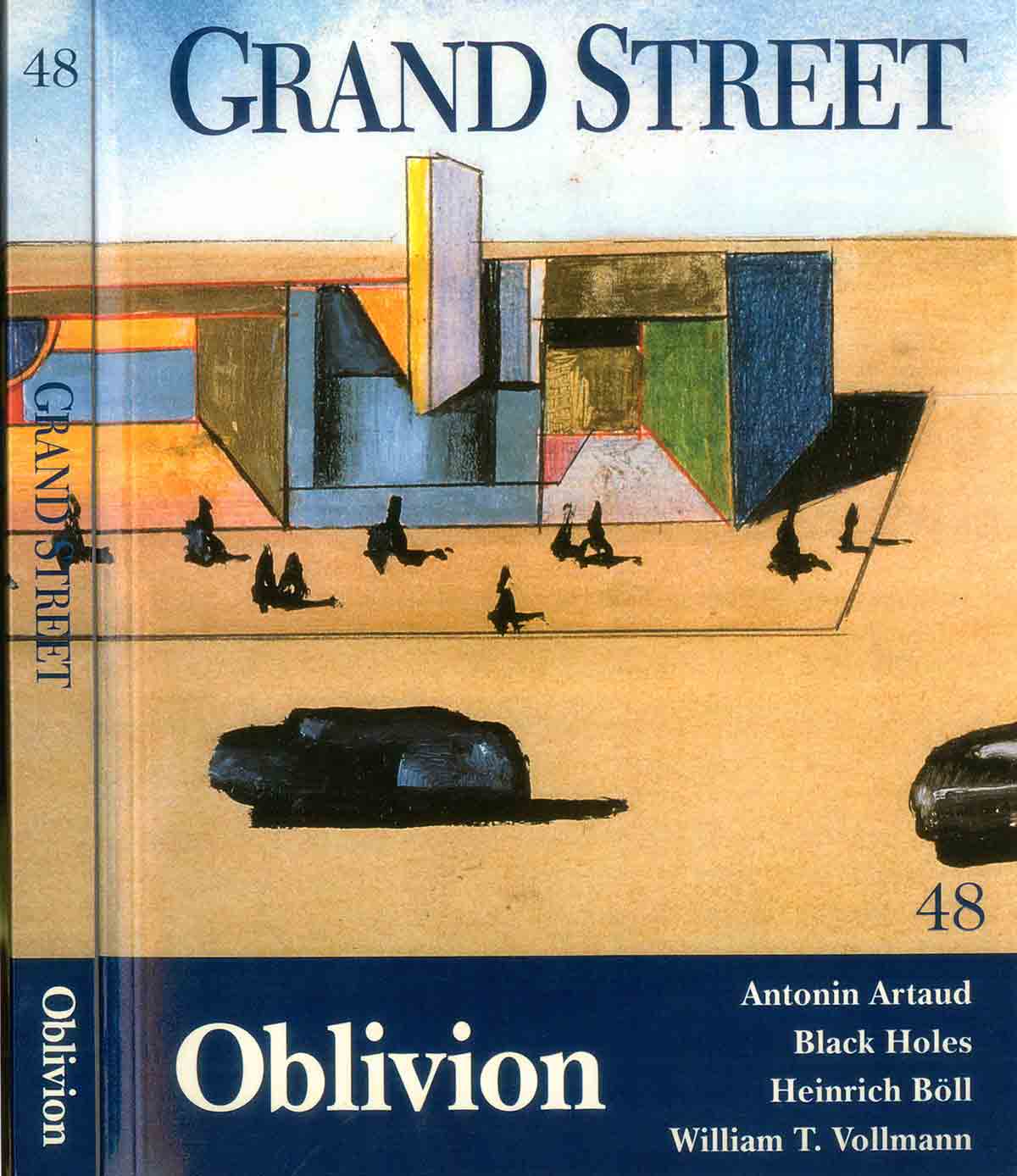

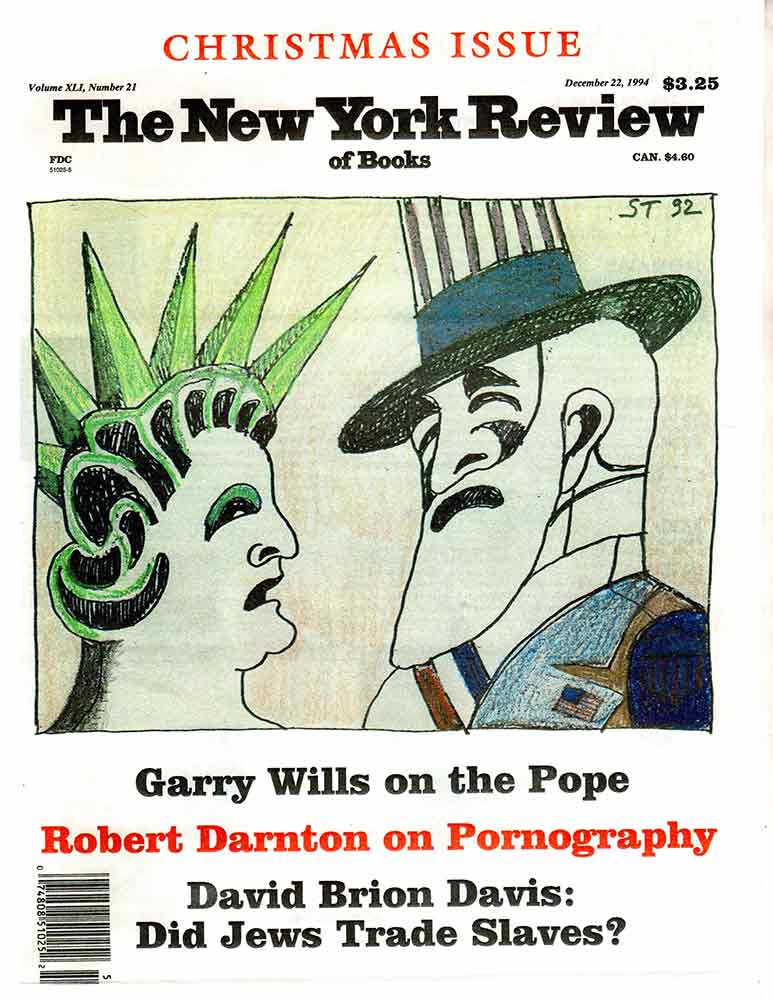

Begins contributing covers and inside art for The New York Review of Books; will continue to do so for the next two years. Resumes contributions to Grand Street: the Winter 1994 issue has an ST cover and portfolio of 13 drawings from the 1970s and 1980s; the Spring 1995 issue has two sketches of Las Vegas.

1995

Is taking an anti-depressant; later in the year will add medication for anxiety.

January, tries to read the typescript of the 1974 and 1977 conversations with Buzzi, which Buzzi still wants to publish, but reports that he can only manage “a few pages.” By April, he has read the whole, calling it the “Book of Saul,” and dislikes the whimsical tone with which he described his early years: “the tragic part of my life treated with allegria!” Reflections and Shadows, as the book came to be titled, will be published posthumously.

Beginning of his friendship with author and Romanian-émigré Norman Manea, who had arrived in the US a few years earlier; ST insists they speak in English.

February 7, to St. Bart’s with Sigrid. The next day she suffers a mental collapse and ST flies her back to New York for hospitalization.

February 27, reports to Buzzi that he’s “transfixed by the O.J. Simpson trial” on TV.

May 24, tells Buzzi that “I’m finally destroying a large portion of my drawings, something I’ve postponed to the future for many years—and now even the future is passing. So I’m in a funereal state.”

October 15, arrives at the clinic in Überlingen in hopes of alleviating his depression. Routine blood tests reveal tumorous activity. Back in New York (after a brief visit to Milan), doctors discover the presence of thyroid cancer, deemed indolent, and no treatment is recommended.

October 20, opening of “Saul Steinberg: About America 1948-1995: The Collection of Jeffrey and Sivia Loria,” Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania. Travels to the Yale University Art Gallery in March 1996.

December, decides to leave his papers to the Beinecke Library, Yale University, “where some librarian, now a baby, will dig out the pearls that I can’t find.”

1996

Complains to Buzzi that his handwriting has become shaky and that his “hand trembles when the spoon takes too lengthy a voyage from soup to mouth.”

His frequent letters to Buzzi have become part daily diary, part voyages to the past—to his childhood and youth in Romania, his student years in Milan, and his military service in World War II.

May 24, tells Buzzi that he has received an invitation from the Romanian Academy, which had proposed awarding him a medal and erecting a statue in his honor. “What to do? Nothing.” Written in Romanian, the invitation provokes a deeply emotional response to the language in which he had been “humiliated, beaten, cursed, and worse—for being Jewish, the only satisfaction those savages had.”

September 24, Sigrid Spaeth commits suicide. Ian Frazier and Buzzi arrive in early October to be with ST; he doesn’t leave his New York apartment and discourages all other visitors.

At Spaeth’s request, her ashes are buried next to a twisted wild cherry tree on the Amagansett property. ST asks that his ashes be buried there too.

1997

January 18, death of Ada Ongari, his girlfriend from his student days in Milan. He had kept in touch with her, directly and through Aldo Buzzi, regularly sent her money, and in the last years contributed to the cost of her nursing home in Erba, Italy. During the 1980s and 1990s, his letters to Buzzi are punctuated with concerns for her well-being.

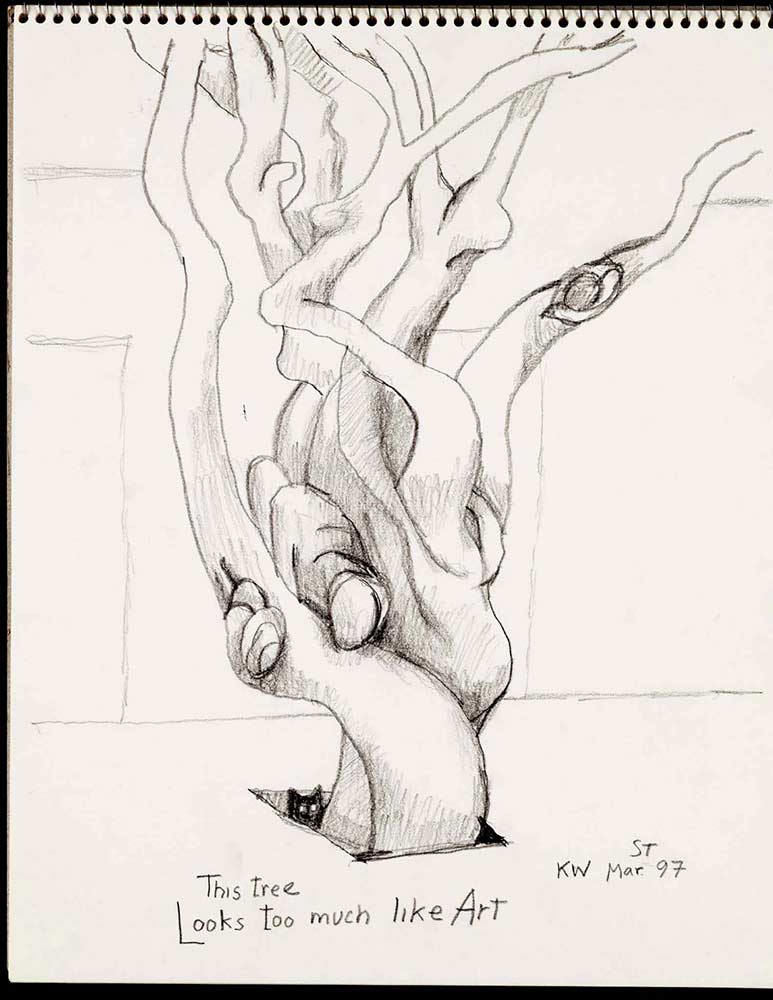

Late February-early April, joins Prudence Crowther, who had rented a small house with a guest cabin in Key West. William Gaddis is also in Key West, and they dine together. On February 22, he writes to Buzzi, “I open my eyes in the morning: great light, and on the ceiling the enormous, silent fan….happy, because I’m staying in this paradise….its strangeness, more than anything else, helps me to forget almost everything. Tiny houses, miniature temples of unpainted wood, dwellings for castaways. Mornings, a 2-km round trip on foot to buy the NY Times with its list of deceased celebrities du jour.”

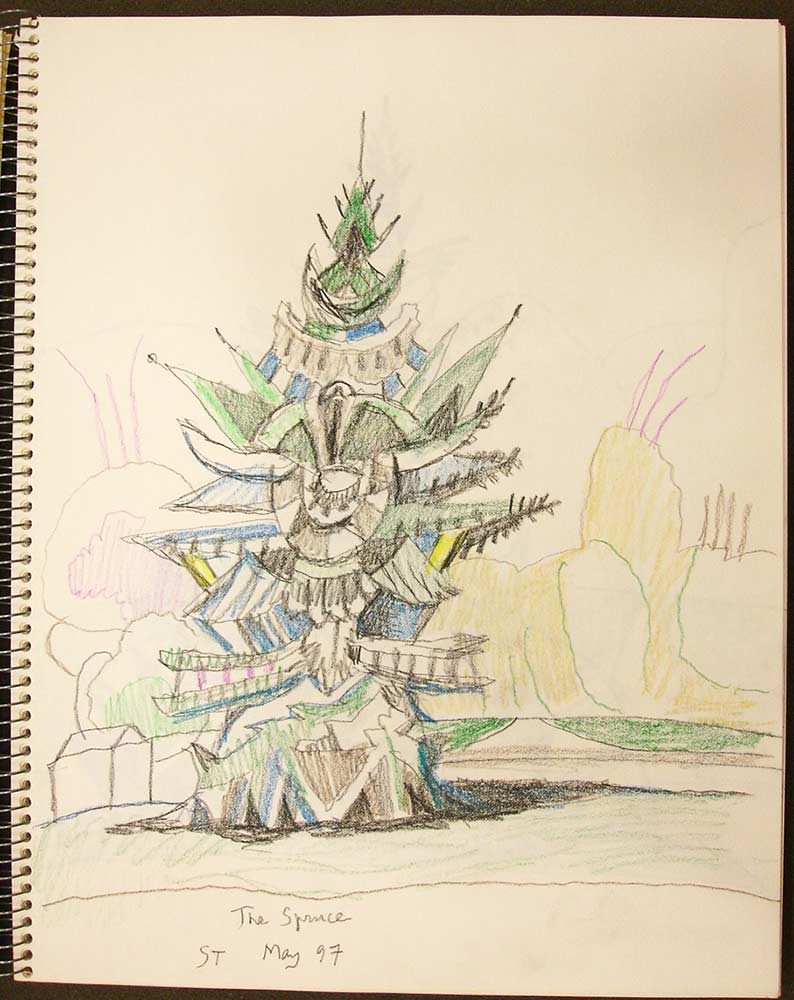

In Key West, makes a series of drawings of a gnarled and moribund tree. Back in Amagansett in May, he turns to a spruce tree on his property.

September 13-November 8, Galerie Bartsch & Chariau, Munich, “Saul Steinberg: Sammlung Sigrid Spaeth.” Spaeth’s collection of ST works, sold by her heirs. In December, the show opens at the Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York.

1998

January-mid-March, in Key West, part of the time with Prudence Crowther; Aldo Buzzi and his companion, Bianca Lattuada, also visit.

Now spends most of his time in Amagansett, returning to New York only for visits to doctors, the dentist, and to attend to business matters.

His depression worsens. “Not good here. Constantly scared by my thoughts (and also by more concrete things),” he writes to Buzzi in April. In May: “I don’t see people because I have to put on a show of normality, man of wit, eloquent. That’s not what I am anymore, an illusion from the past.” And July: “I walk the familiar streets of NY like a ghost.”

August 23, death of his cousin, Henrietta Danson, who had been instrumental in helping him flee Italy and obtain a US visa in 1941-42.

December 16-January 13, after long deliberation, begins a month of shock therapy treatment for depression. During a Christmas break from hospitalization, is devastated to learn that William Gaddis has died—“a blow,” he later tells Buzzi, “from which I won’t recover.”

1999

January 24, to Buzzi: “The annus mirabilis of 1999. The year of my death—I would guess, calmly.”

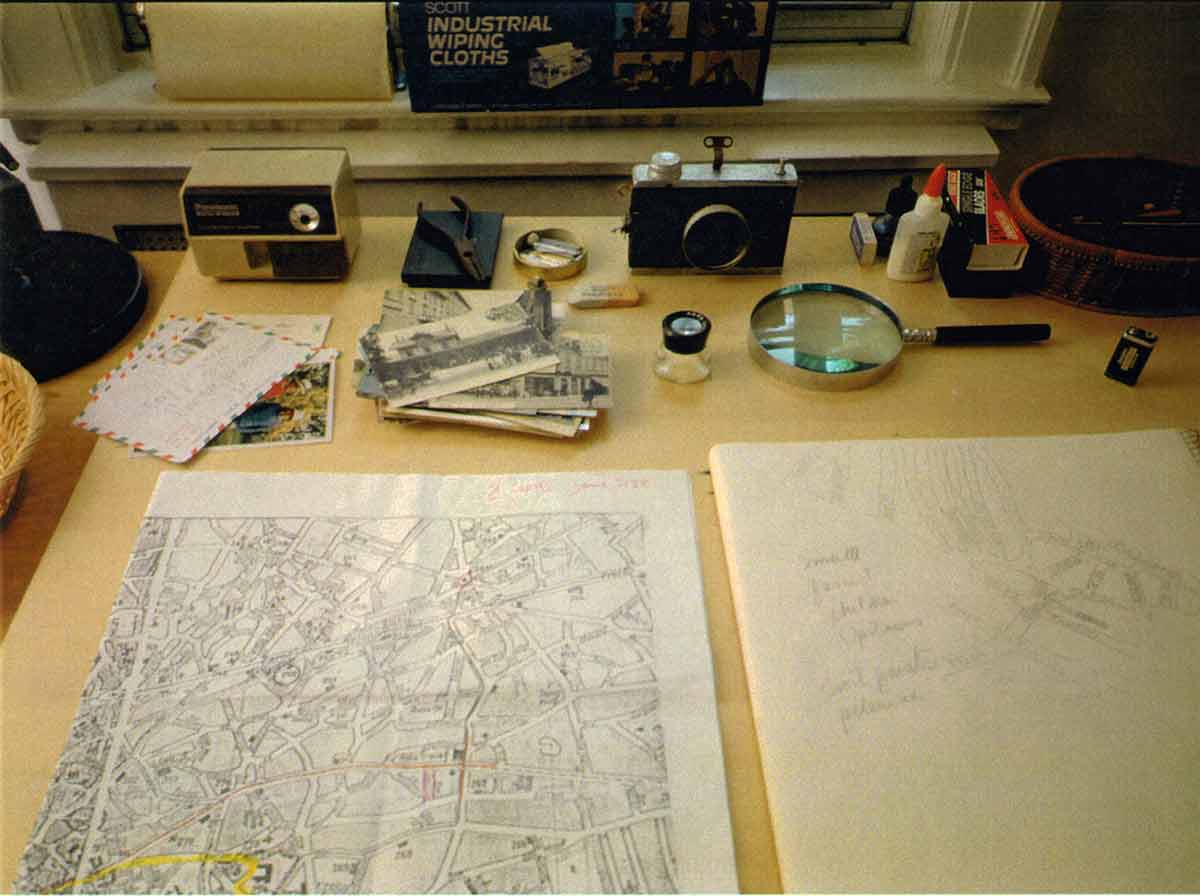

February, on a copy of a 1938 map of Bucharest, he redraws the streets he knew as a boy, “my past in little streets and houses, all of them now demolished.”

February 29–c. March 26, in St. Bart’s with Prudence Crowther.

Early May, diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. As he lies dying in the upstairs bedroom of his New York apartment, Prudence, Aldo Buzzi, Ian Frazier, and Hedda keep vigil, while other friends come and go. He dies on May 12.