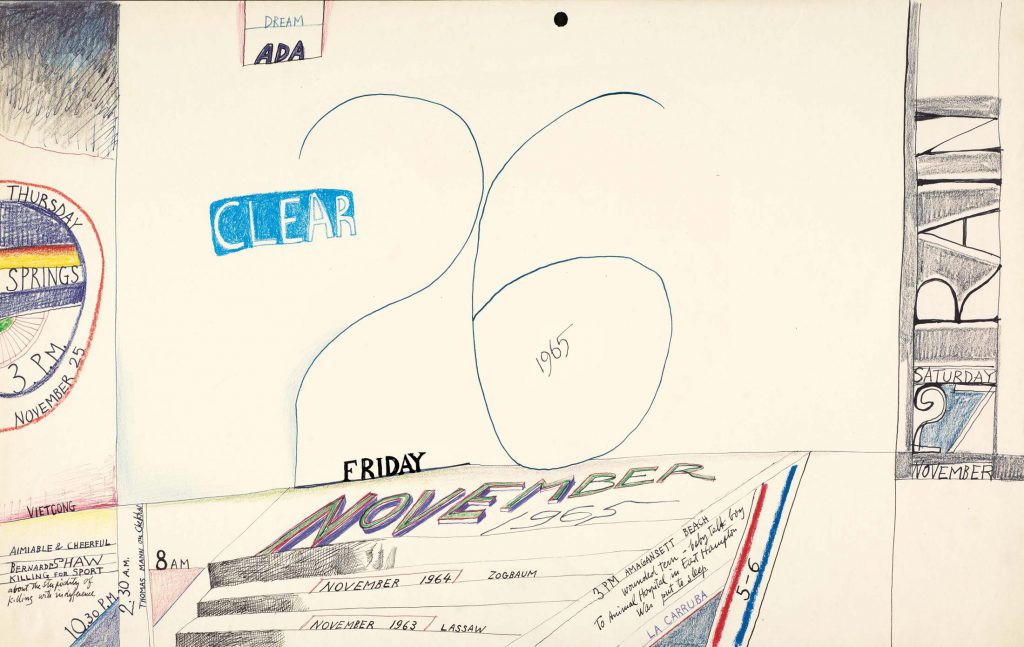

The specifically autobiographic character of the Drawing Tables is not without precedent in Steinberg’s oeuvre, though the clues are usually more indirect: the table in a c. 1954 still life is covered with Steinbergian sketches; the drawing entitled November 26, 1965 portrays a day in the artist’s life, calendar style.64

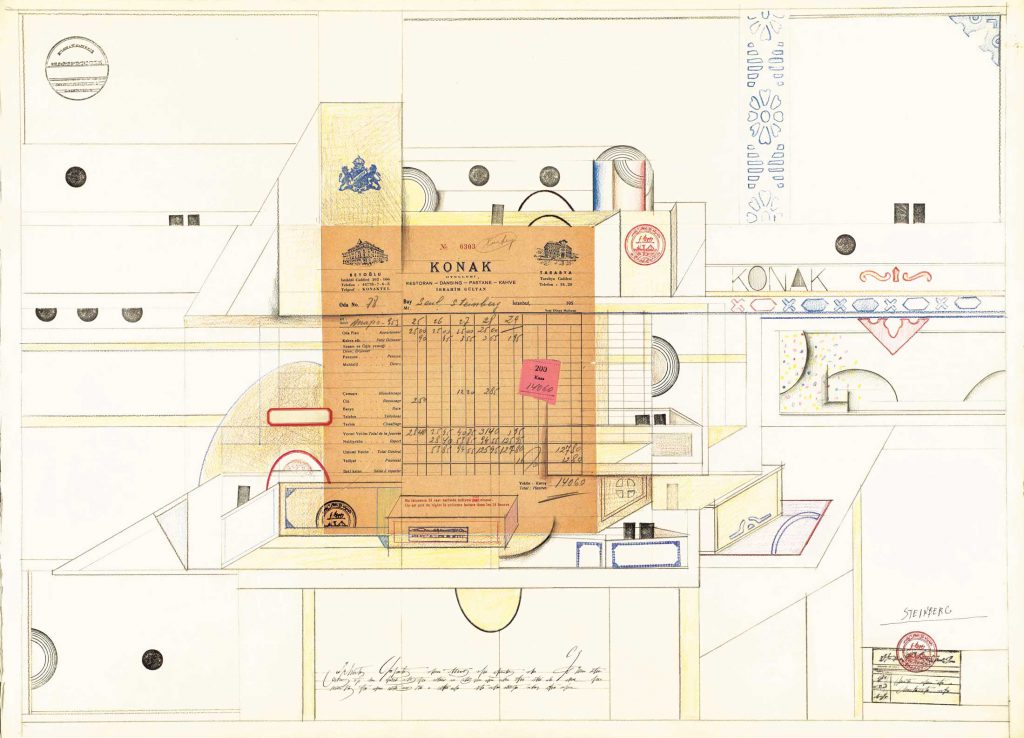

Apr 12 1969 subtly announces the draftsman’s presence by embedding the date of execution within Cubist geometries; dead center in Konak is the collaged hotel bill Steinberg kept from his 1953 stay at the Istanbul hotel.65

But undisguised autobiographical glimpses of Steinberg the artist enter with the Drawing Table reliefs and continue in both sculpture and drawing till the end of his life.

As for the man Steinberg, pictorial autobiography also emerges around 1970.

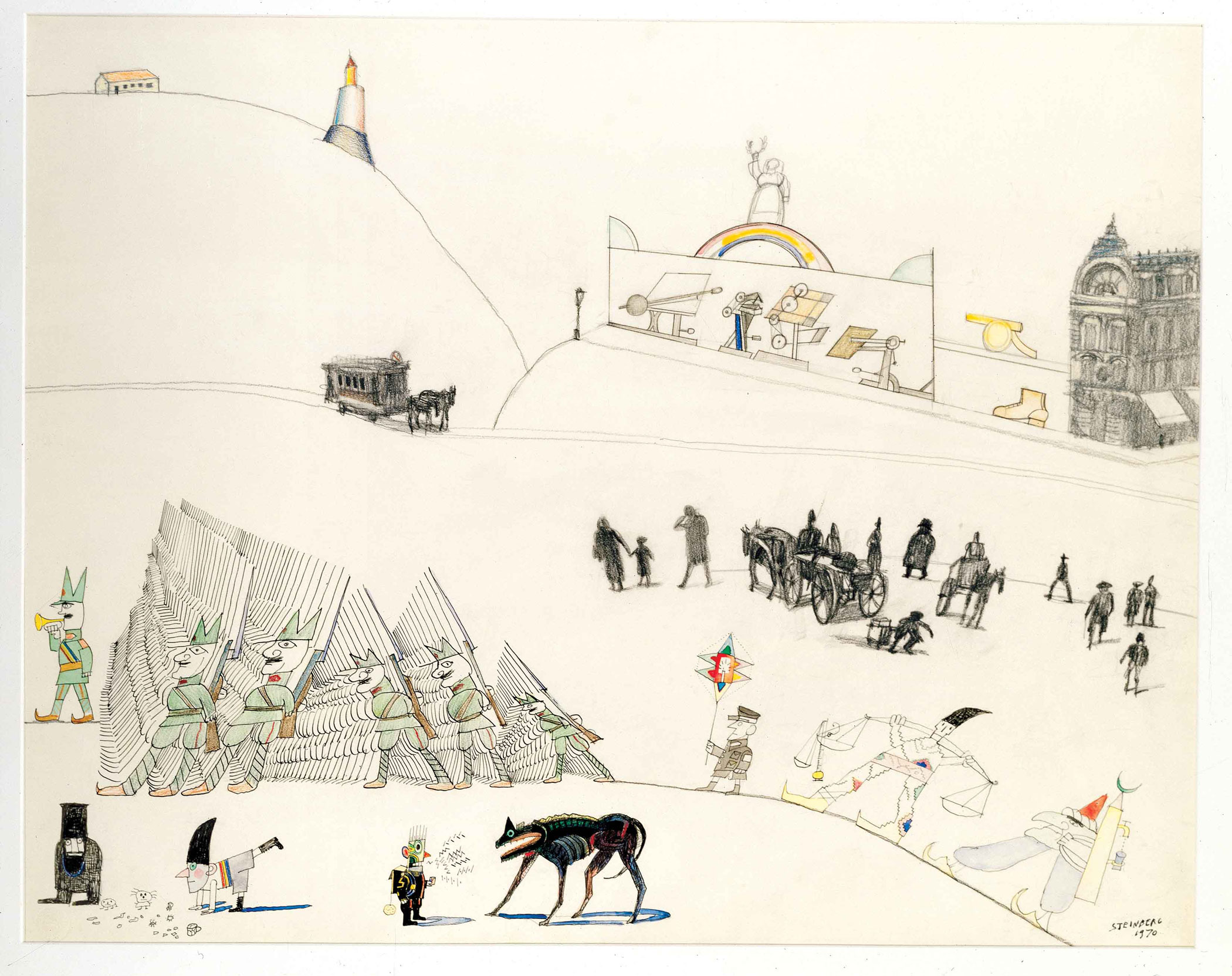

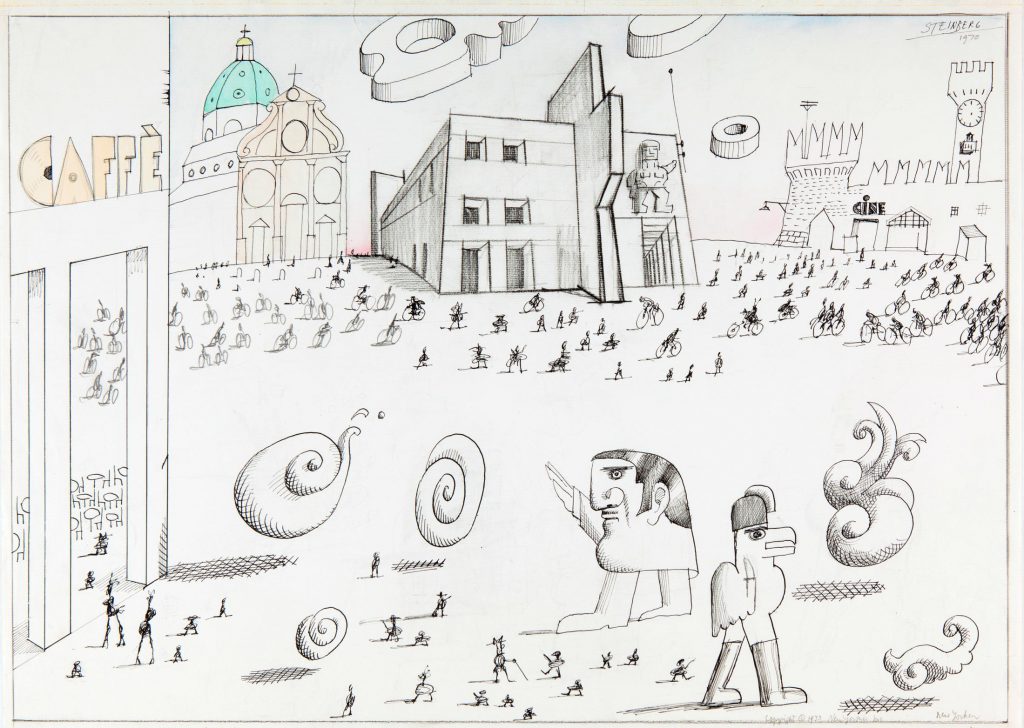

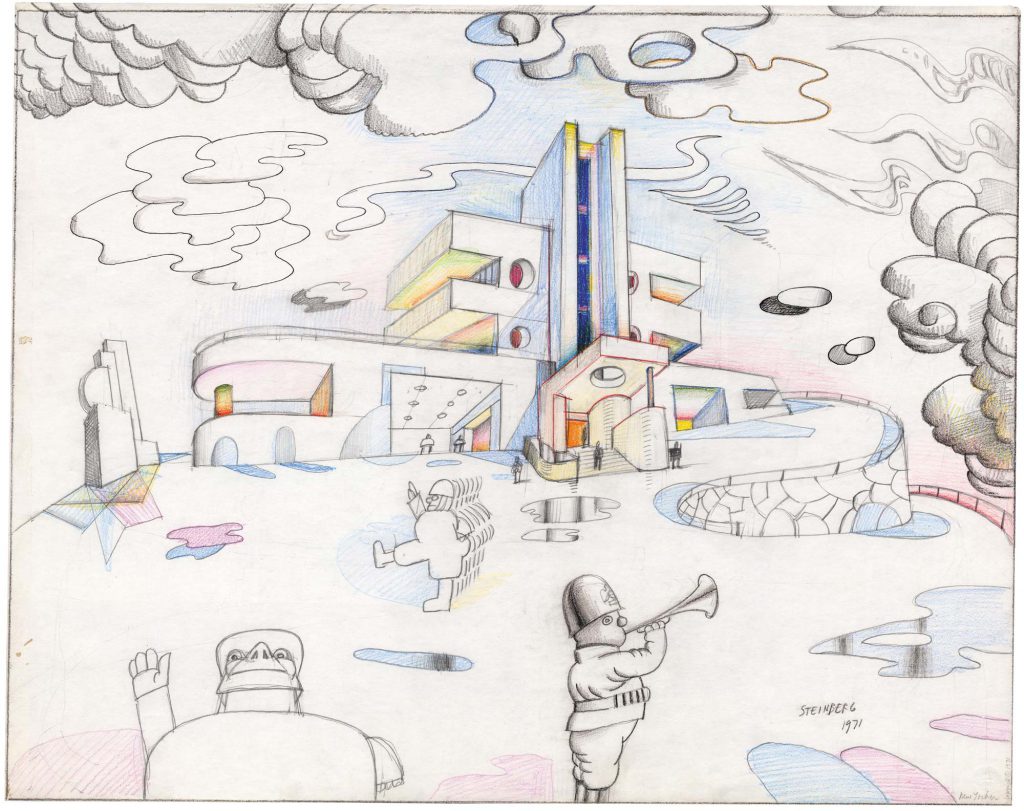

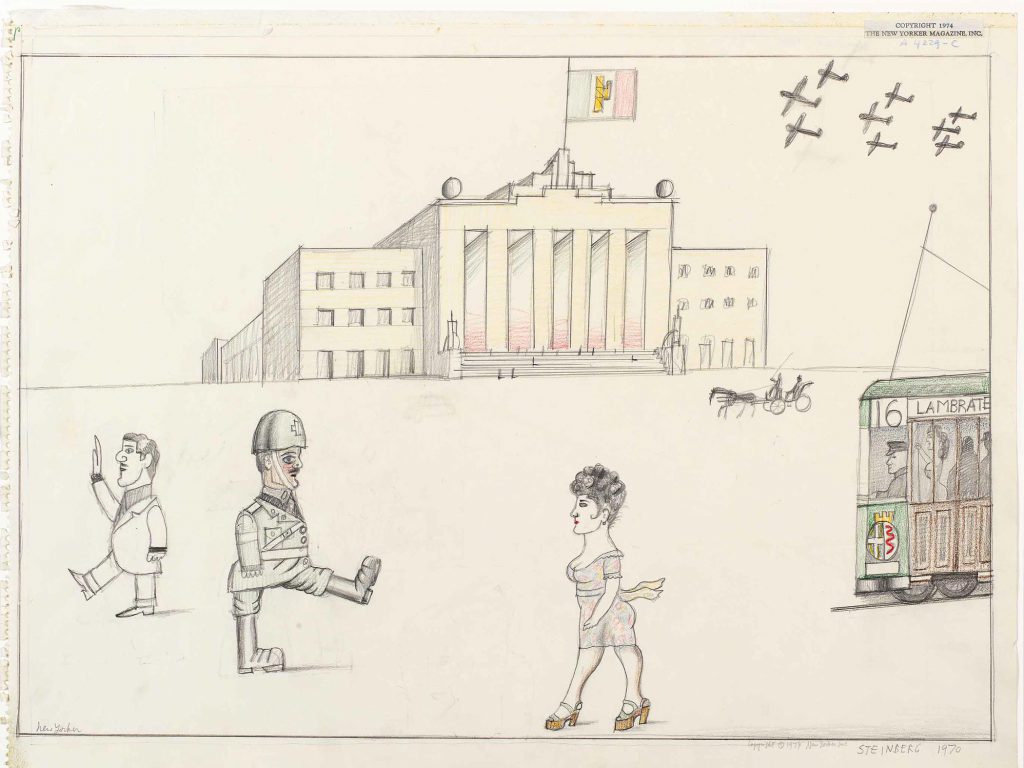

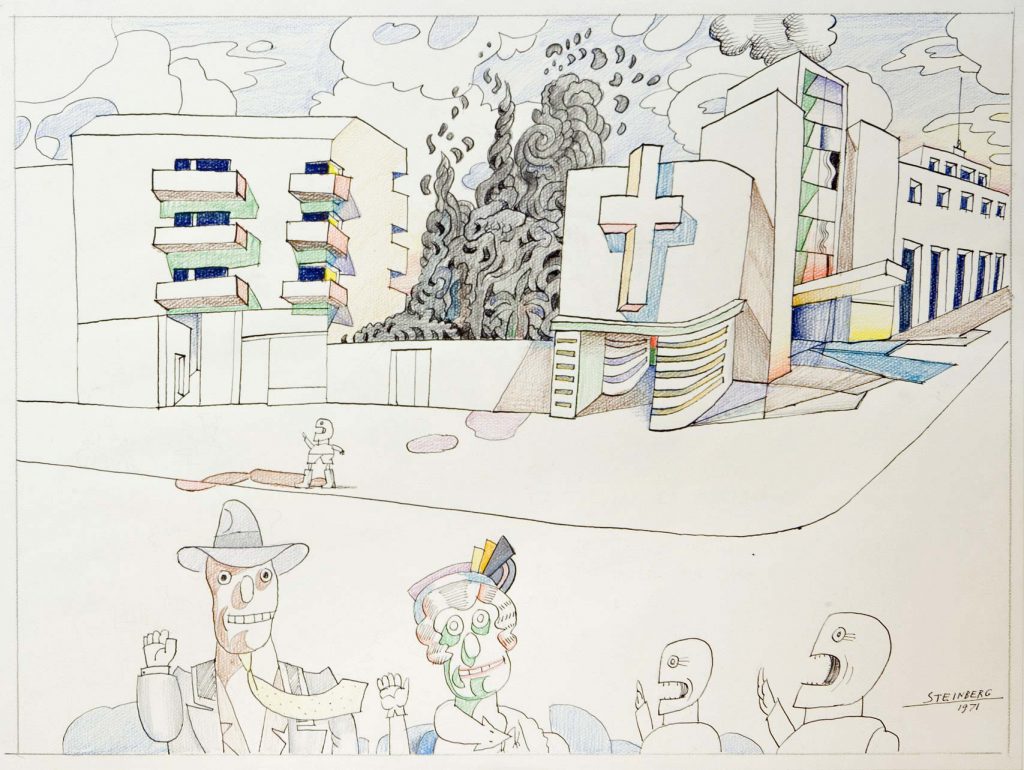

It appears in independent drawings as well as New Yorker portfolios, the latter including a series of 1970-71 that—for the first time— reflects on his Italian years in the 1930s. In these works, some published in a 1974 New Yorker portfolio titled “Italy—1938,” Steinberg turns the Bauhaus and Rationalist architecture he’d learned at the Politecnico into an indictment of Fascist repression, where buildings back streets populated with saluting soldiers and citizens.

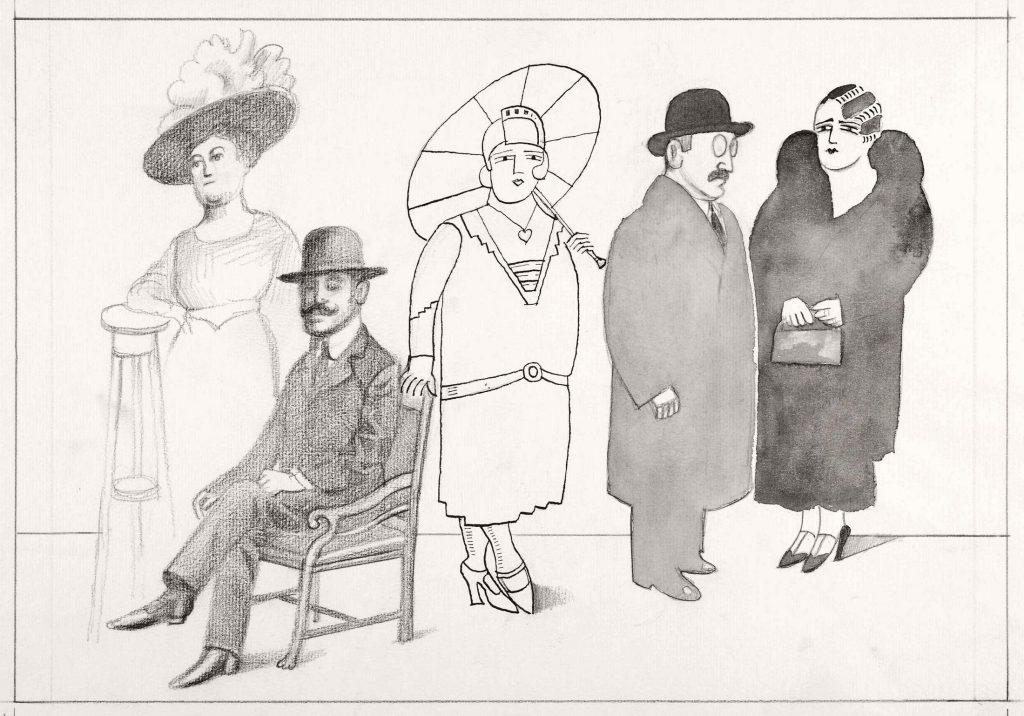

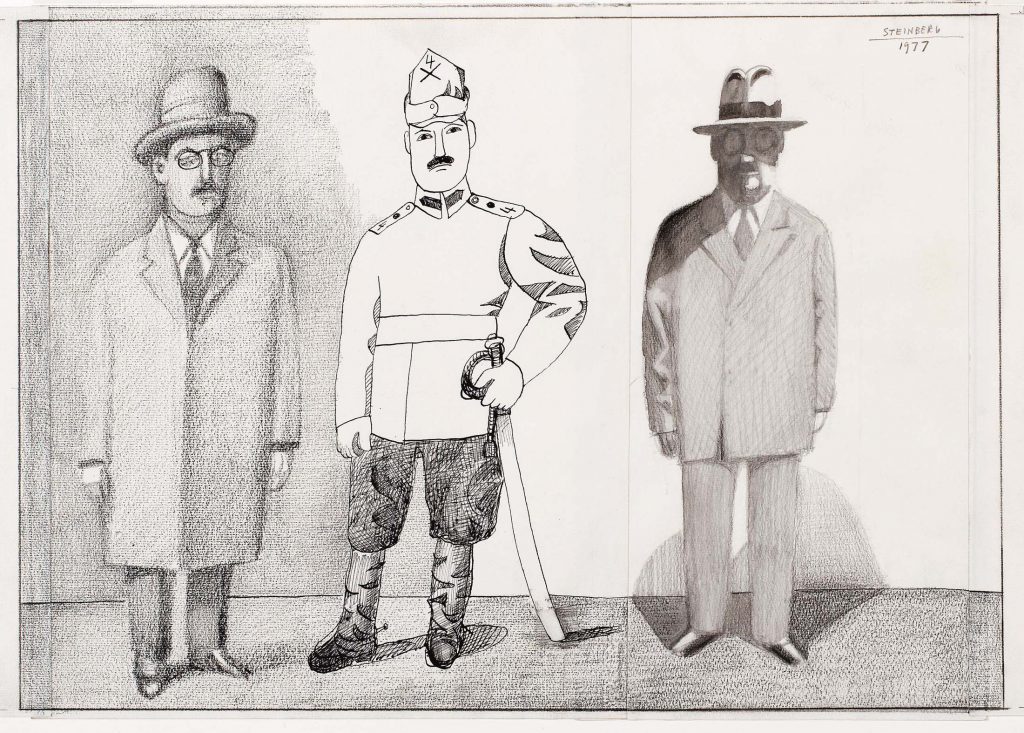

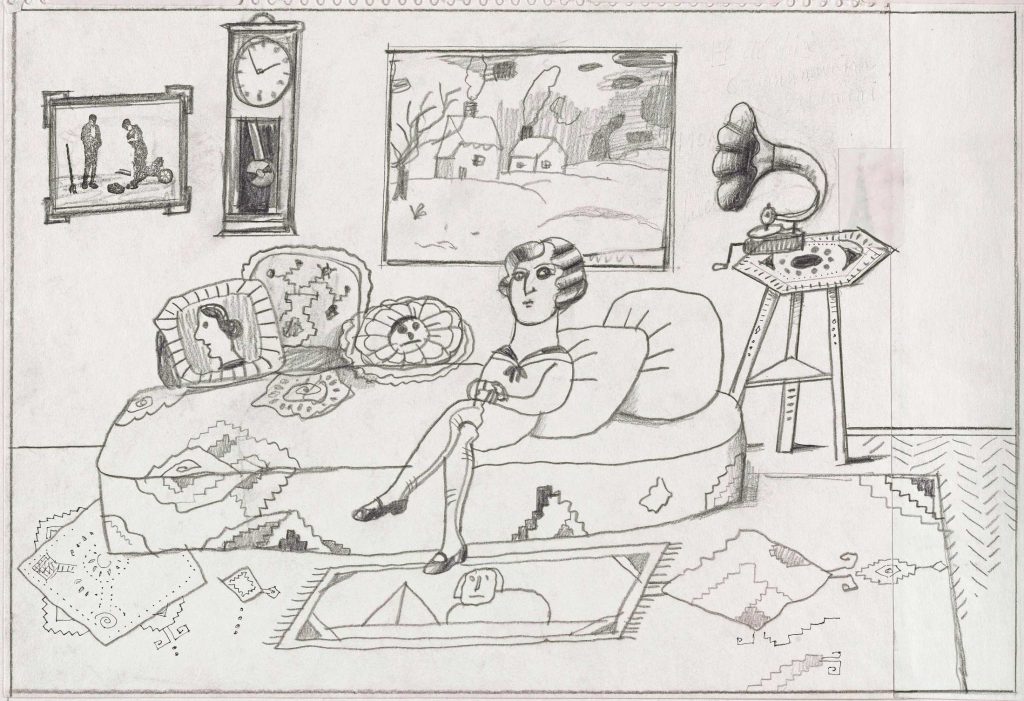

Steinberg’s personal history continued to provide subject matter as the decade progressed, probably in response to a project he undertook with Aldo Buzzi. In the summers of 1974 and 1977, Buzzi taped conversations with his old friend, in which Steinberg addressed his early life in Romania and Italy no less than issues of art.66 Speaking about his past, and reading the transcriptions of the tapes, seems to have spurred him to give pictorial form to his recollections. Two New Yorker portfolios as well as independent drawings envision his boyhood in Romania, first in “Uncles,” where the older generation, dressed in their Sunday best, lines up like proper Central European bourgeoisie.

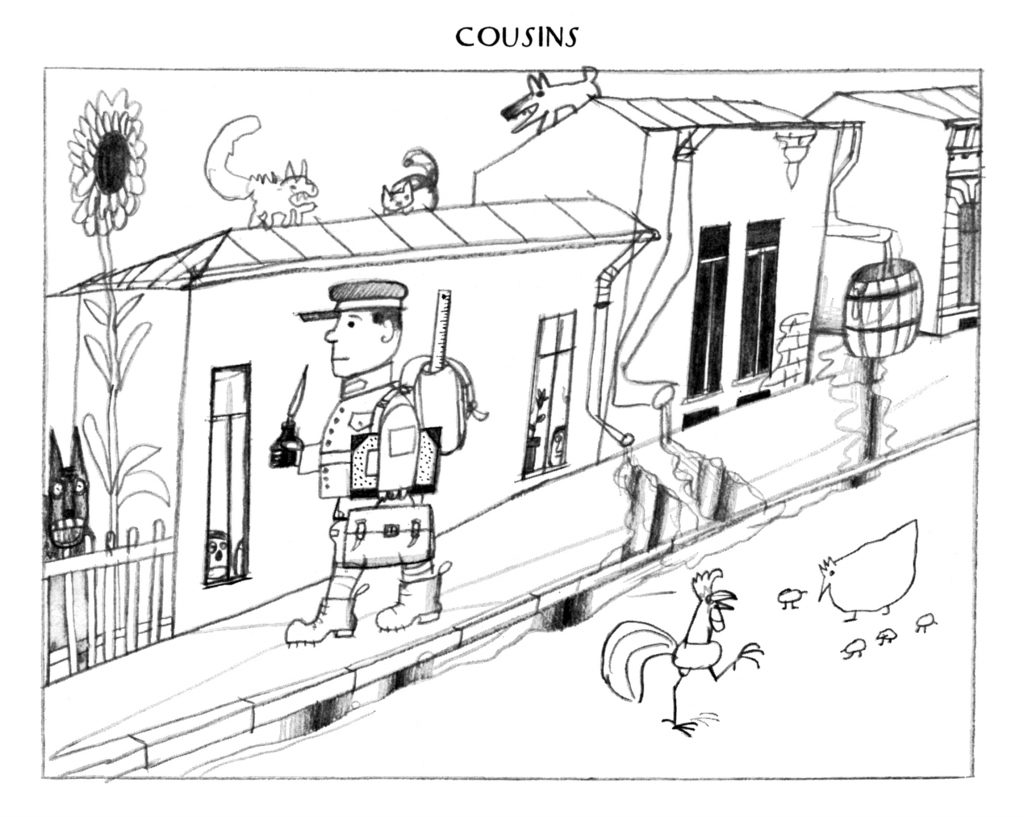

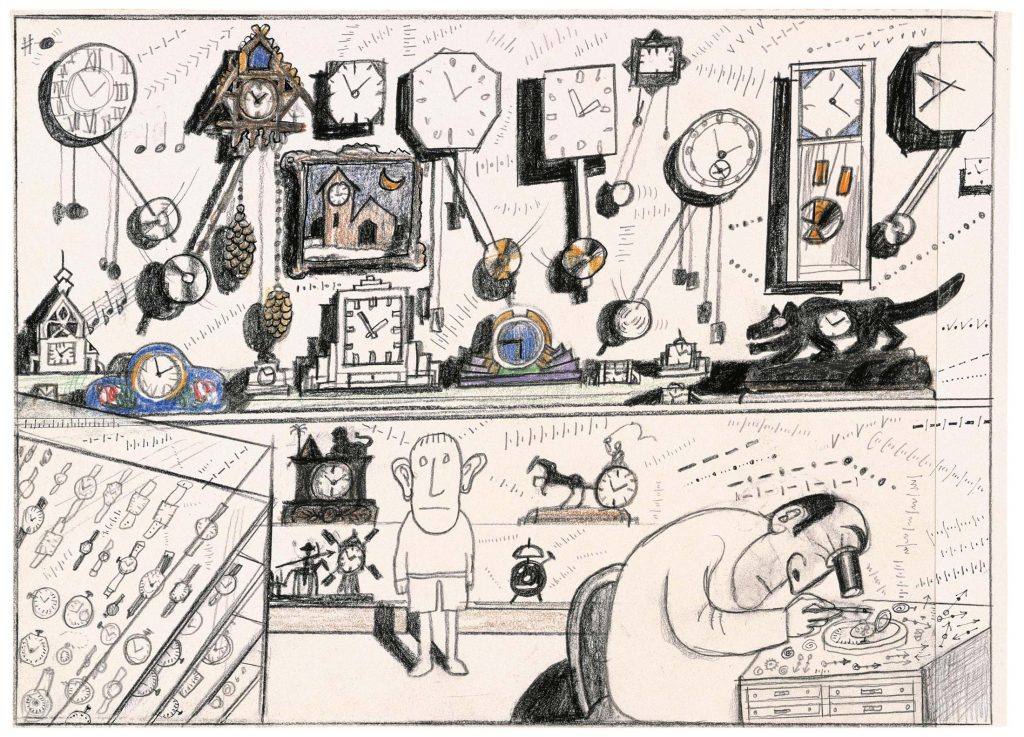

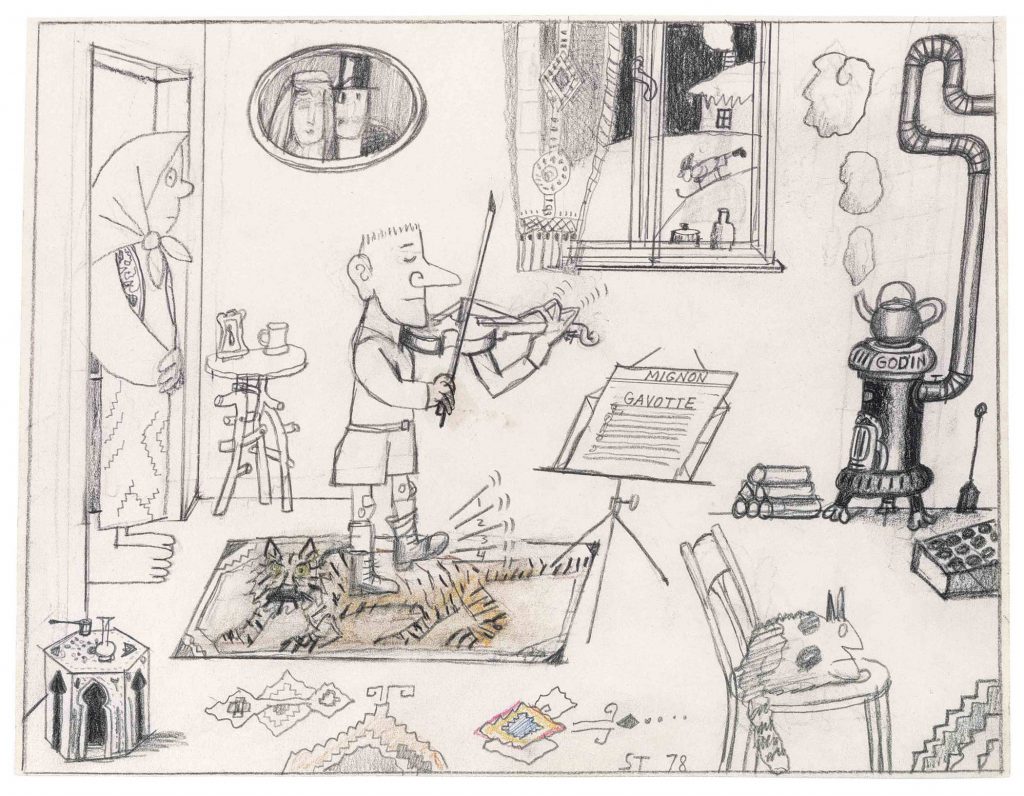

In the six-drawing “Cousins” portfolio, Steinberg appears three times —in school uniform, wide-eyed in his uncle’s watch shop, and practicing the violin.

But whatever reality underlies these images is overpowered by visual humor. He “feared autobiography—the last refuge of the scoundrel,” which may explain why even these works remain emotionally distant, oblique in their personal revelations.67

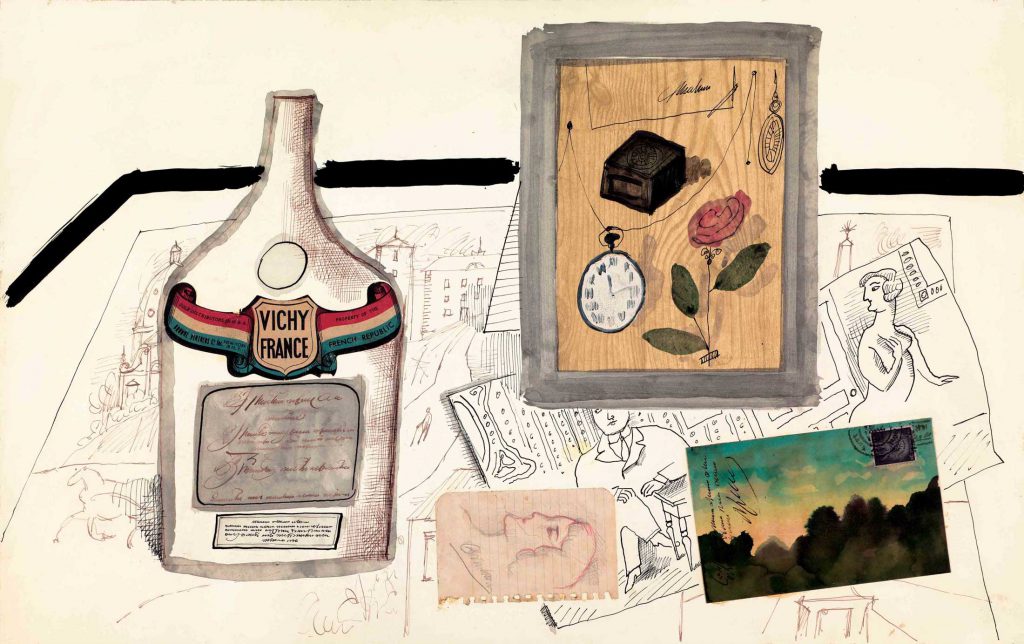

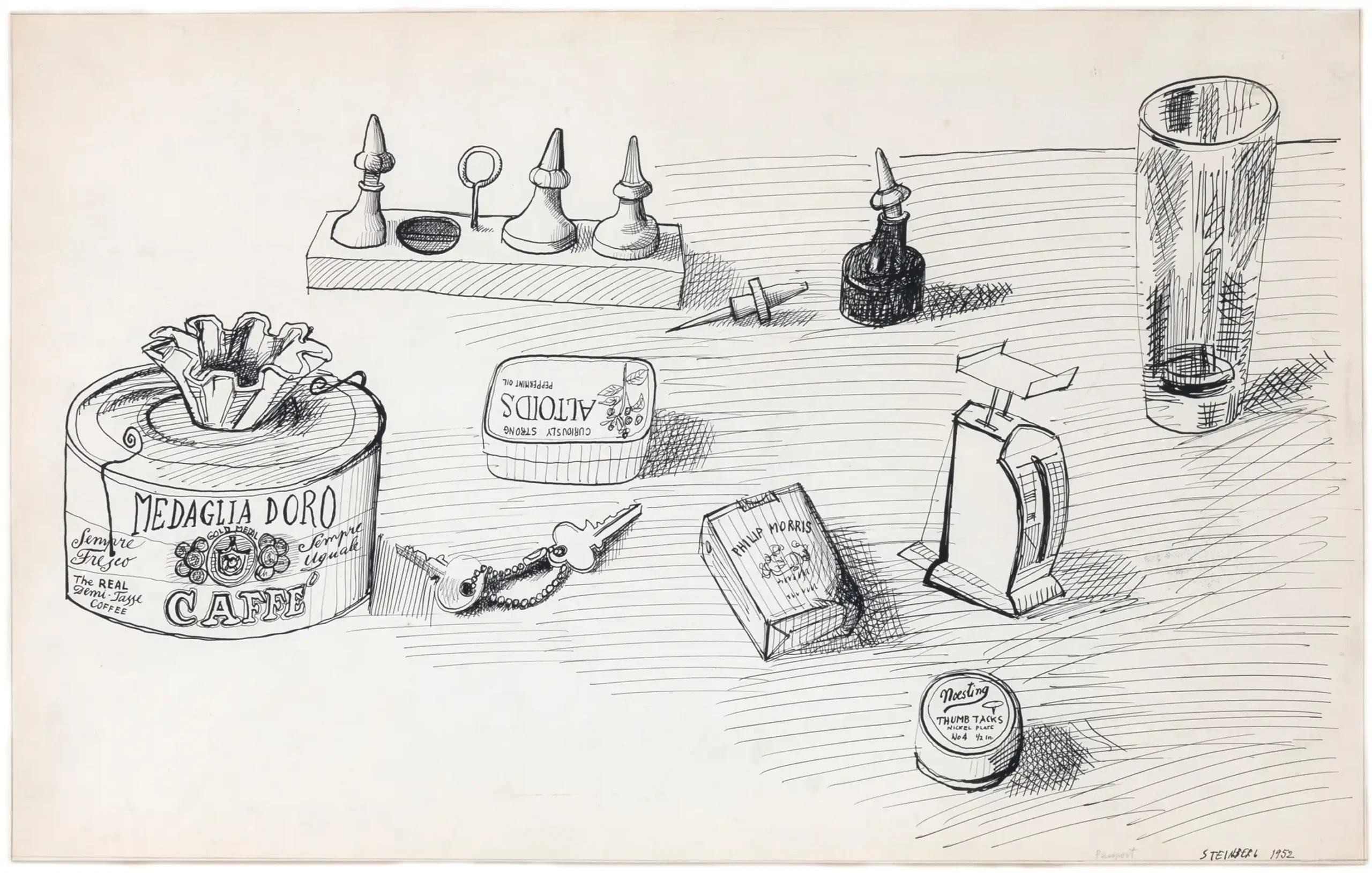

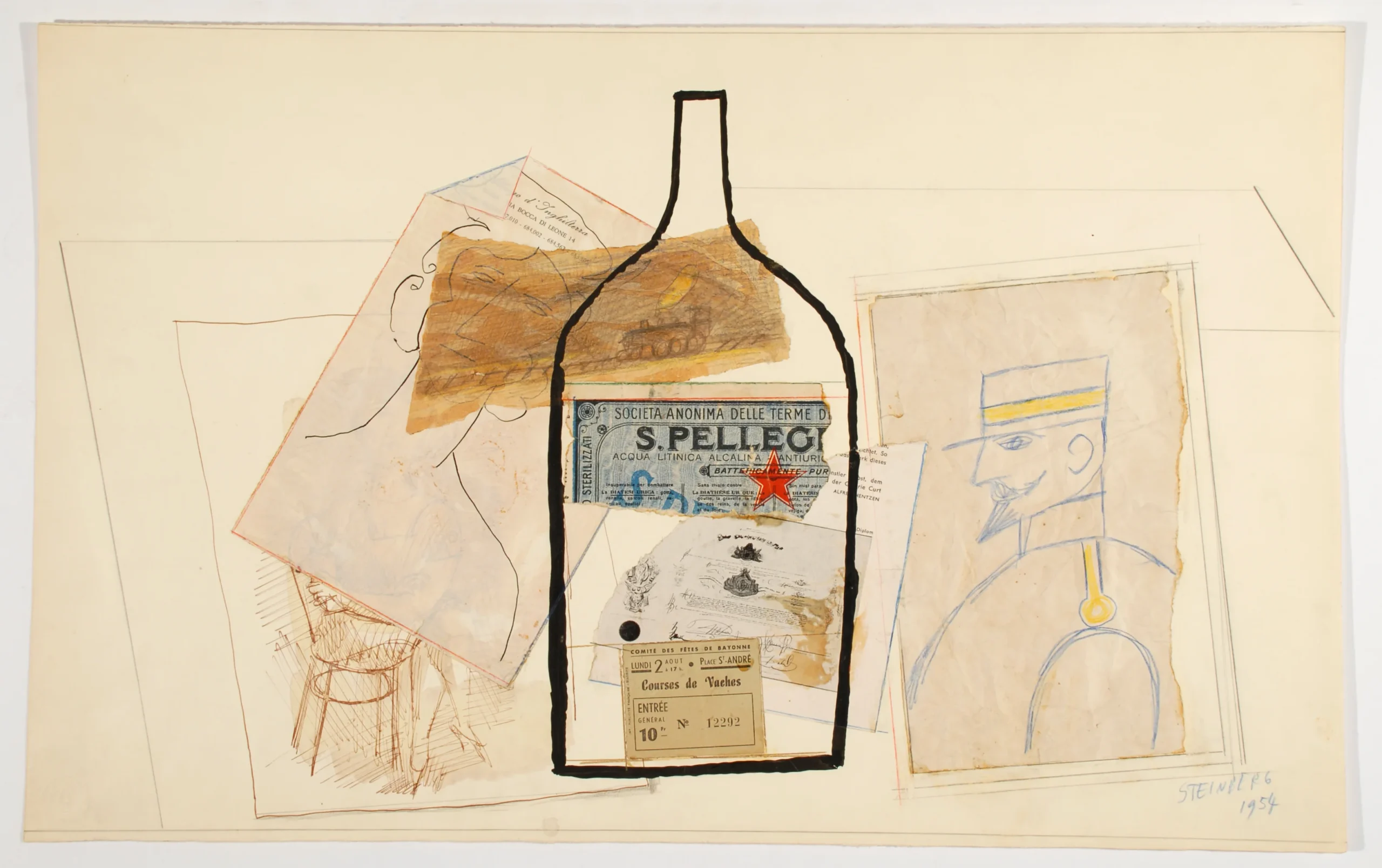

ST’s forays into the still-life genre, which proliferated beginning in the 1970s, likewise represent indirect autobiography, especially in their radical departures from tradition. Whereas conventional still lifes commemorate the bounty of a table or, in the Vanitas type, send a moralizing warning, or, from Impressionism on, explore modernist styles, Steinberg’s still lifes are purely autobiographical, filled with the objects and implements that populated his homes or came off his drawing table. One 1952 still life falls into this class; in others, such as the Vichy Water Still Life at the head of this section or an untitled work of 1954, bottles created by collage anchor an array of ST drawings.

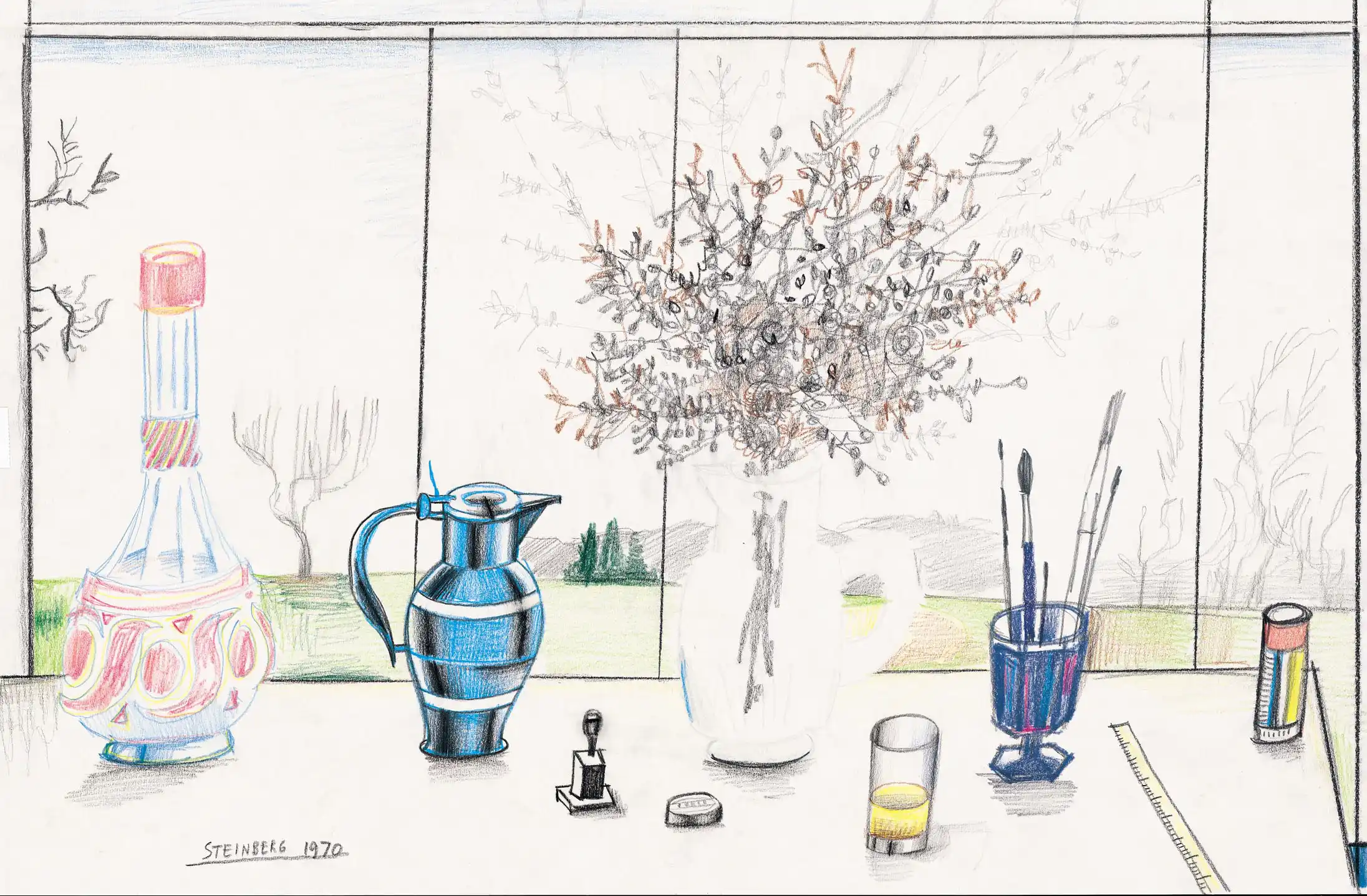

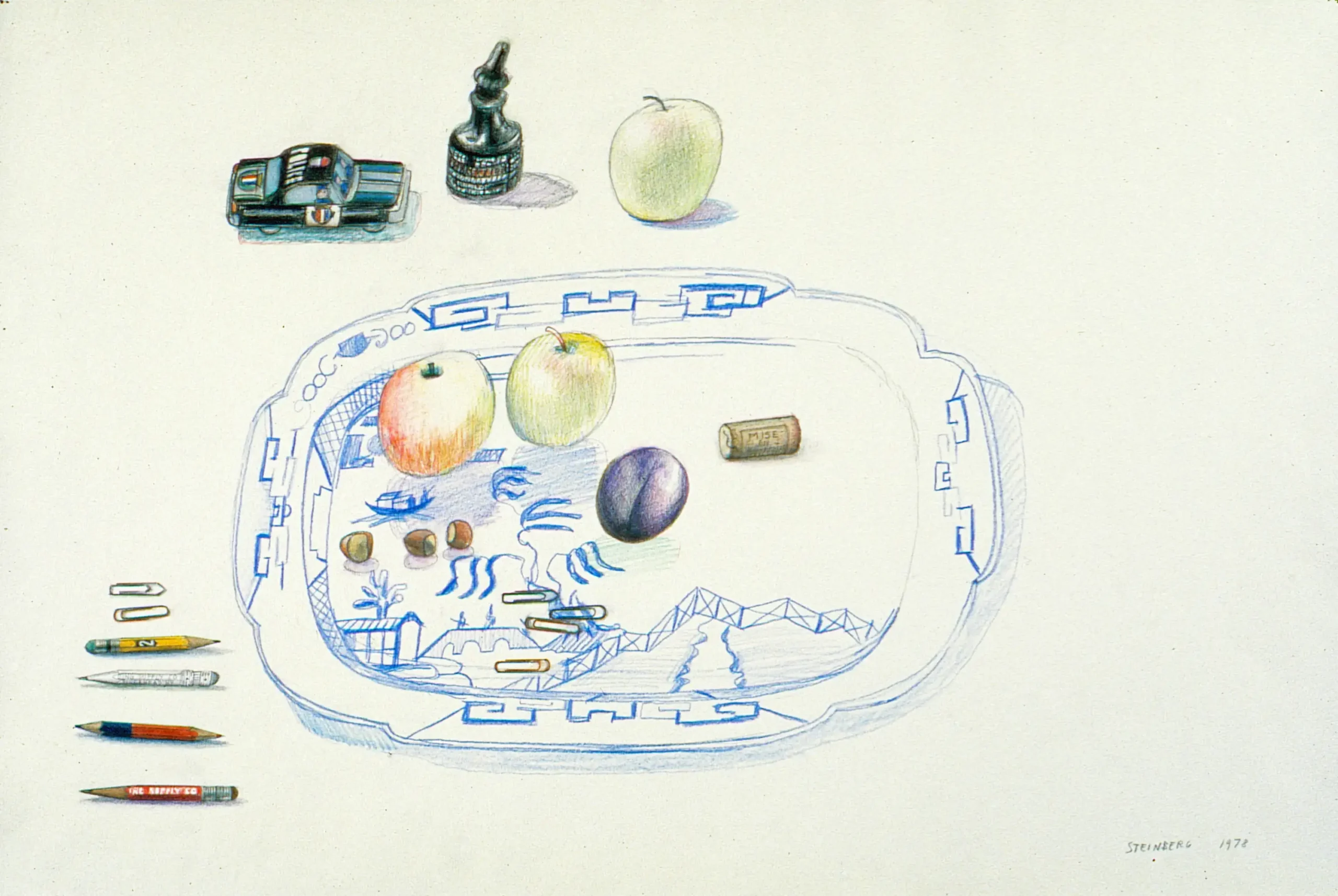

But Steinberg’s intense engagement with still life, contemporaneous with his Drawing Table Reliefs, began around 1970, with naturalistically rendered objects, exquisitely drawn in watercolor, ink, or pencil, and set down on a table. Here too the objects are autobiographical—the population of the tables and shelves of his Amagansett house. Among them are the Willow Pattern platter and jar—frequent visitors to his still lifes—along with empty cans of nuts, sweets, and coffee, often repurposed as pencil and brush holders. (Some of these components can be found in situ in the drawings published in Dal Vero in 1983.) They tend to be loosely spaced or arranged frieze-like, as if to highlight their individual character, unlike tightly composed and visually concentrated classical compositions.