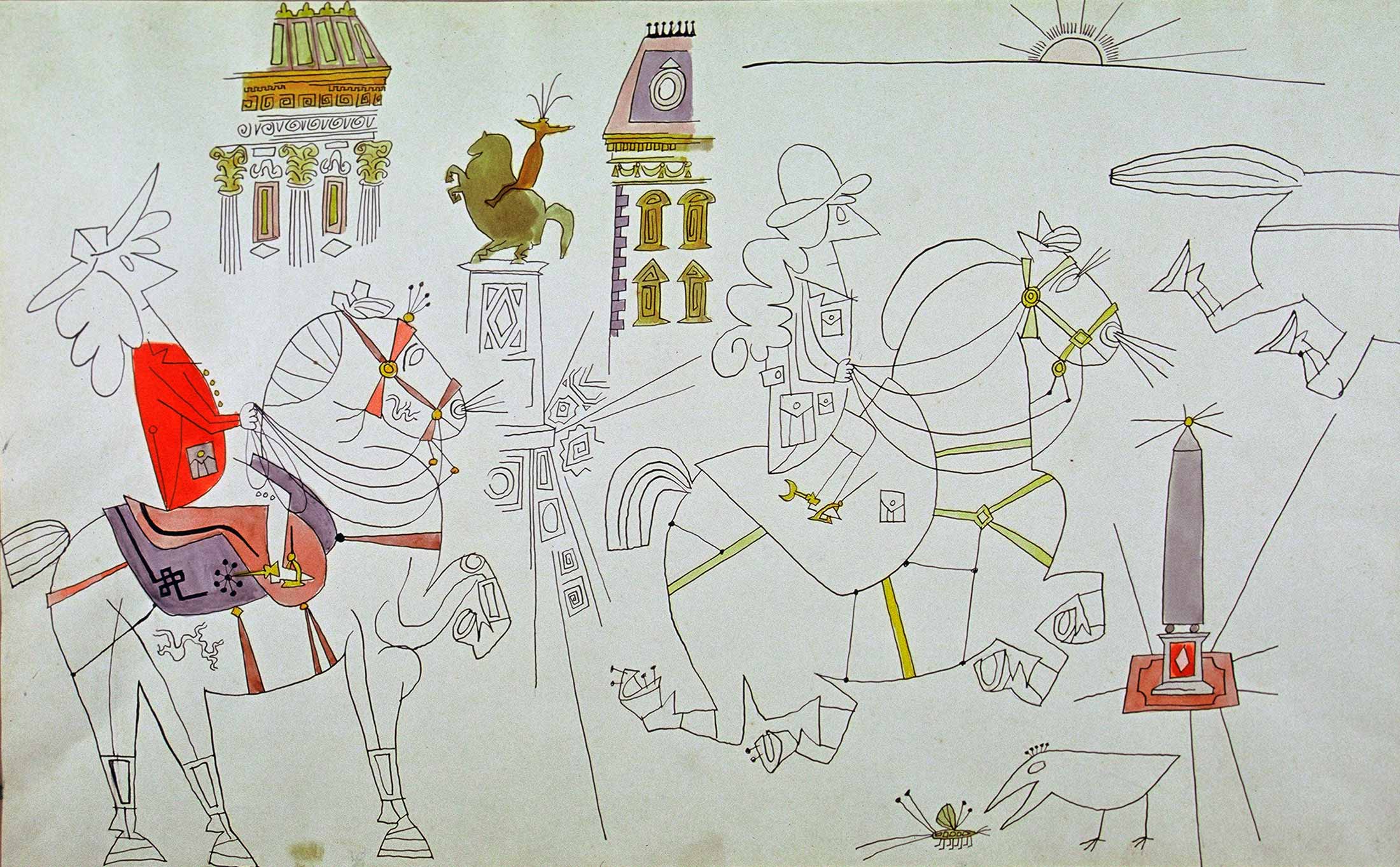

From the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, Steinberg had an active career as a muralist, though the works are little known, some having been destroyed, others disassembled. In these years, he completed eight mural projects in the US and Europe and turned down many more.24 The murals, writes Joel Smith, “demanded a merger of technical ingenuity and visual invention, as [Steinberg] experimented to fit a page-illuminator’s style to architectural scale.” The first mural (1947; now destroyed) was a Central Park equestrian scene for the seventh floor of the Bonwit Teller department store in New York. Steinberg provided drawings, one of which survives, that were then turned into a mural by hired hands.

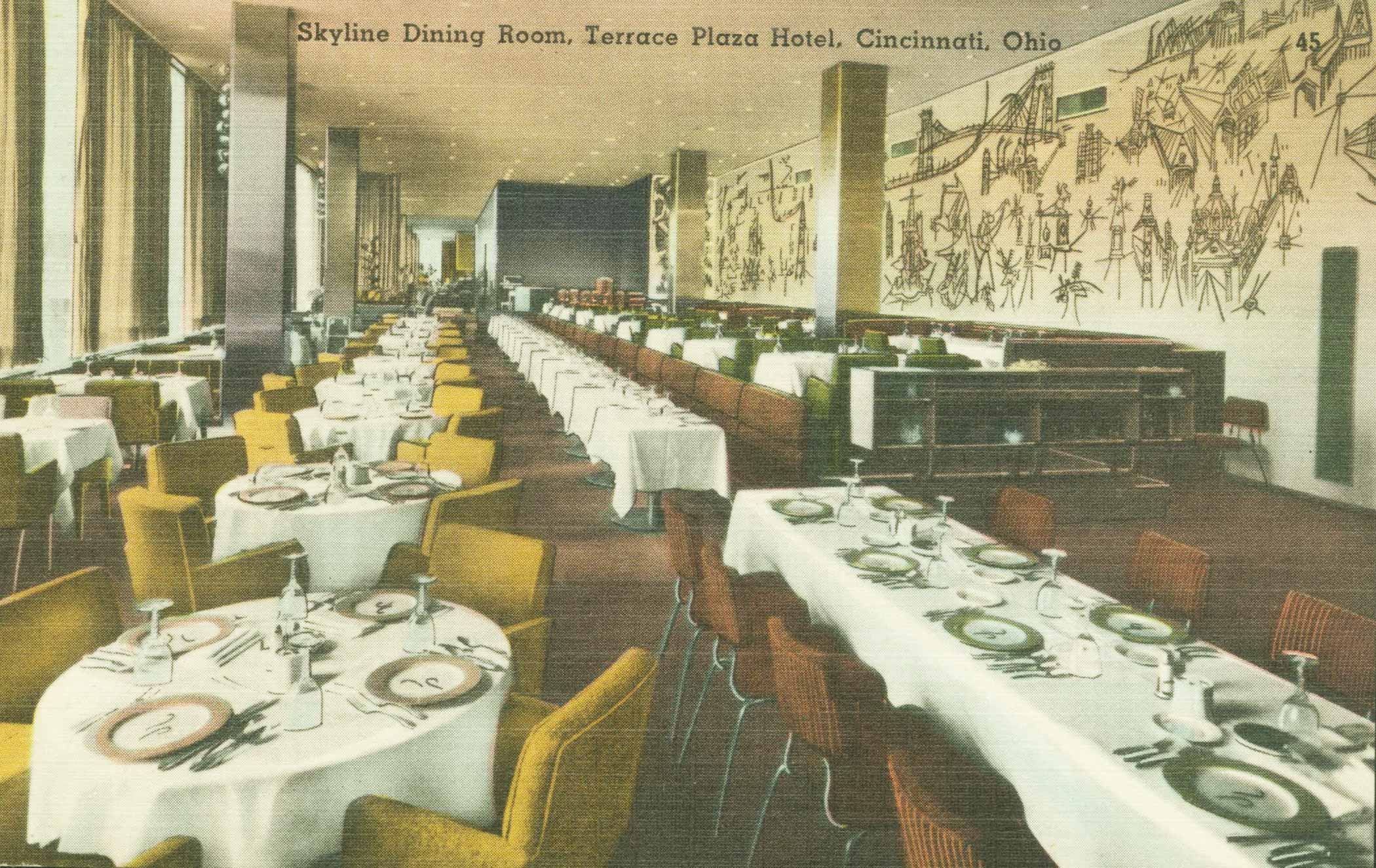

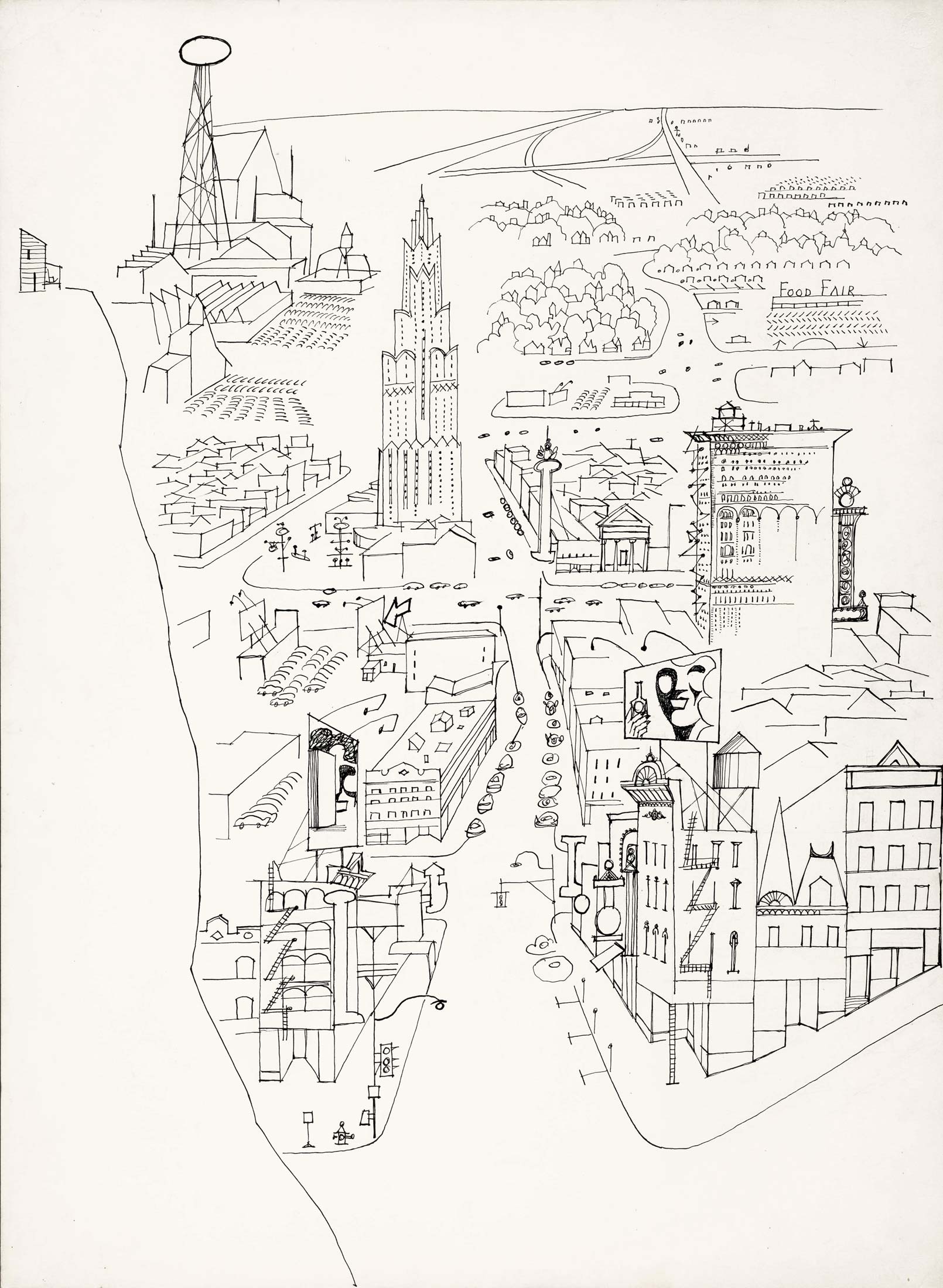

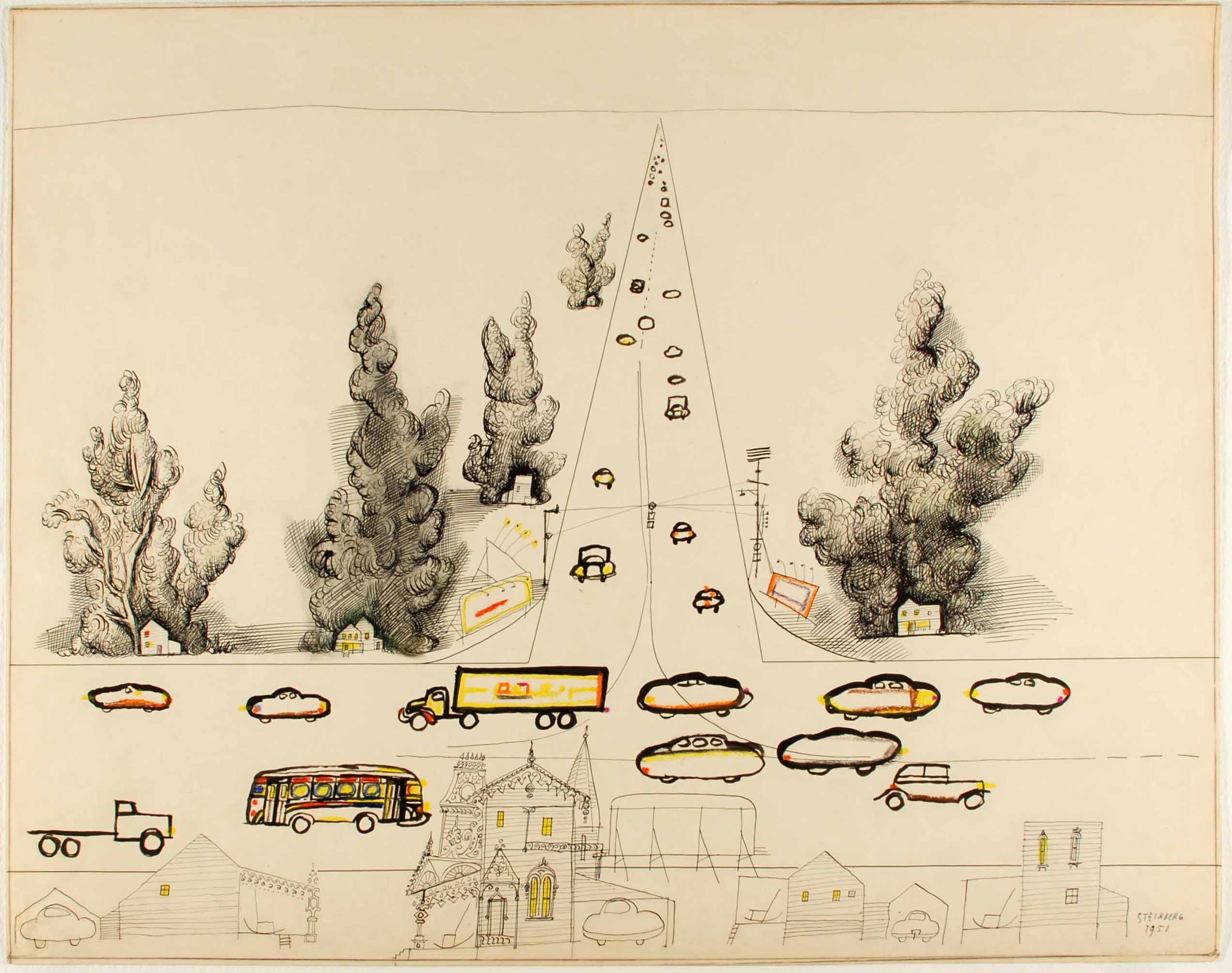

The second project, completed in 1948, was far more labor-intensive: an 89-foot mural of Cincinnati for the Skyline Room in the city’s new Terrace Plaza Hotel, the first International Style hotel in America, designed by Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill (the owners also commissioned a mural by Miró and a mobile by Calder). Steinberg executed the eight oil-on-canvas panels himself, rescuing the city and its inhabitants from a conventional panoramic view through an all-over composition that stacks elements on an upright plane; realistic proportions and perspectival logic have no place in this mural.25

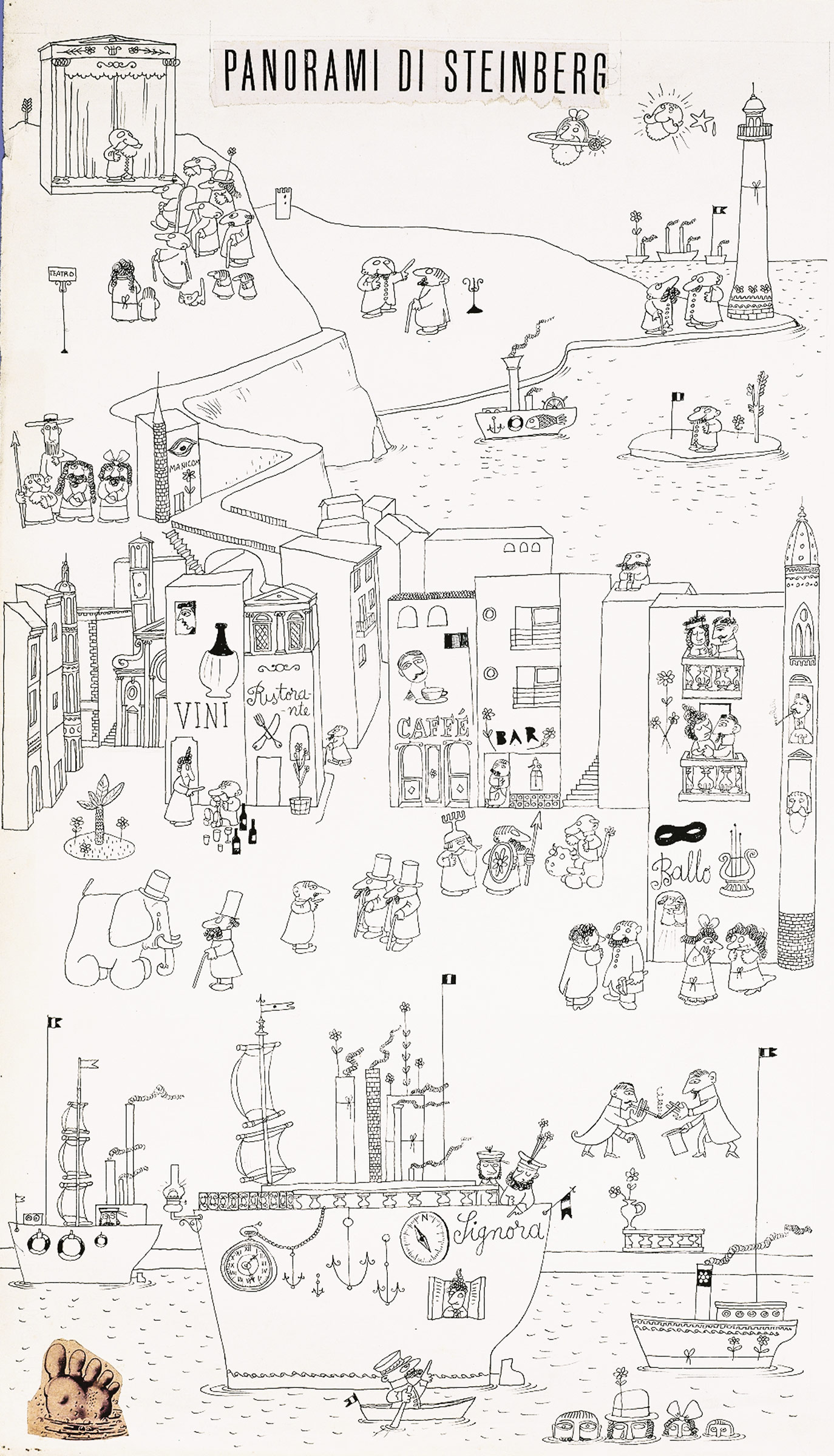

The system reminds us that there are always continuities and visual cross-overs in Steinberg’s art. The vertical stacking, which gave him more room to draw and became a common compositional resource, first appeared in his full-page “Panorami” drawings of the 1930s in Bertoldo.

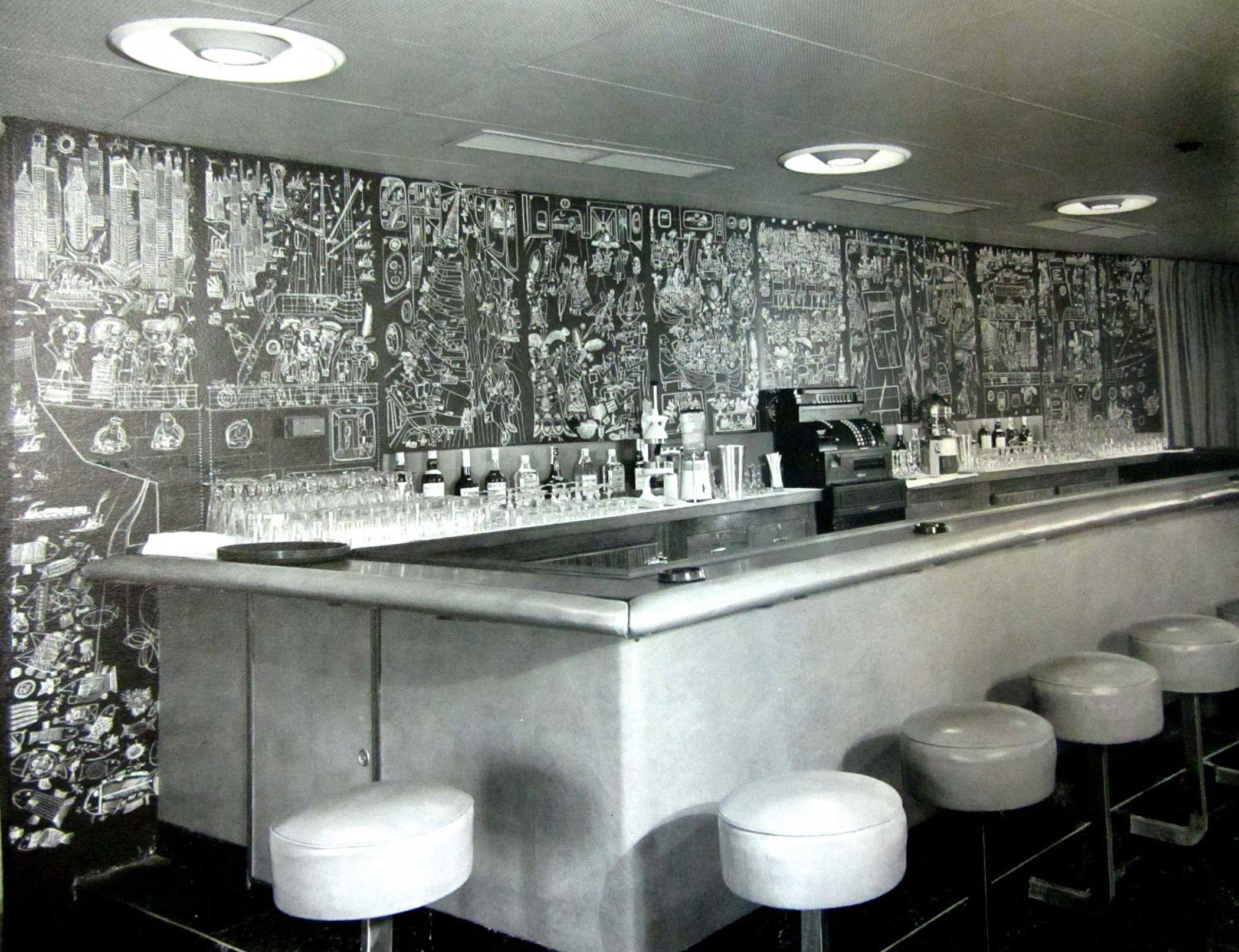

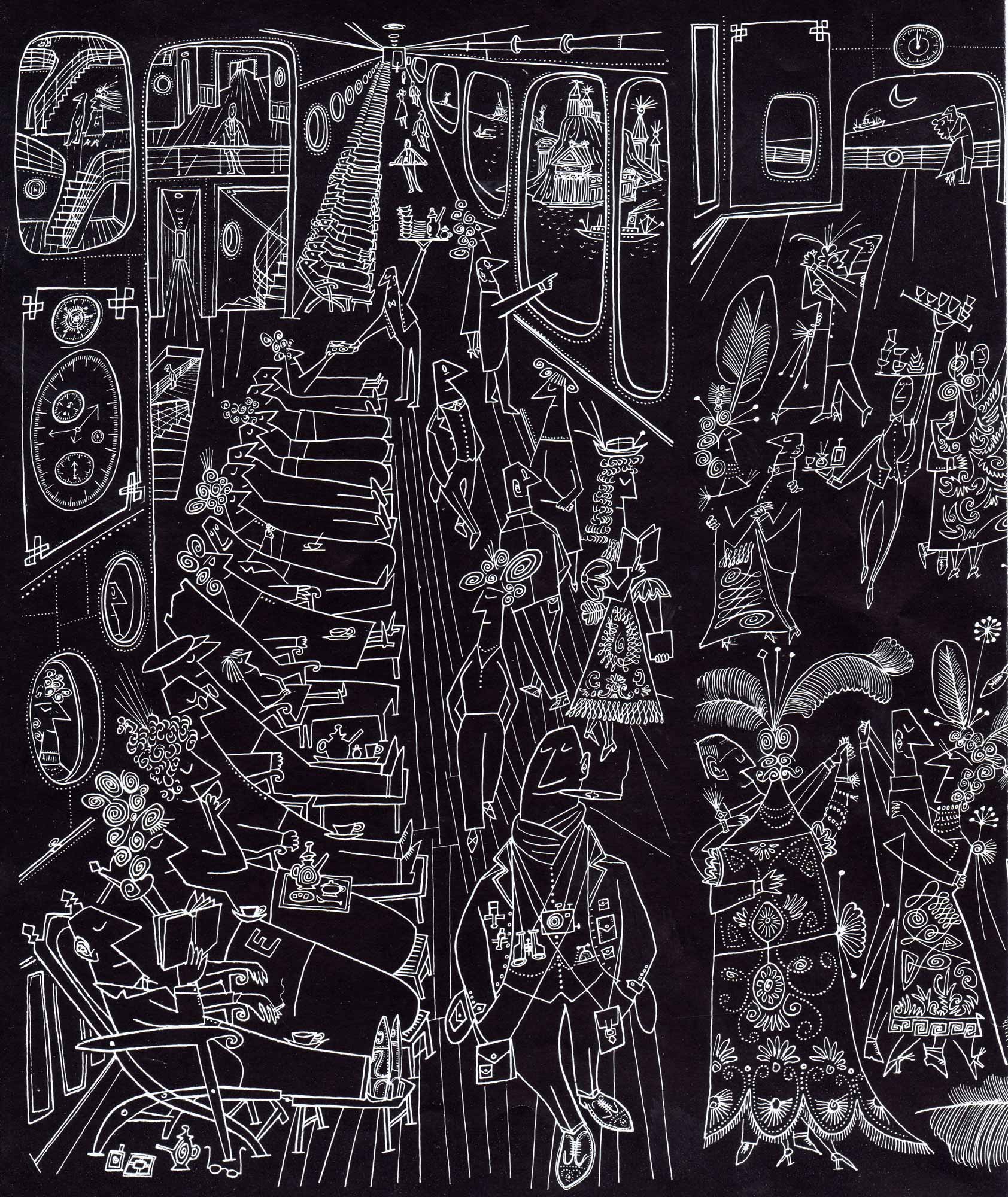

Exhausted by the Cincinnati project, Steinberg hit upon a labor-saving solution. As Joel Smith put it, he “decided to treat the wall like a printed page,” by submitting drawings which were then photographically enlarged. In his next commission, a mural for the bars in the “Four Aces” ships of the American Export Lines (1948), the photographs were printed in negative on Varlar, a new stain-resistant vinyl material. The eleven panels, again with raised horizons, began at left with the ship’s departure from New York Harbor and proceeded to entertain the barflies on each of the four ships with amusing vignettes of life at sea.26

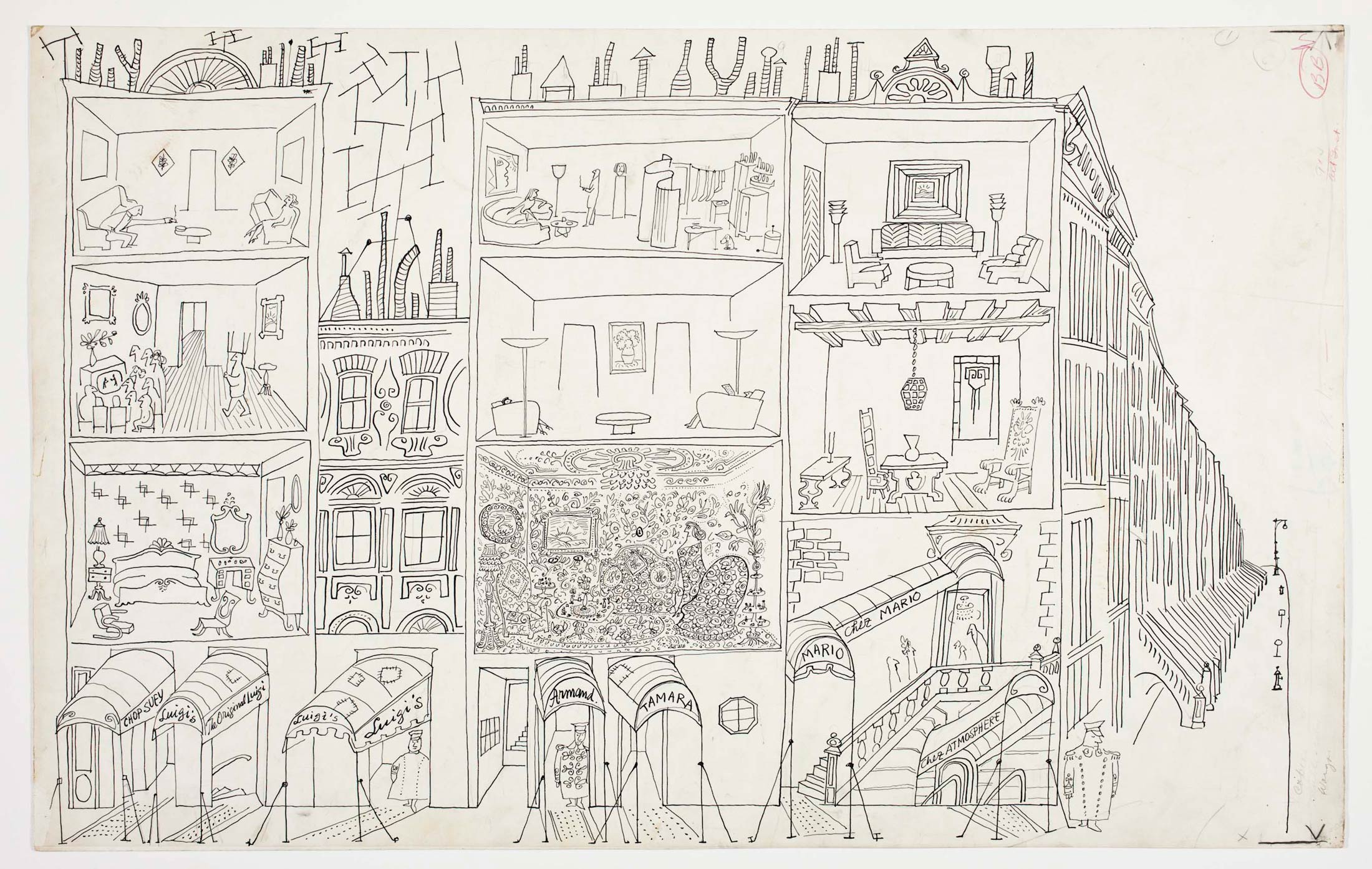

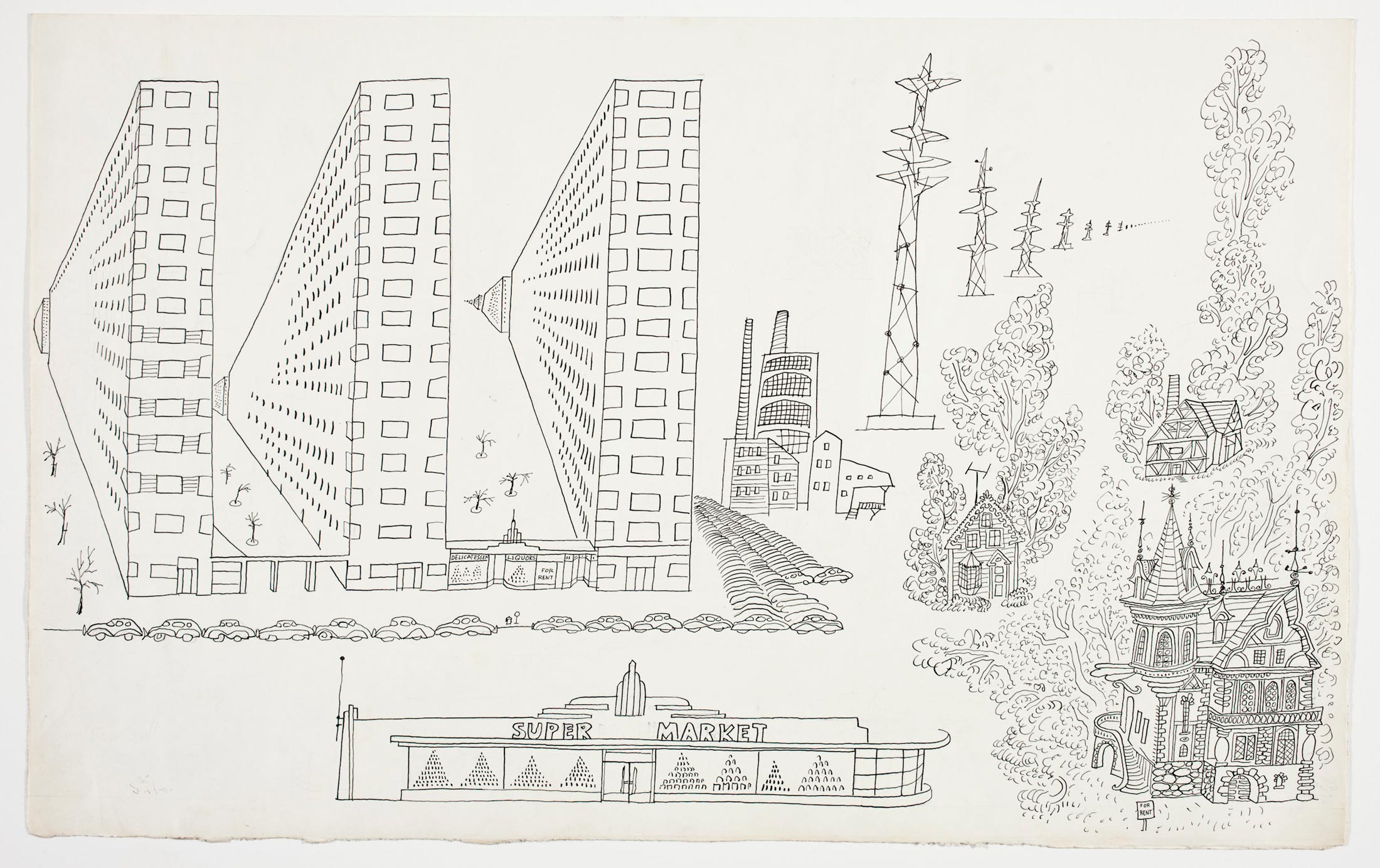

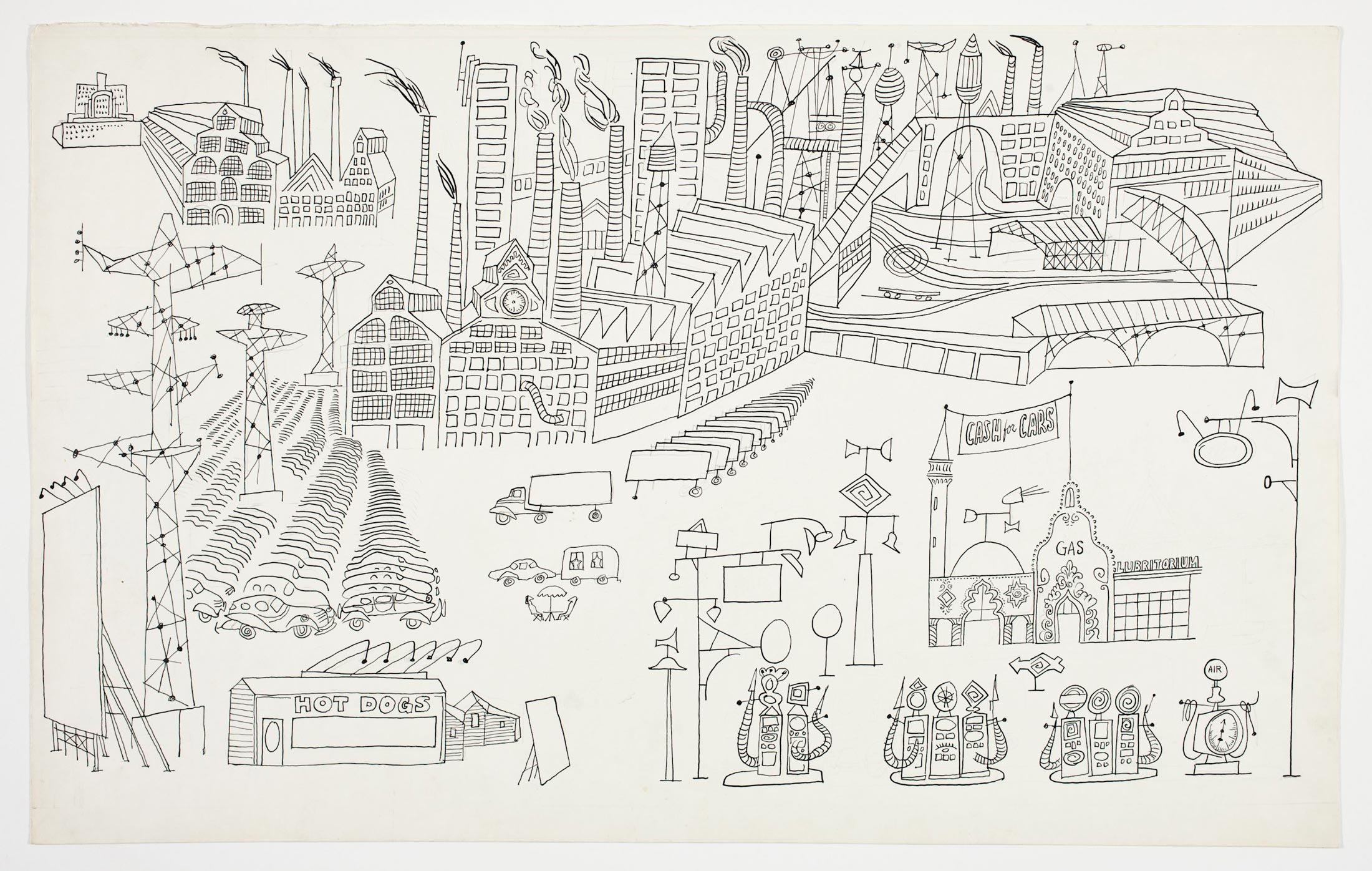

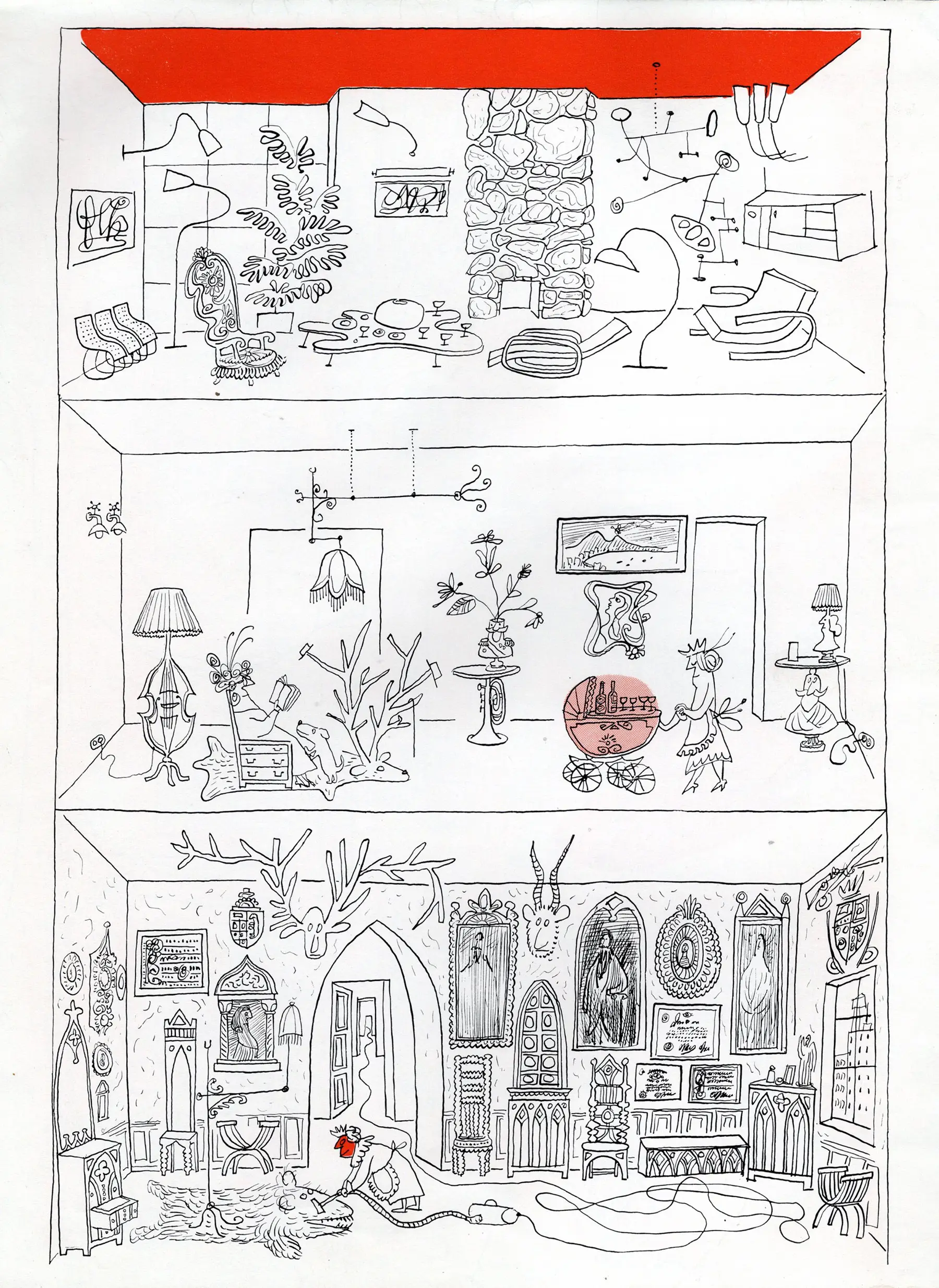

Steinberg employed the same technique—drawings photographically enlarged and applied to the walls—in a 1949 mural of the city of Detroit for Alexander Girard’s landmark show of modernist interior design and appliances, “An Exhibition for Modern Living”; only the drawings survive. Sponsored by the J.L. Hudson department store and installed at The Detroit Institute of Arts, the show plotted a common cause for art, industry, and new design; its two hundred exhibitors ranged from Charles and Ray Eames and Florence Knoll to Alexander Calder and Mark Tobey. Steinberg explained his role: “The architects are showing the good things that have been done…in the last twenty years. And I show…the ugly or stupid things that have been done.” Giant photographic lineshots of his drawings, touched with color following his specifications, portrayed Detroit’s industry and architecture, with some apartment houses in cutaway view, its interiors stocked with such necessities of life as aerodynamic toasters and antimacassar-draped Eames chairs. The exhibition sealed Steinberg’s identity within design and architecture circles as the draftsman-laureate of modernism.27

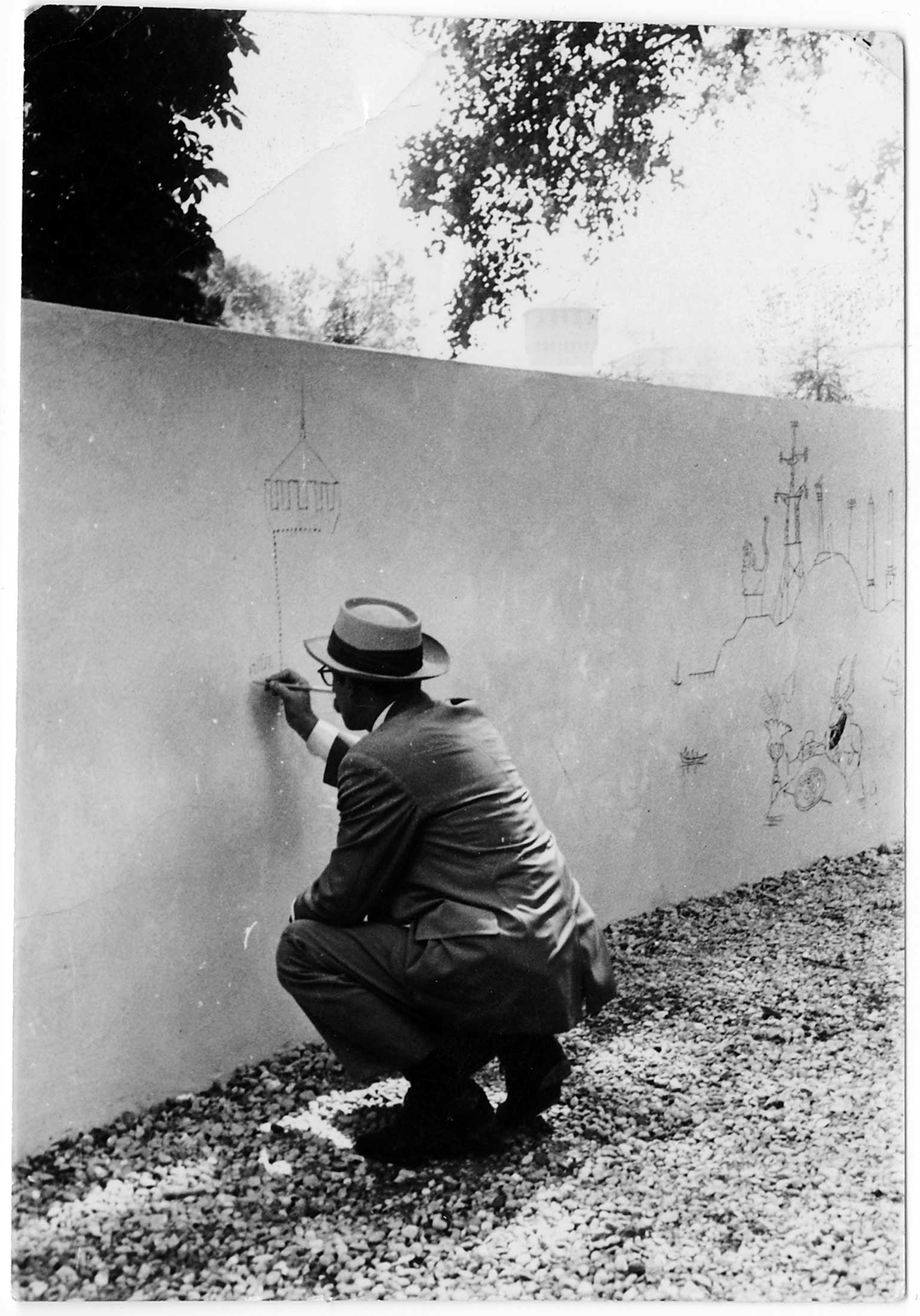

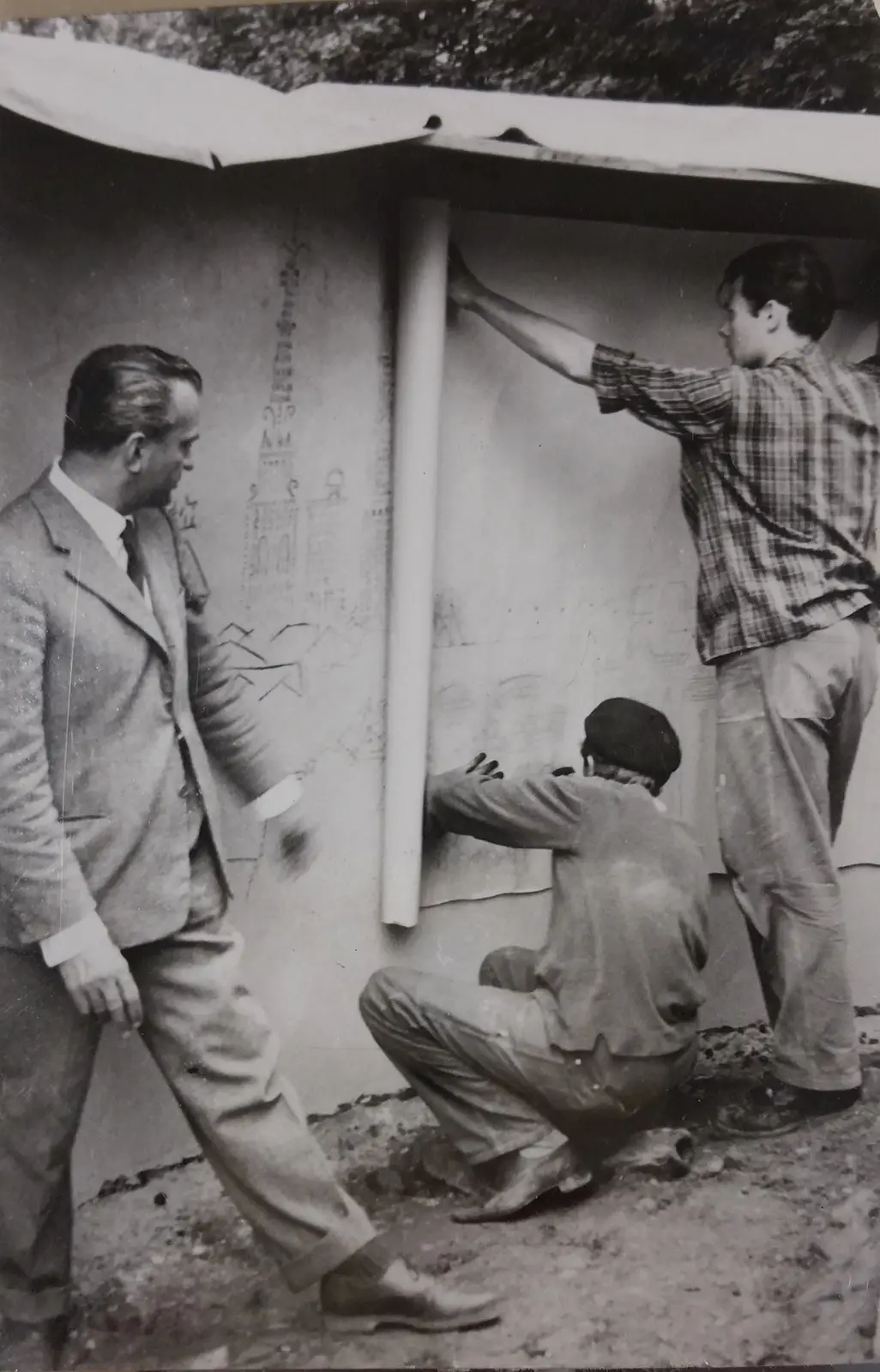

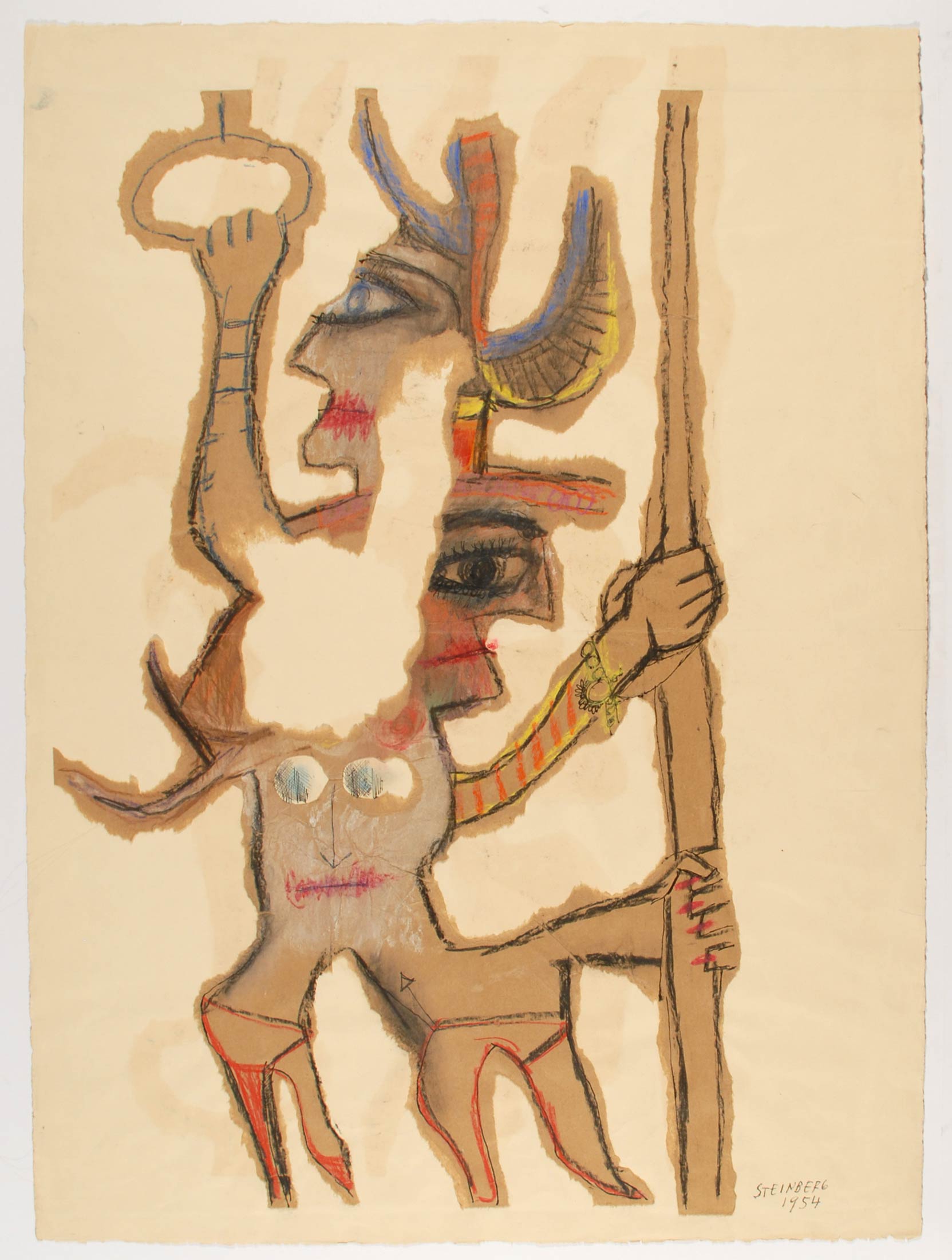

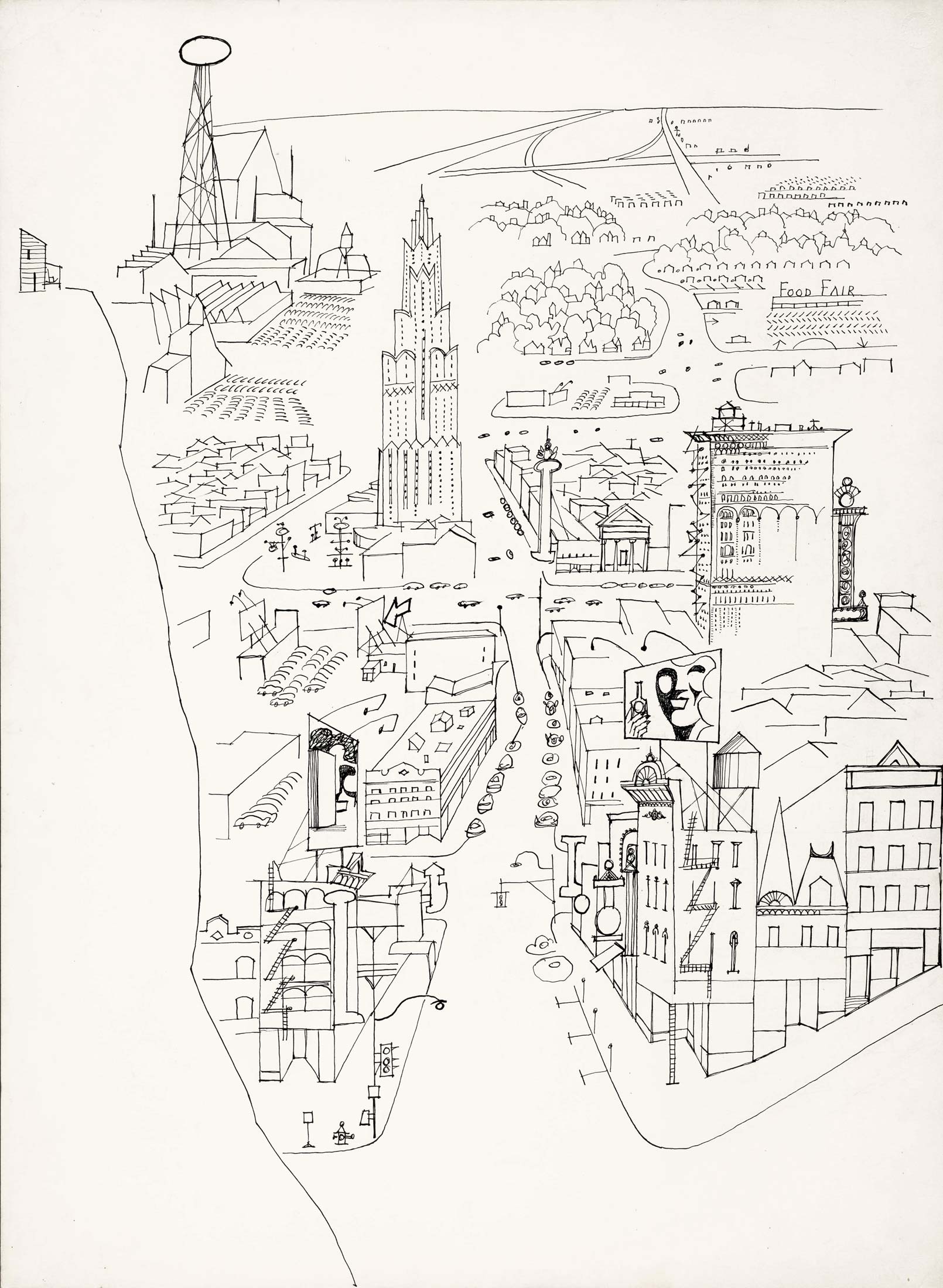

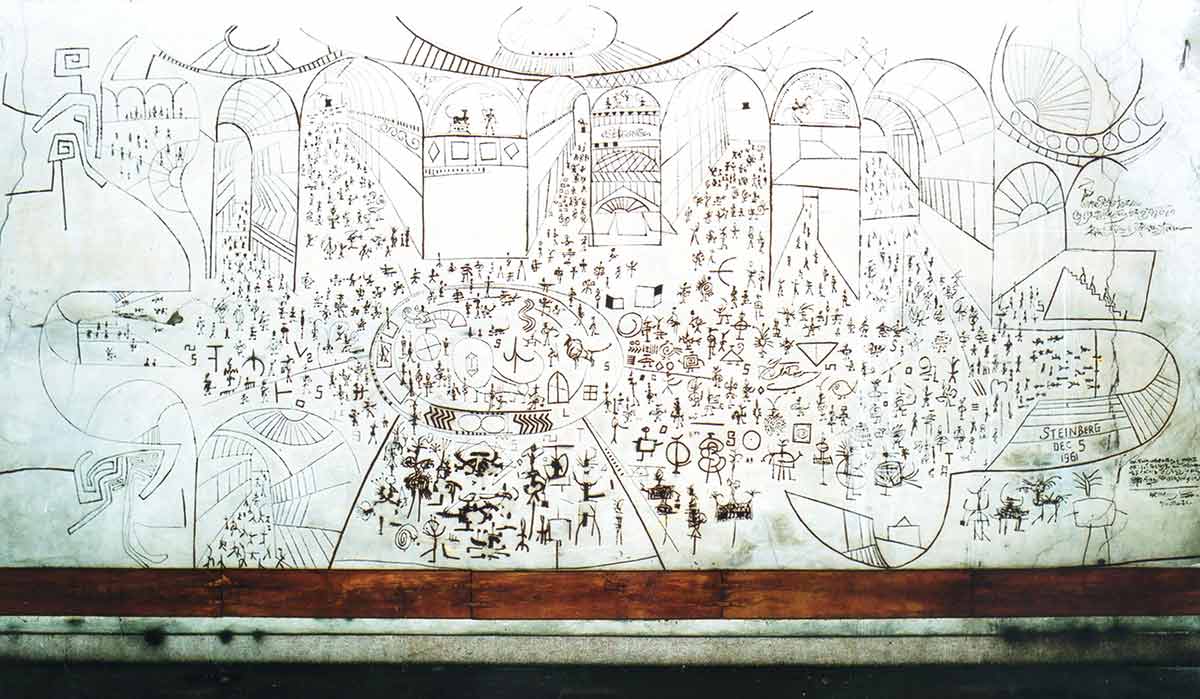

From these same architecture and design circles came his next mural commission, this one by way of friendships he had made in Milan in the 1930s. In 1954, for the 10th Milan Triennial, an architecture and design fair, Steinberg decorated the walls of the “Children’s Labyrinth,” a spiraling, trefoil wall structure with a Calder mobile at center.

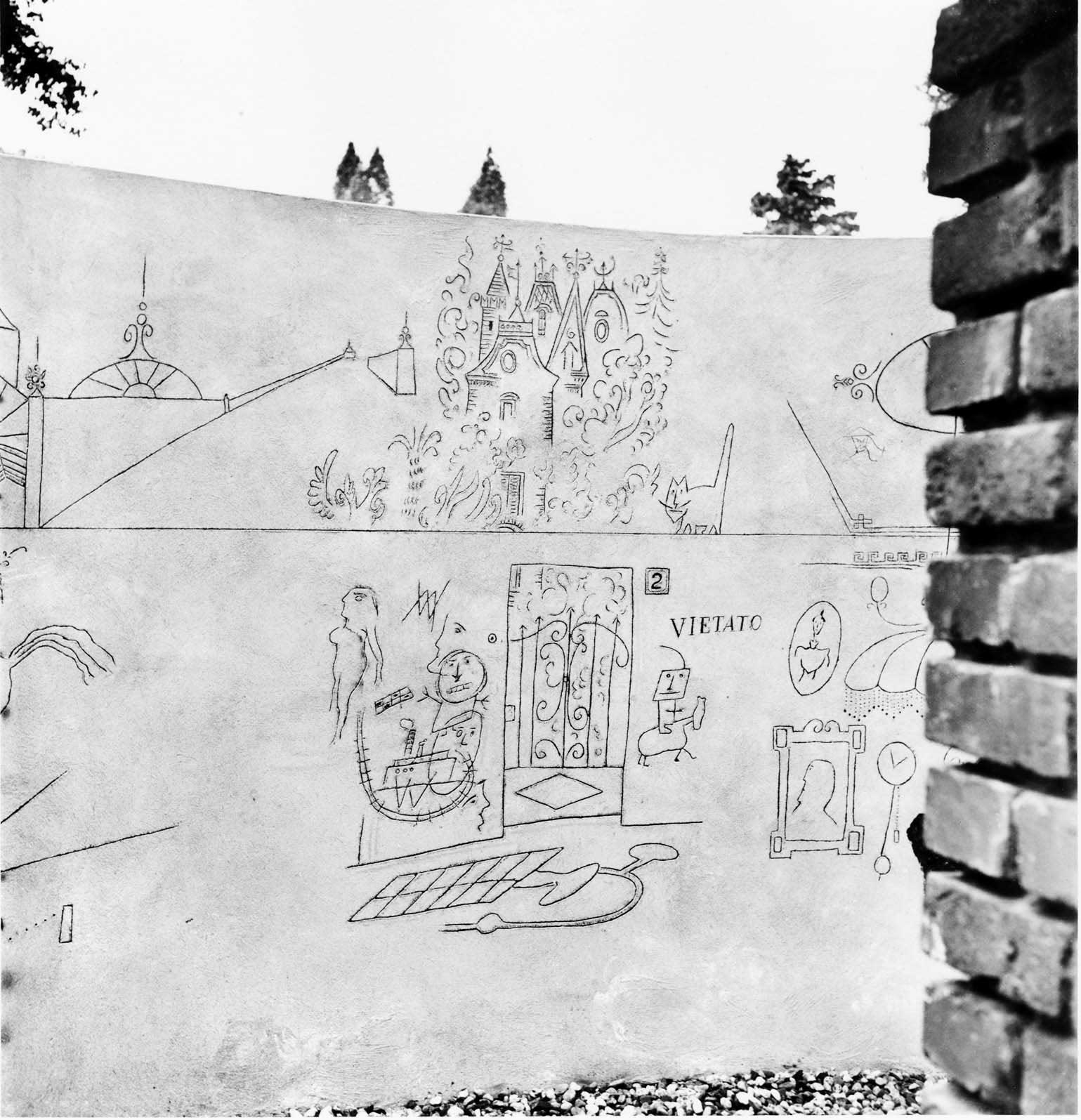

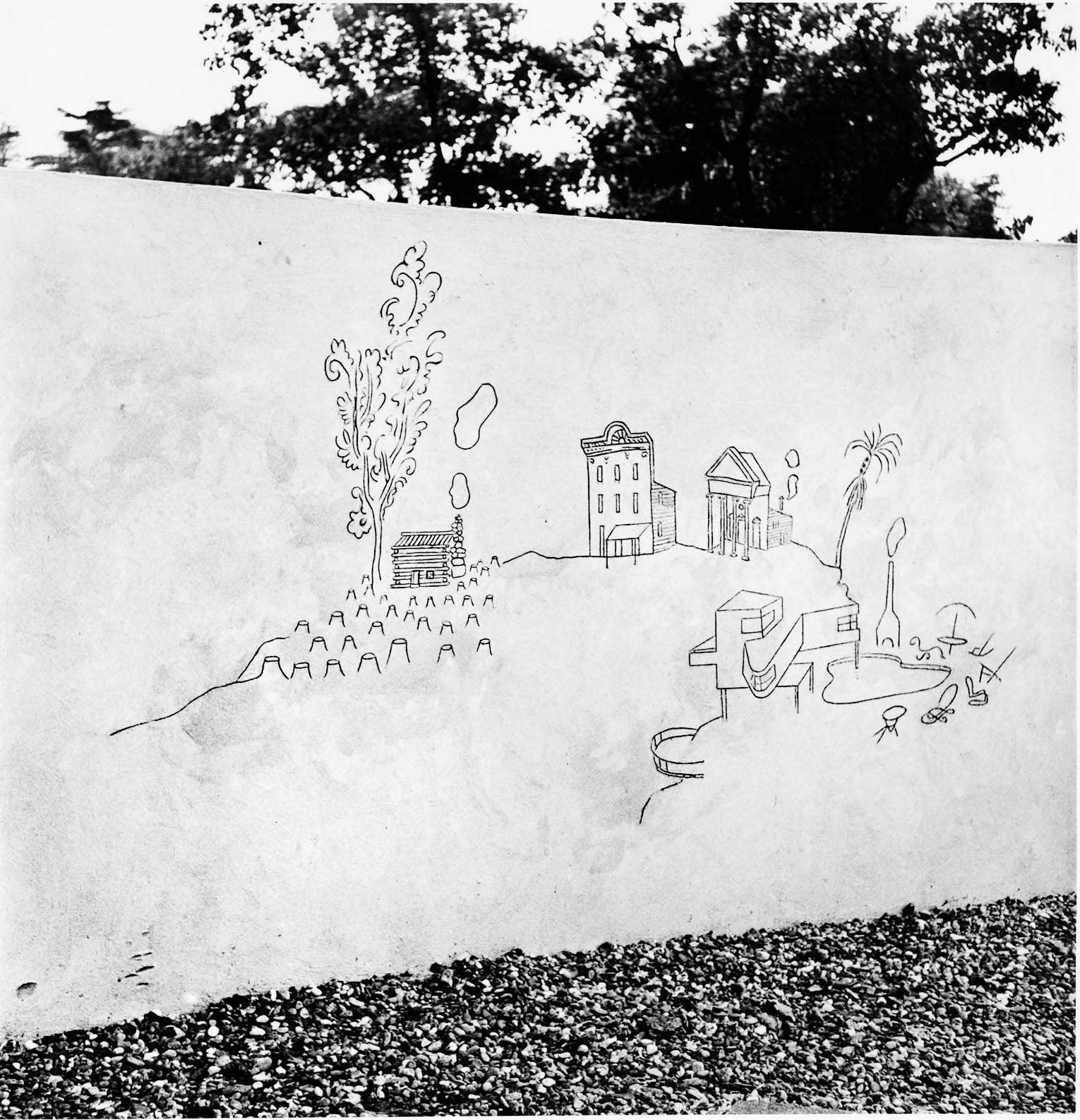

The commission came from the architectural firm of BBPR, two of whose partners, Enrico Peressutti and Ernesto Rogers, had known Steinberg in his Politecnico days. In a variation on his production process, the drawings were photographically enlarged and then incised into the walls in a sgraffito technique, most of the work done by a band of assistants, though Steinberg occasionally picked up the cutting tool himself to fill in gaps.

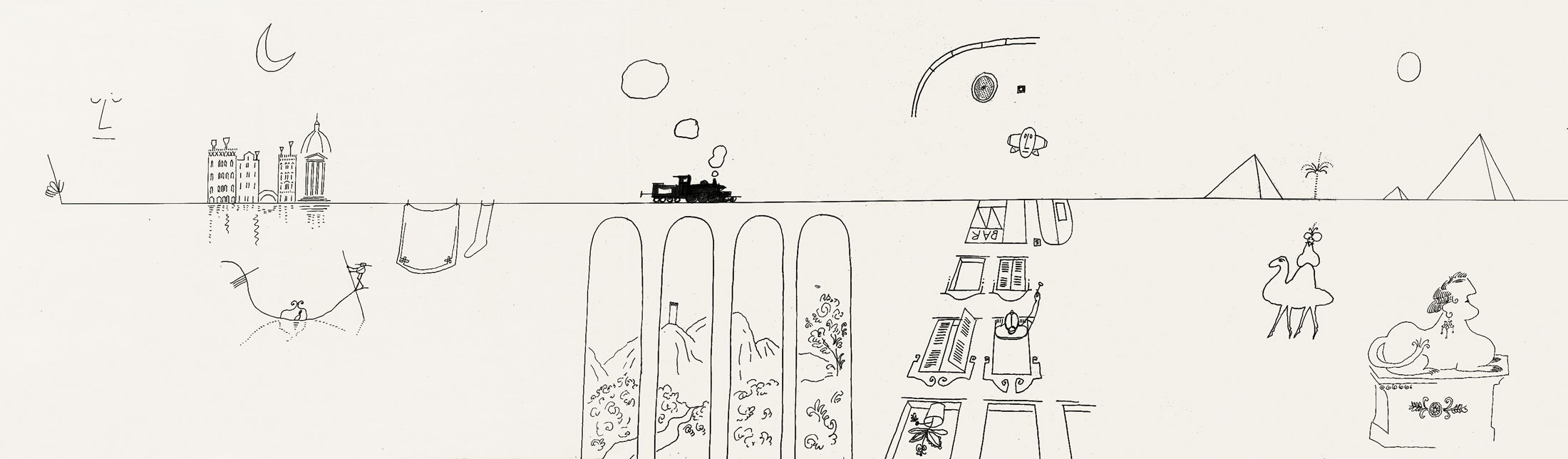

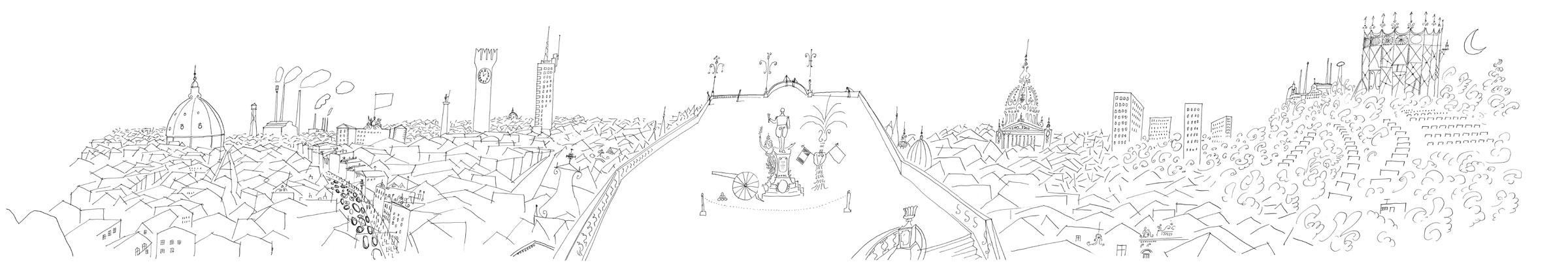

Although the structure was demolished at the close of the Triennial, Steinberg’s four long drawings survive. The Line, which begins and ends with a hand drawing, is Steinberg’s manifesto about the conceptual possibilities of the line, as a single horizontal line shifts meaning from one passage to the next—water line, laundry line, railroad track, among many others—commenting on its own transformative nature.28

Types of Architecture is a satirical survey of world architecture, from America’s log cabins to Bauhaus exaggerations to fragile skyscrapers.

Shores of the Mediterranean presents a sailor’s-eye-view of the Mediterranean coastline, filled with the ruins and renascences of successive civilizations.

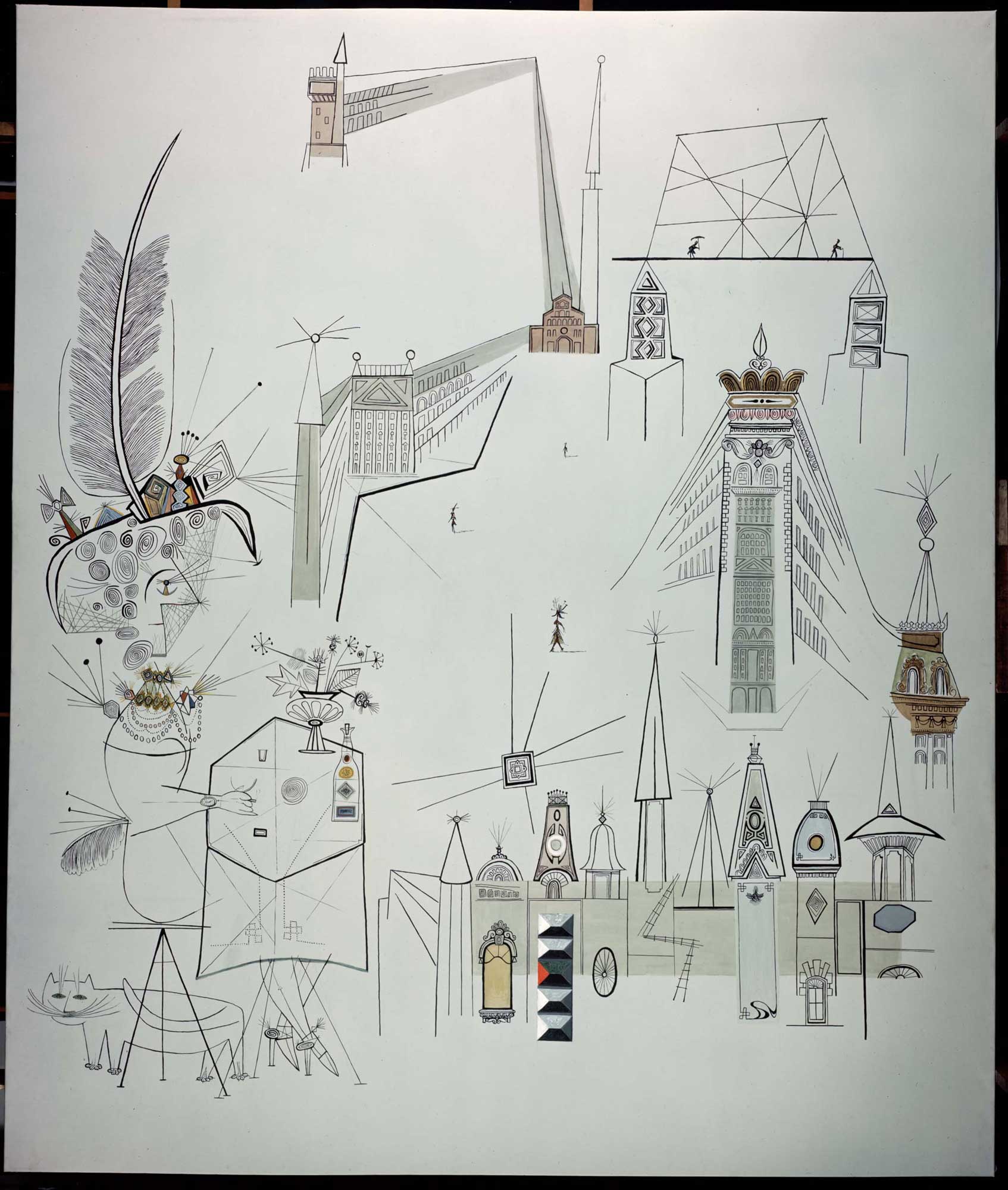

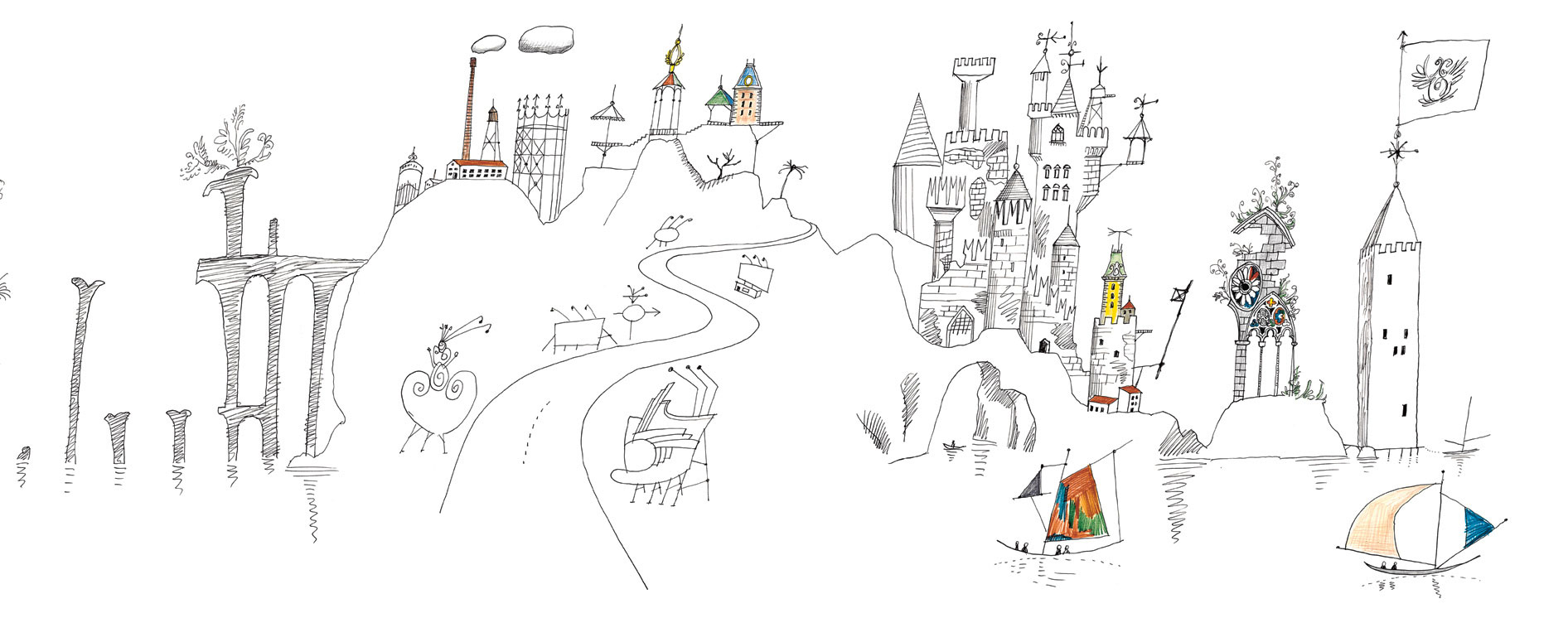

The Italy Steinberg knew as a student in the 1930s resonates in Cities of Italy, as the inked line imagines an urban sprawl of campaniles, factories, piazzas, apartment houses, curlicued domes, and a gas tower that seems to have escaped from a carnival.29

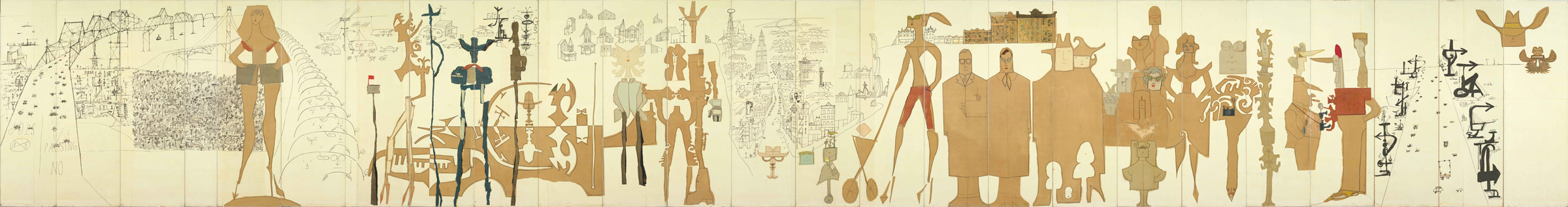

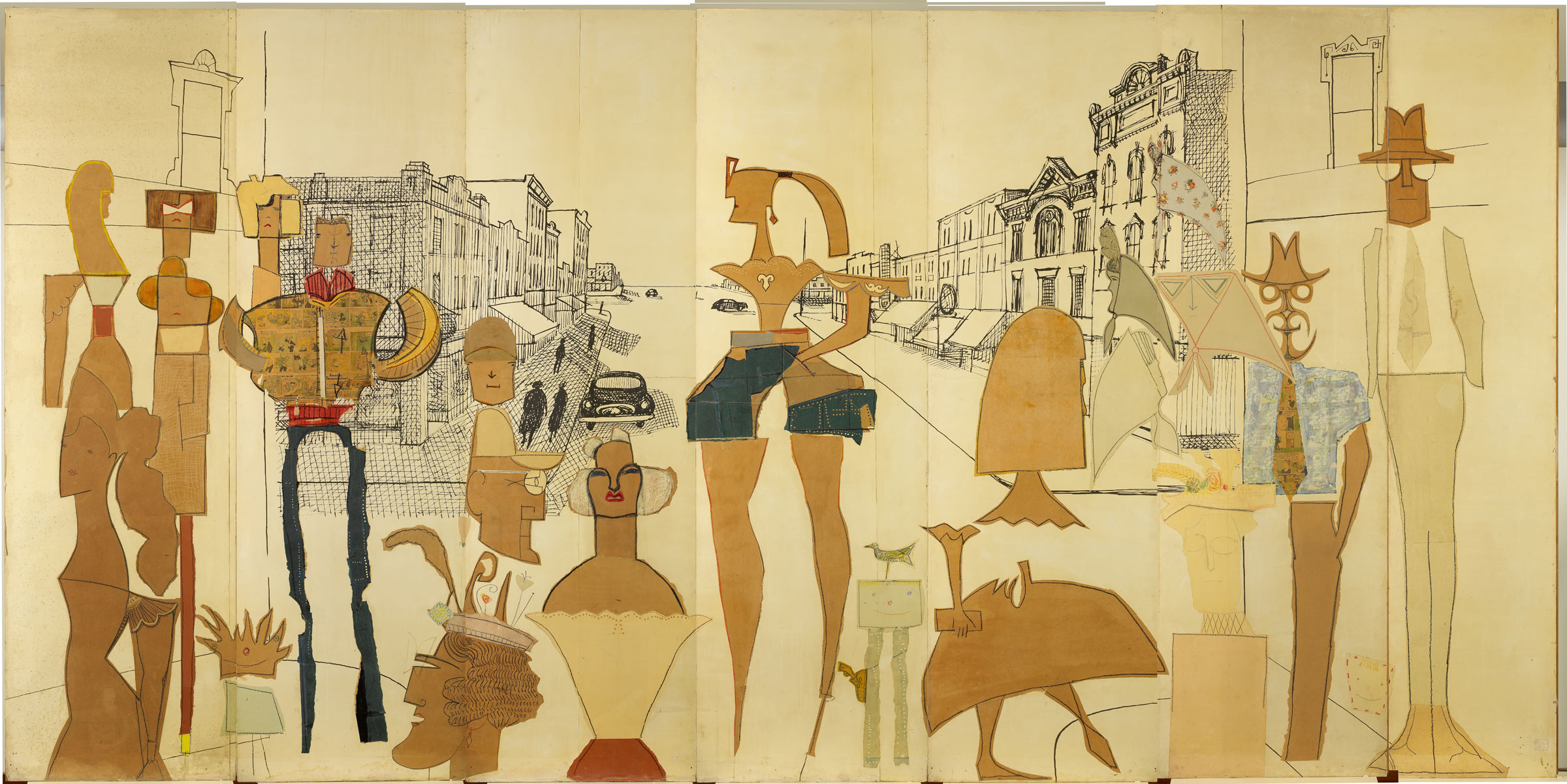

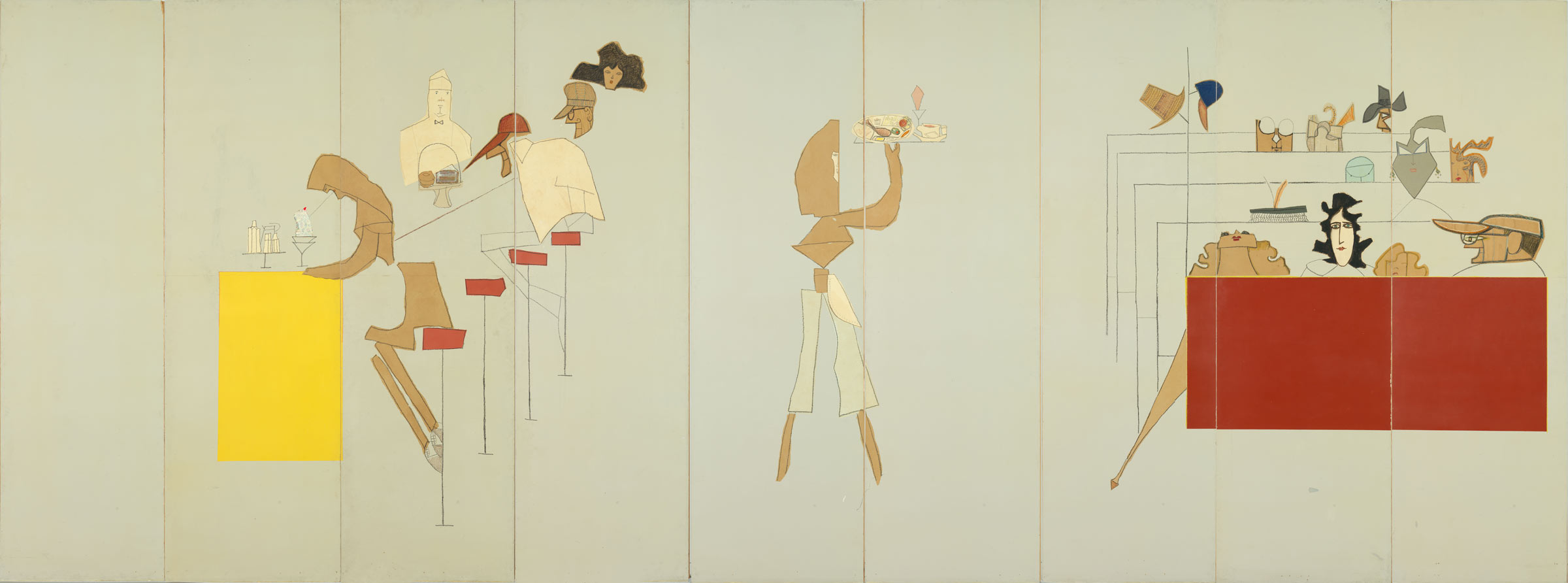

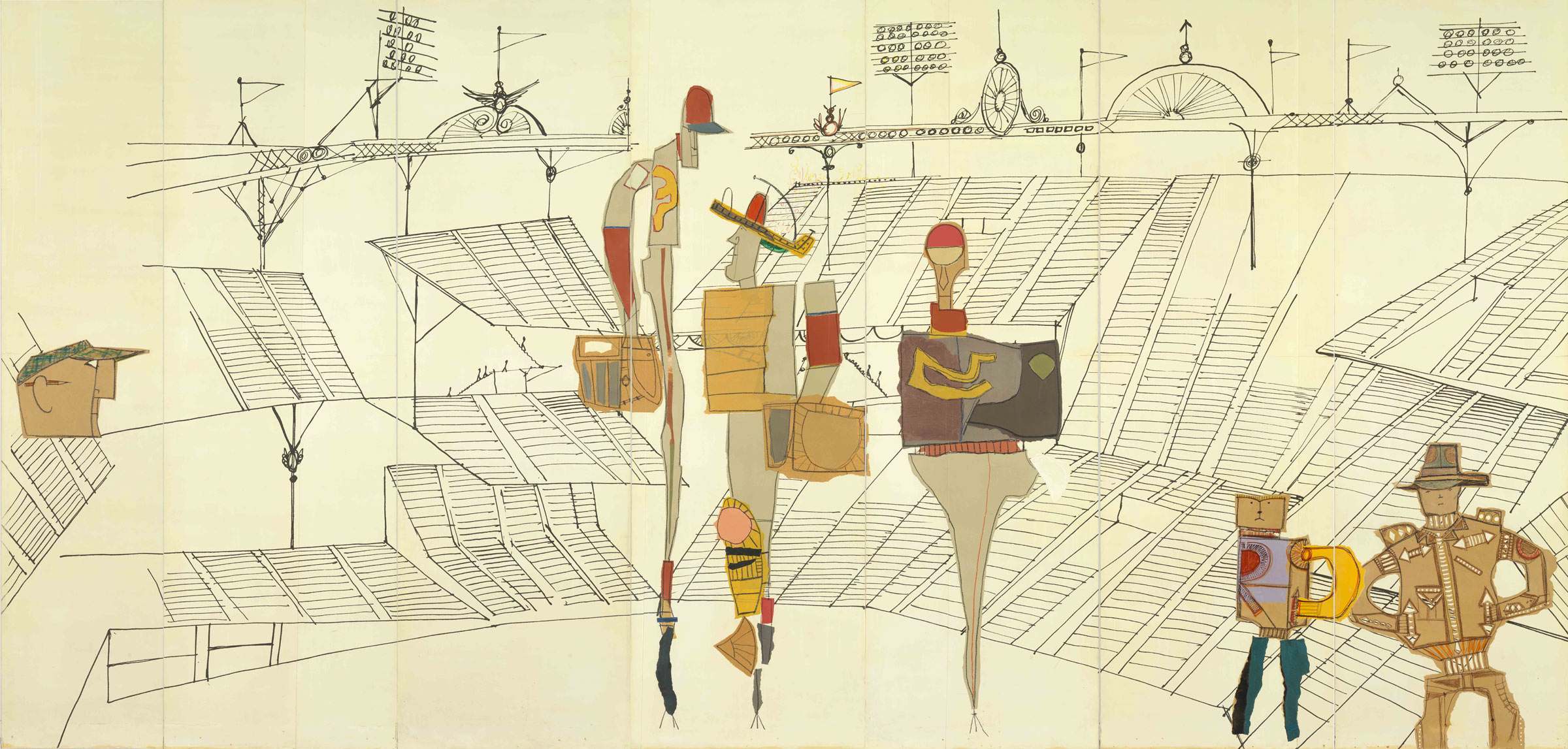

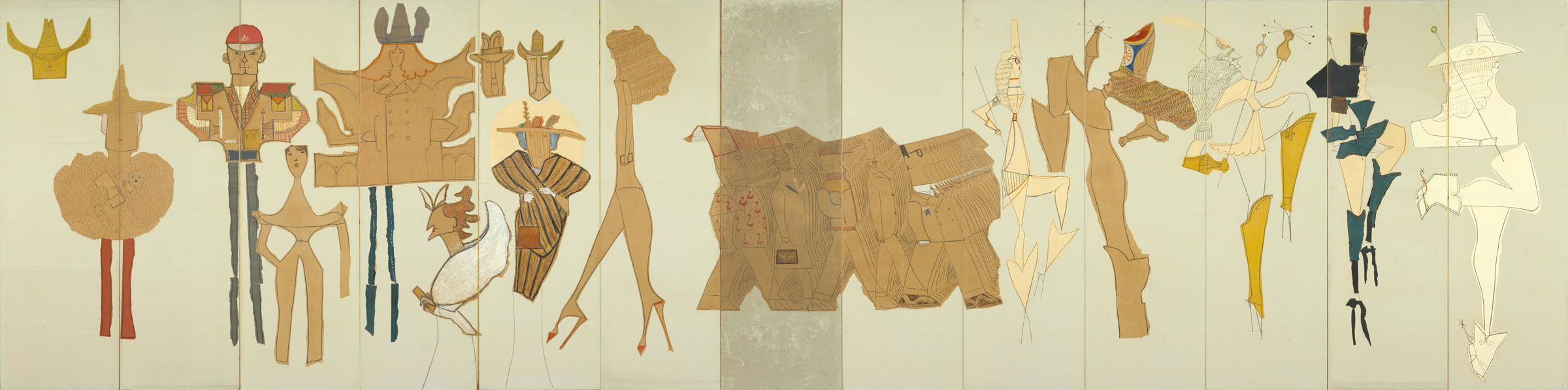

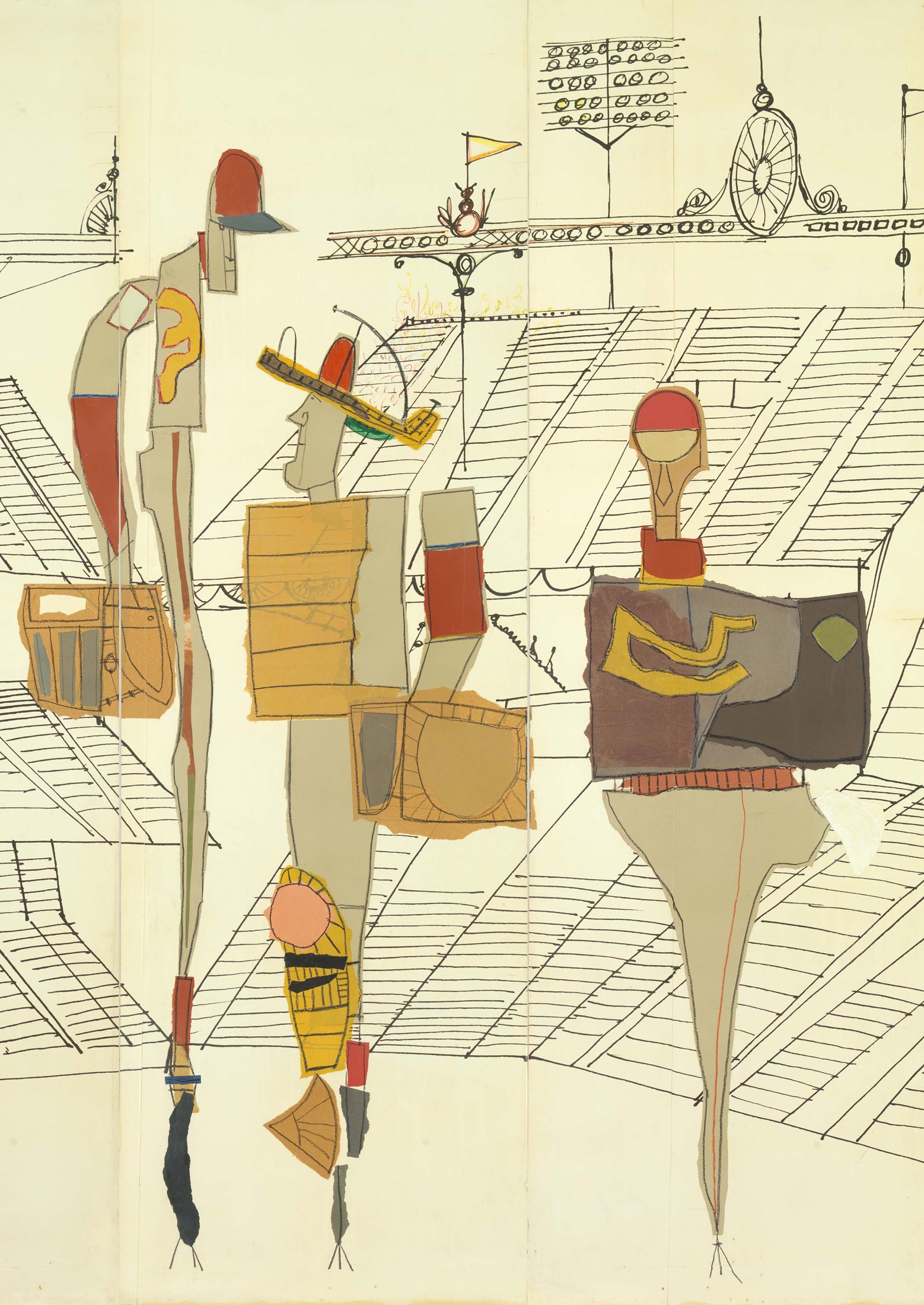

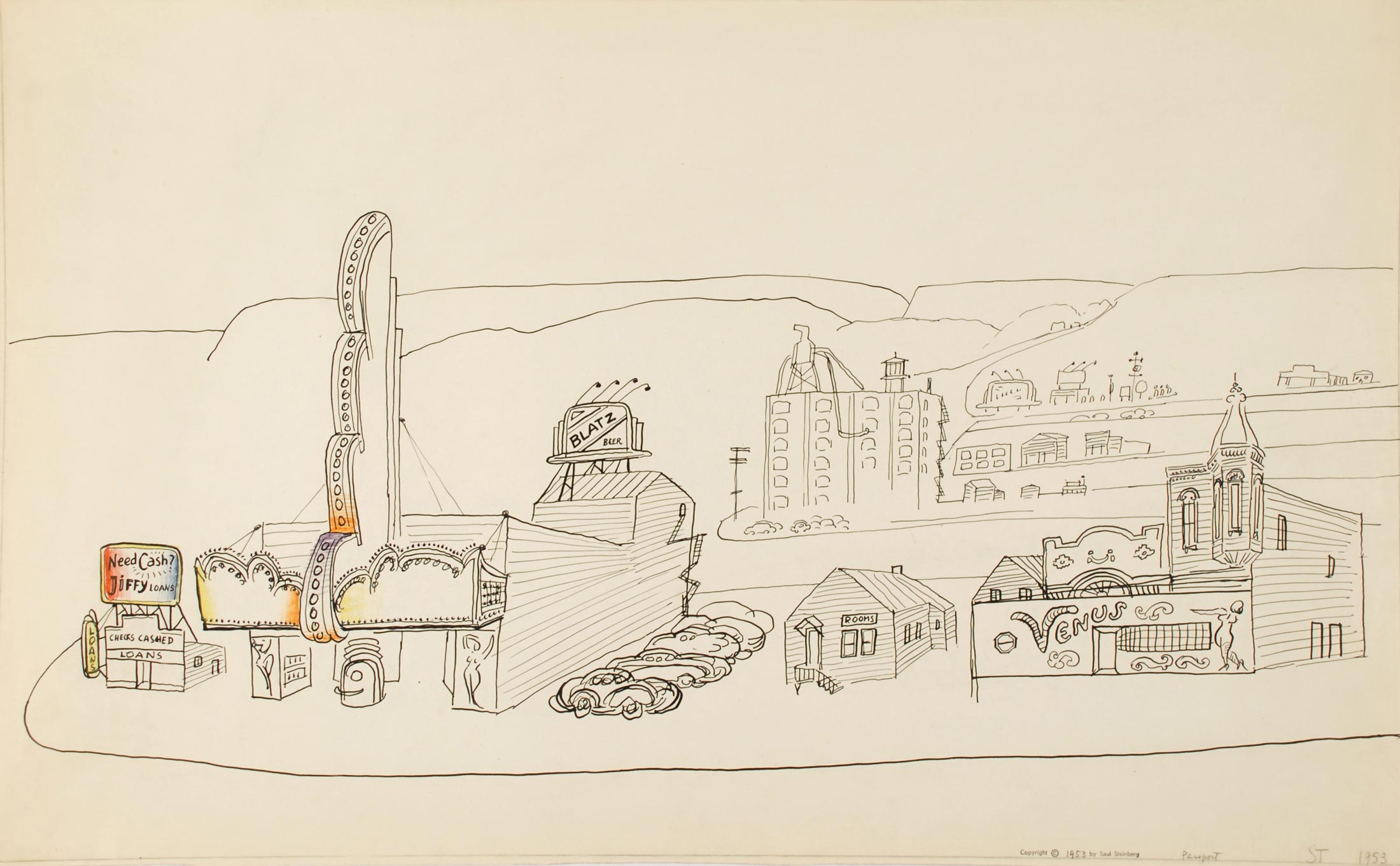

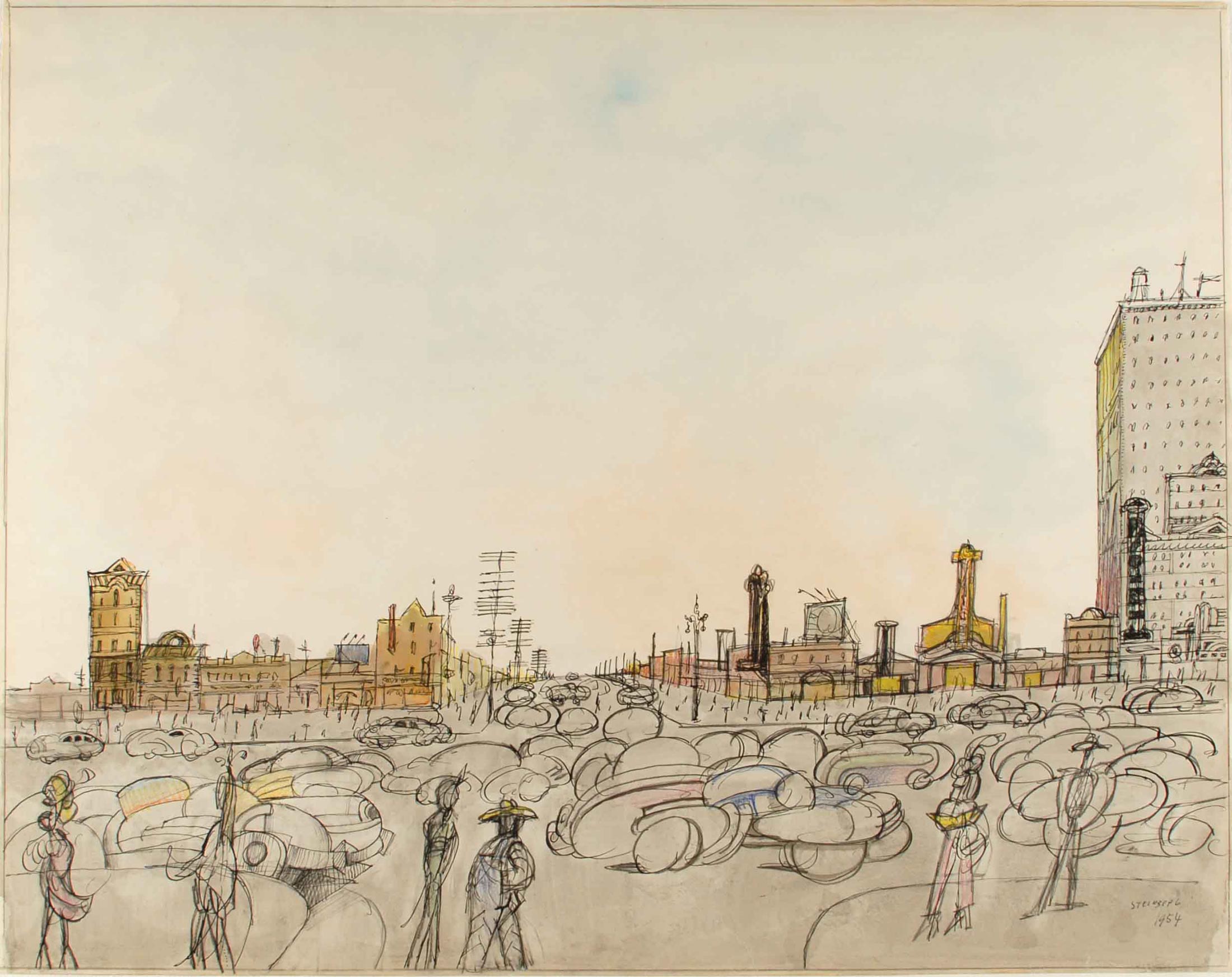

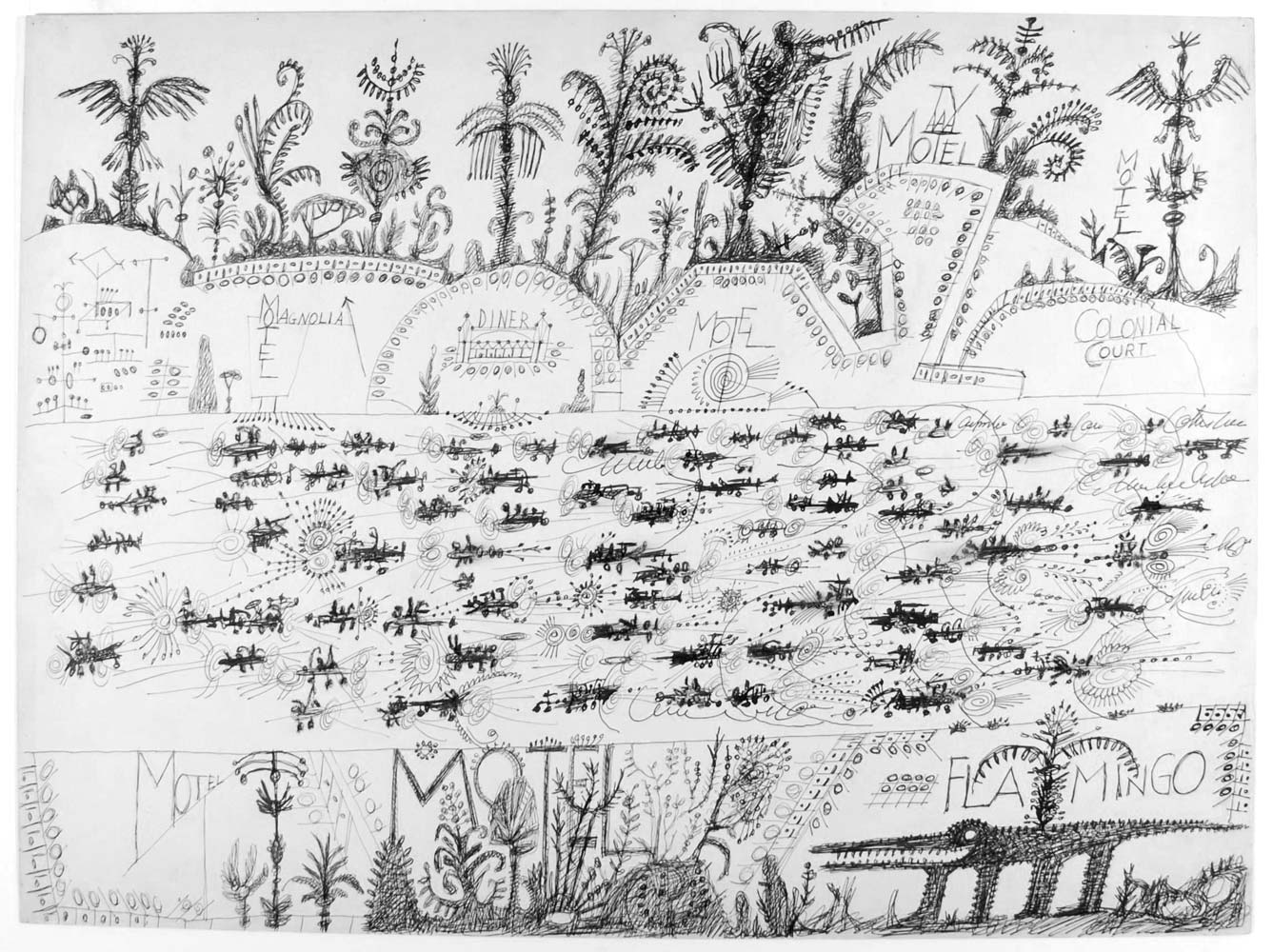

Steinberg’s last major mural commission is his most extraordinary—a colossal mural-collage entitled The Americans, made for the US Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Ten feet high with a total length of more than 240 feet, it was divided into eight thematic sections: Downtown—Big City; The Road—South and West; Main Street—Small Town; Cocktail Party; Drugstore—Small Town; Baseball; California, Florida and Texas; Farmers—Middle West.

Steinberg supplied background drawings of the locales, which were photographically enlarged onto freestanding walls.

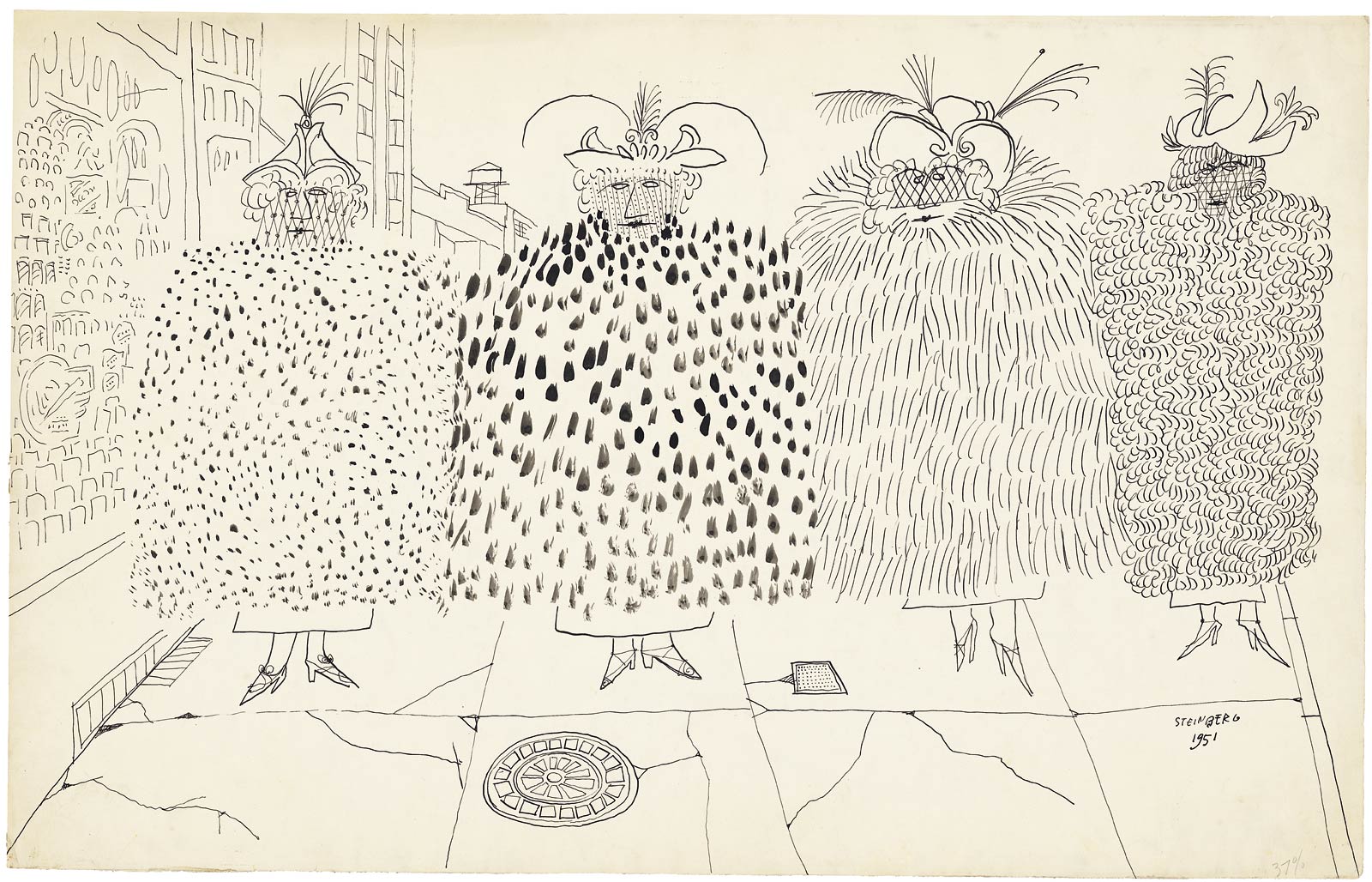

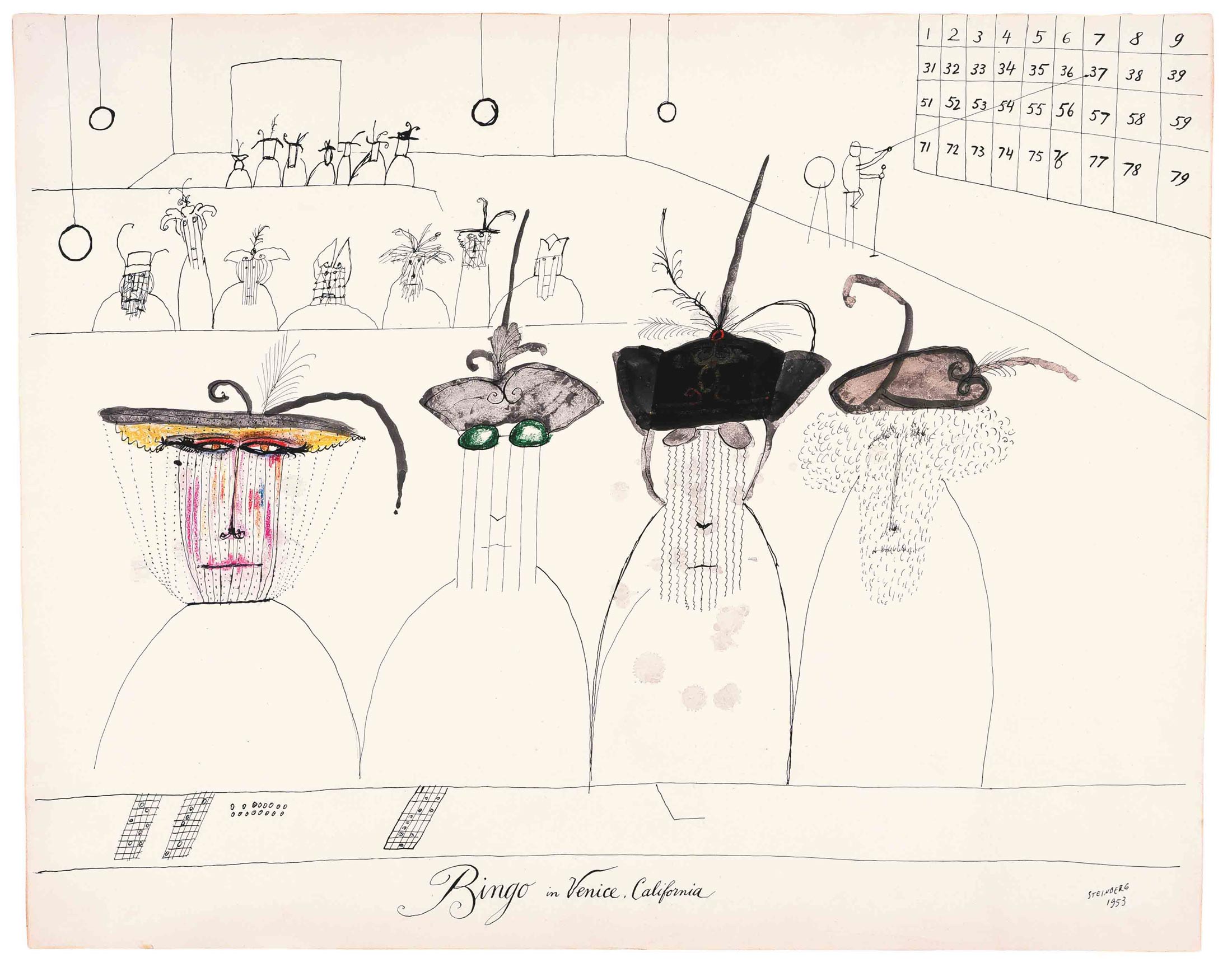

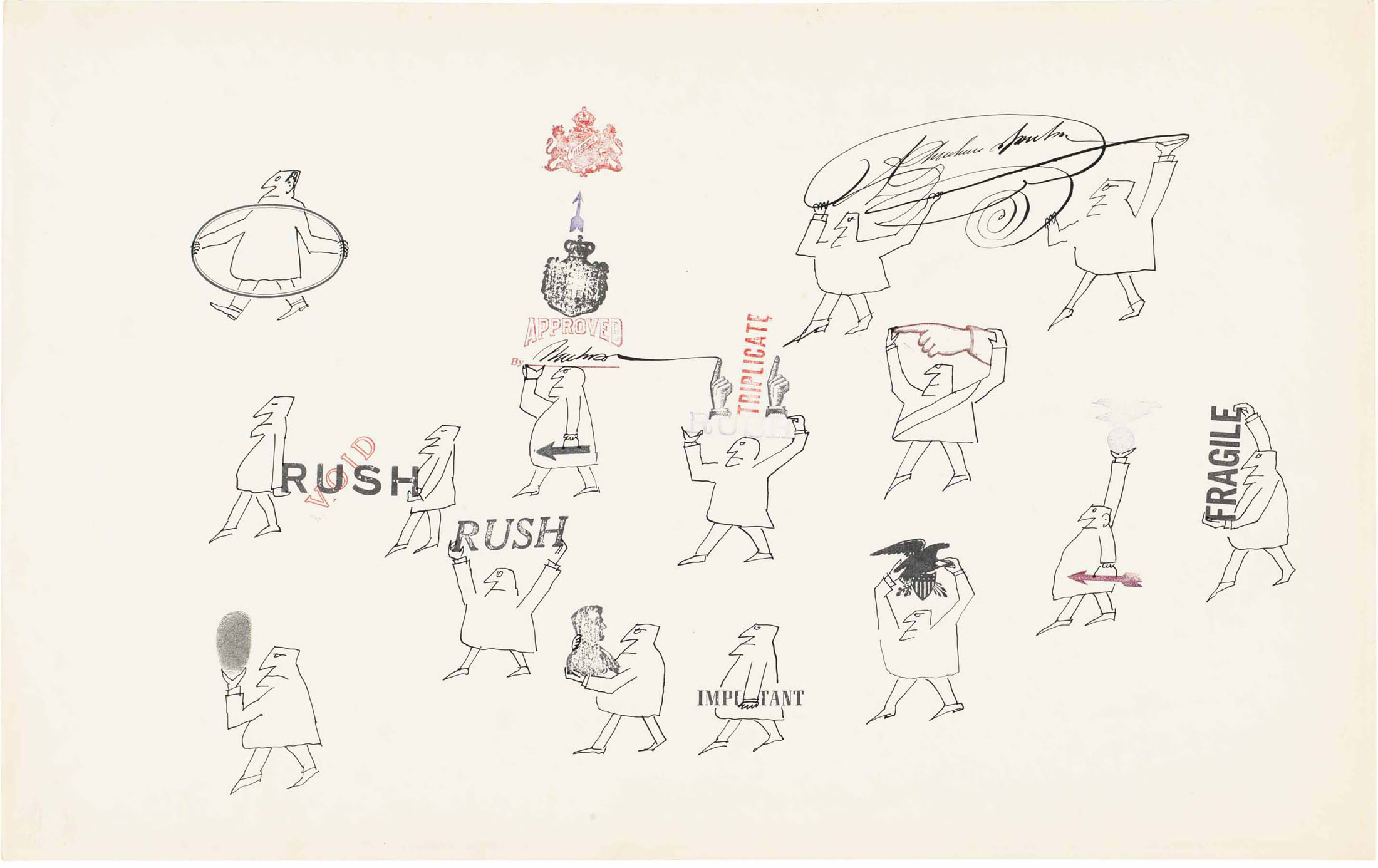

But, in a departure from his usual practice, he then spent more than three weeks on site, adding brown-paper cutouts of American characters, their garments often fashioned from added collage elements—painted paper, fabric, wallpaper, and clippings from the Sunday comics. The murals present a panorama of everyday life in America, from the hustle-bustle of the big city to the ostensibly idyllic world of rural communities. An array of collaged human figures dominates the foregrounds, sometimes singly, sometimes densely packed. They testify to Steinberg’s assimilation of a wide range of artistic influences and to his creative application of a variety of media and materials, including drawing, photography, wallpaper, packing paper, and comics. His immigrant’s view of the American way of life is affectionately humorous, though not without a darker cast, as he registers the postwar automobile culture, urban development, corporate conformity, and a sociological sense of alienation.

The Americans is also deeply engaged with issues that resonated in the art world of the 1950s, from Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art to the faux-naïve style of Paul Klee and Jean Dubuffet. The mural’s monumental scale anticipates the billboard-size works of James Rosenquist, while the ragged, life-size cardboard cut-outs also seem to foreshadow Claes Oldenburg’s landmark installation of 1960, The Street. The reuse of popular imagery, such as comic strips for collage material, playfully calls into question the traditional borders of high and low art. In The Americans, such boundary-crossing, a mainstay of nearly all Steinberg’s art, resulted in a masterful integration that abetted clever social commentary.30 Not surprisingly, the gigantic Americans are kinfolk to the characters populating Steinberg’s smaller-scale works of the 1950s. With graphic styles adjusted to suit personas and places, Steinberg caricatured a nation, exposing the excesses of fashion, egos, lifestyles, and the changing American scene.

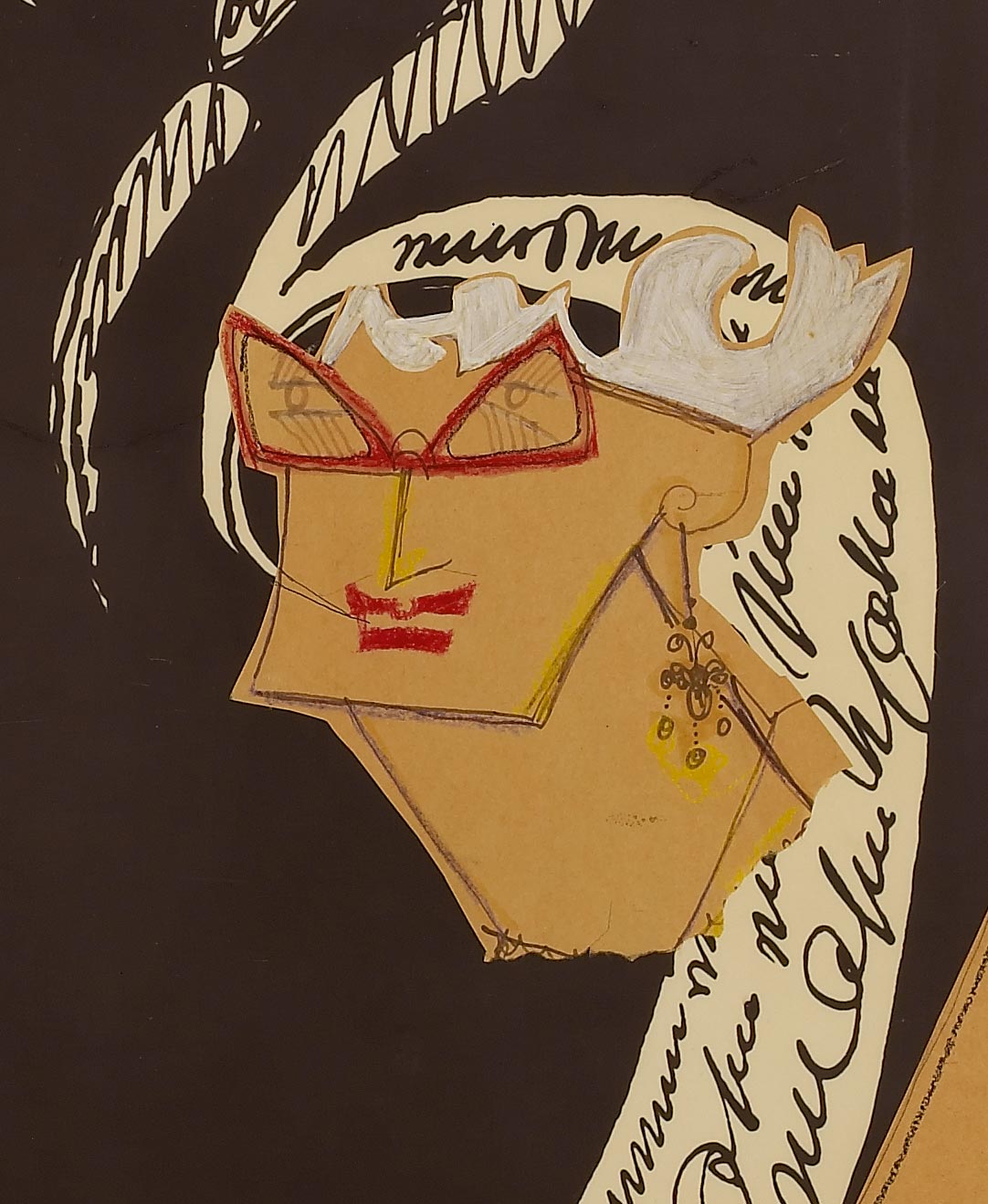

![<em>Untitled [At the Racetrack]</em>, c. 1958. Ink, crayon, and watercolor on paper, 14 ½ x 23 in. The Saul Steinberg Foundation.](https://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/128.-SSF-347-SM.-c.-58.jpg)

![<em>Untitled [Florida Types]</em>, 1952. Ink and collage on paper, 30 x 24 in. The Art Institute of Chicago; Gift of The Saul Steinberg Foundation.](https://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/130.-SSF-1960-C-028-SM.-52.jpg)

![<em>Untitled [At the Racetrack]</em>, c. 1958. Ink and colored pencil on paper, 14 ½ x 23 in. National Gallery of Art, Prague; Gift of The Saul Steinberg Foundation.](https://saulsteinbergfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/133.-SSF-308-C.-58.jpg)

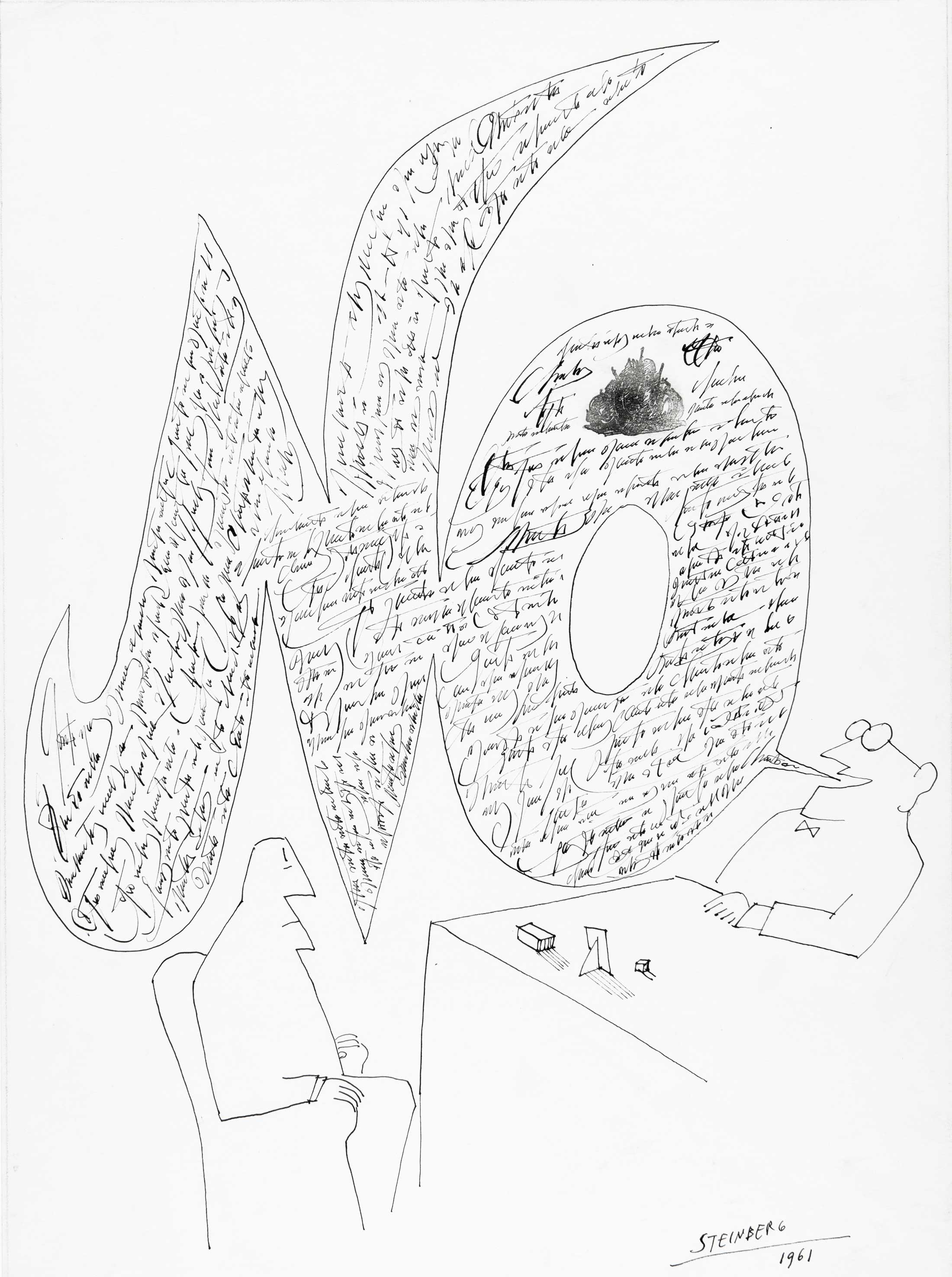

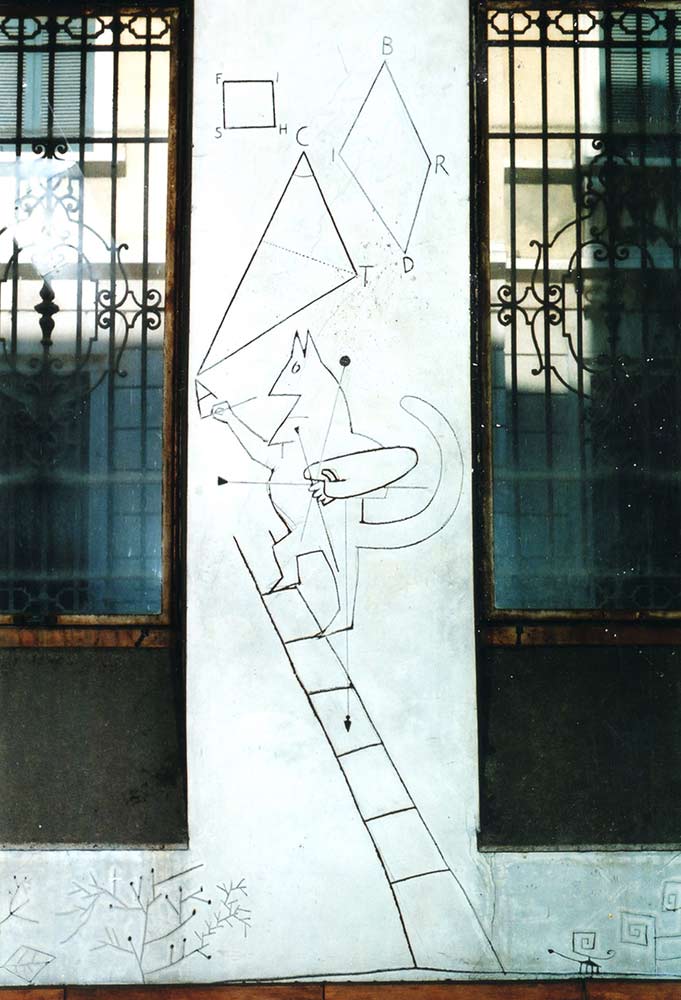

Steinberg accepted one private mural commission in 1961, for the entryway of the Palazzina Mayer on via Bigli in Milan. The commission came through the architectural firm of BBPR, which had also commissioned the “Children’s Labyrinth” for the 1954 Milan Triennale. Like that work, the Palazzina Mayer mural was done in the sgrafitto technique, but this time Steinberg worked himself on fresh plaster. The general theme was the labyrinth, and many motifs were developed from his recently published book of the same name; equally present was the city of Milan through a drawing of the busy Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. Over the years the sgraffito was damaged by humidity; the mural was destroyed in 1997 during a building renovation.

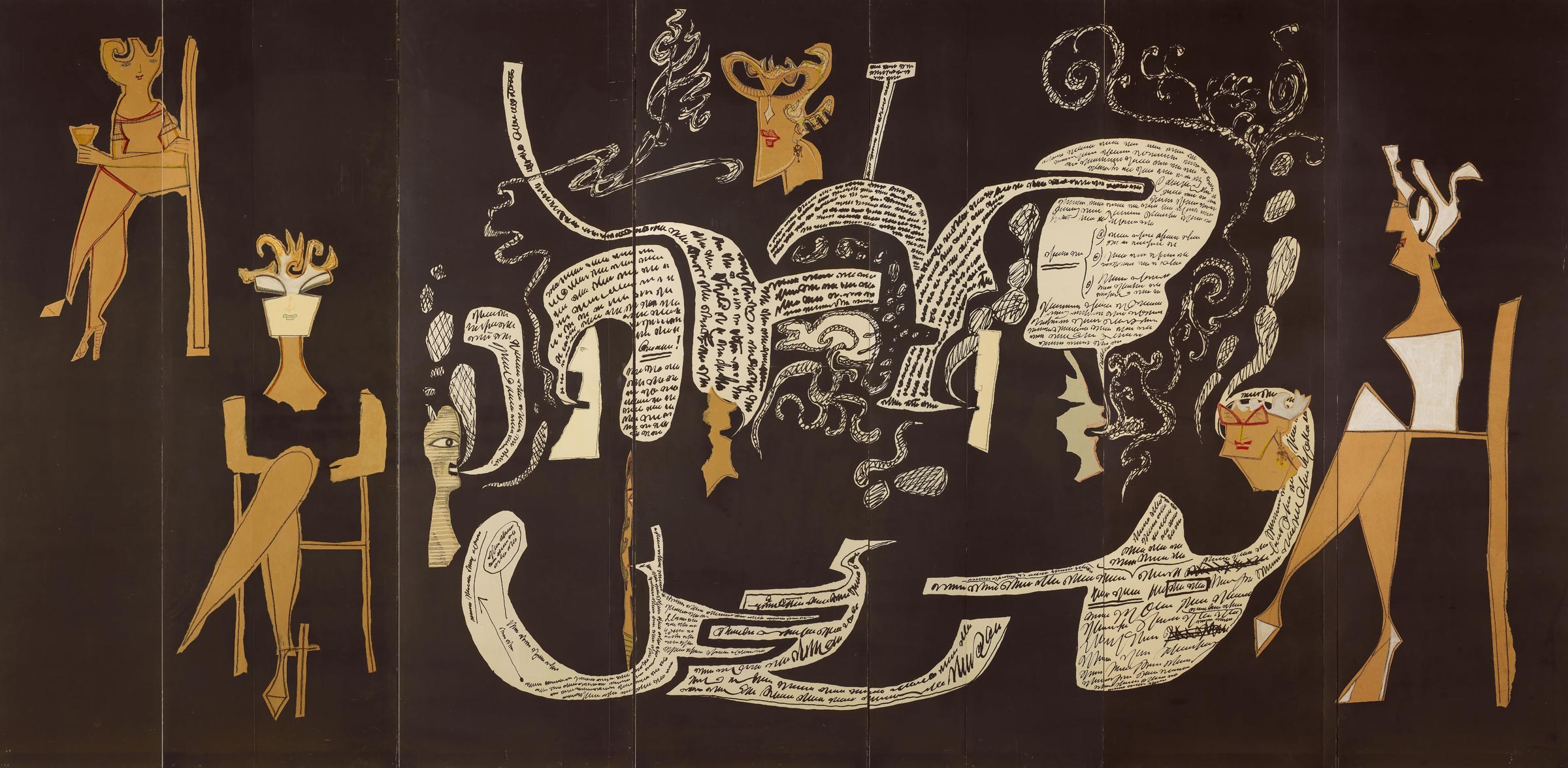

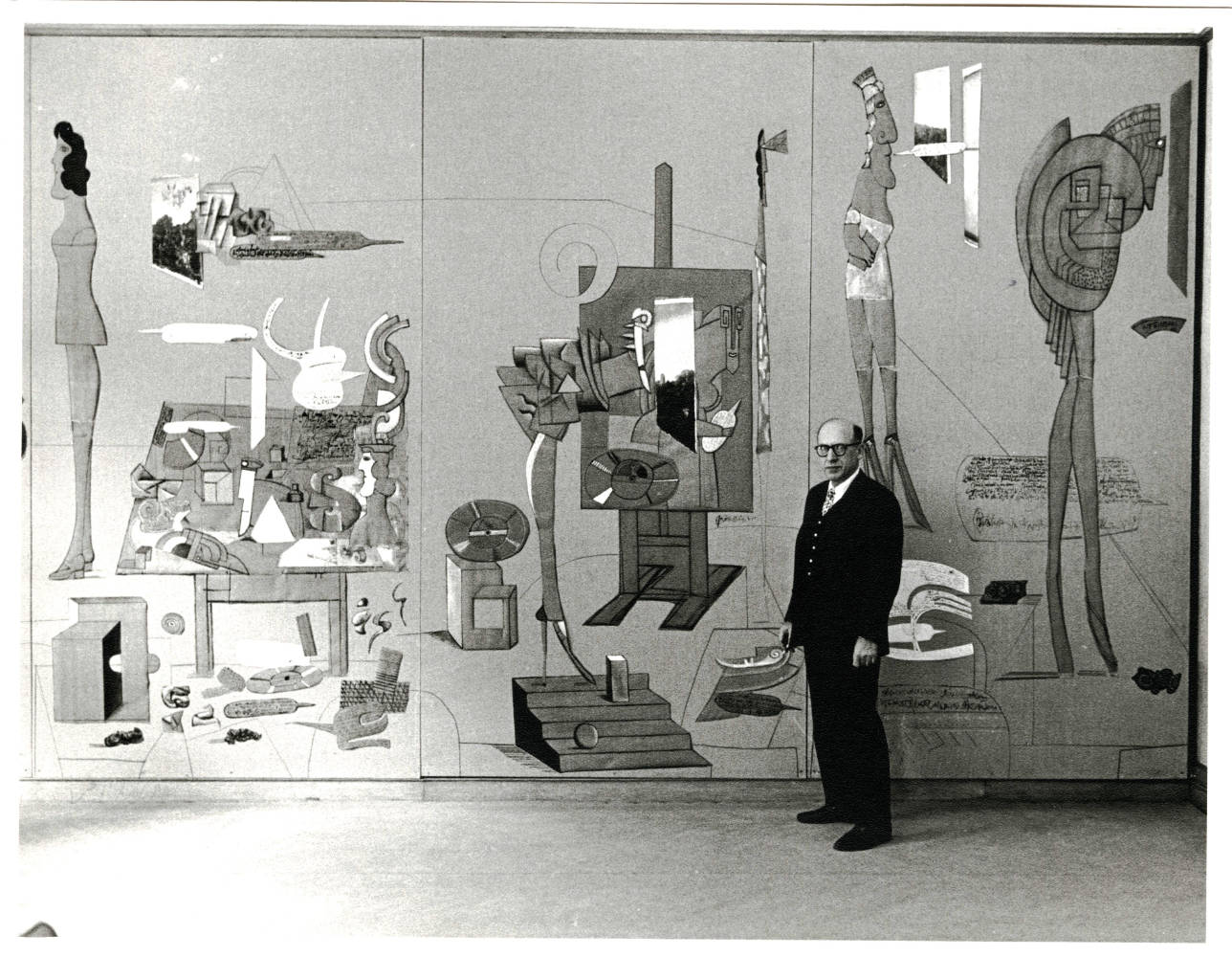

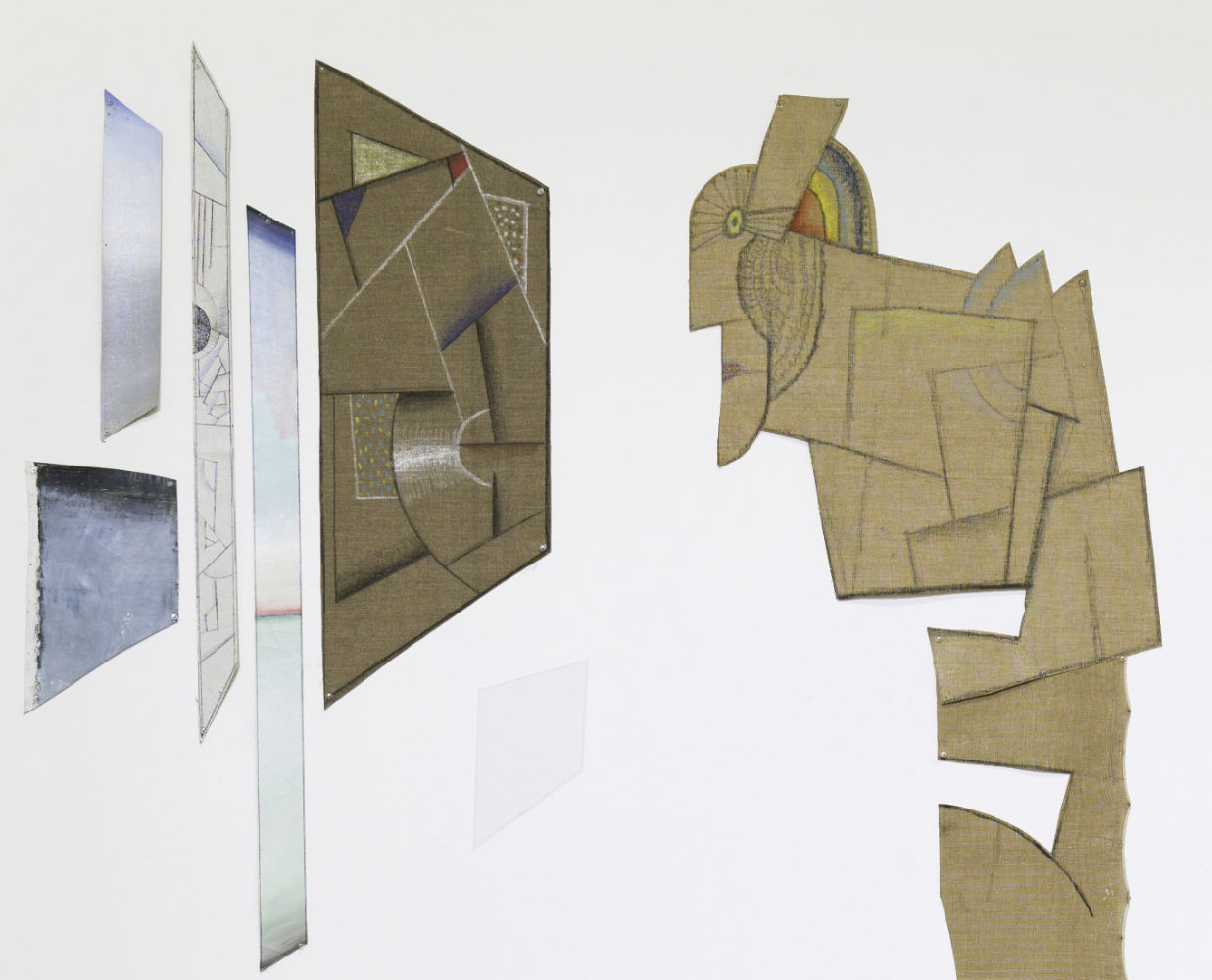

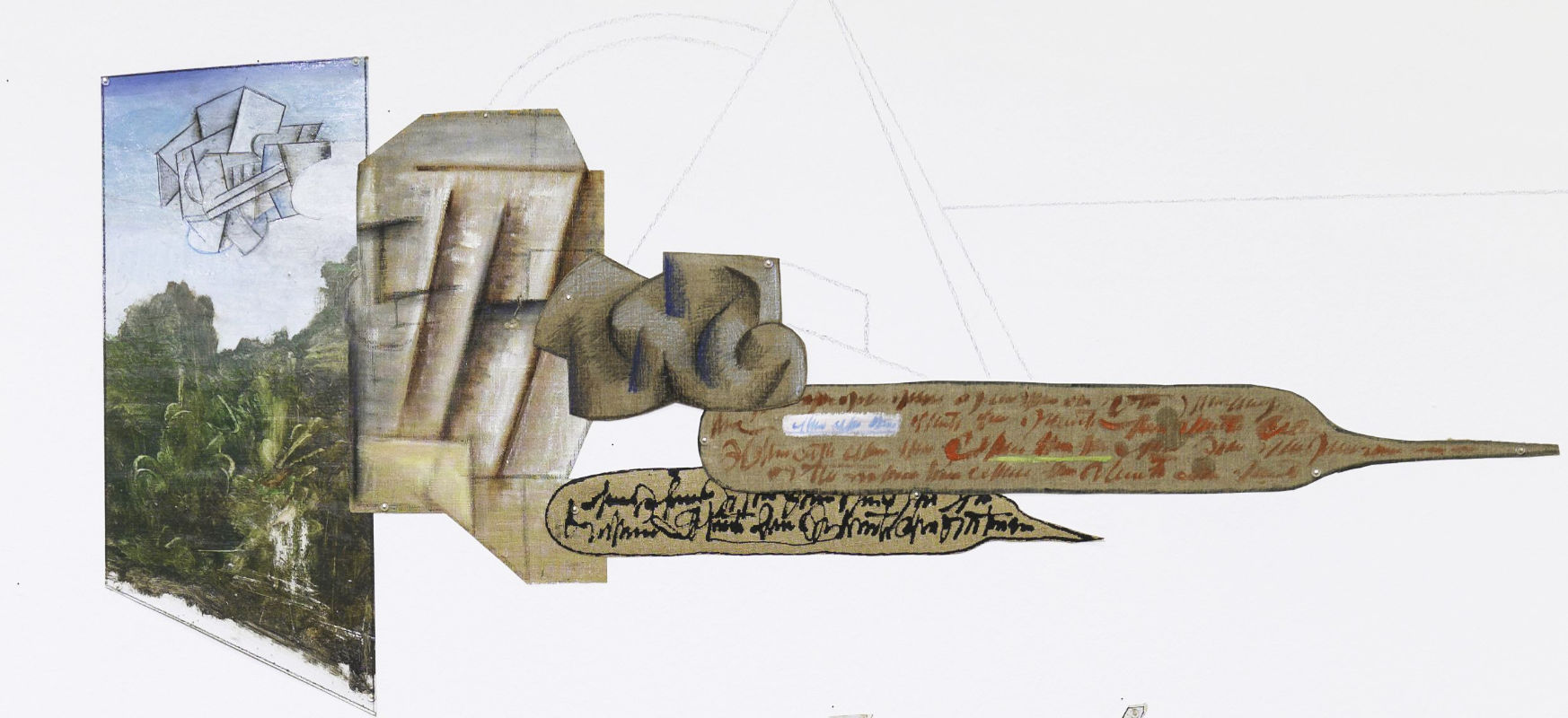

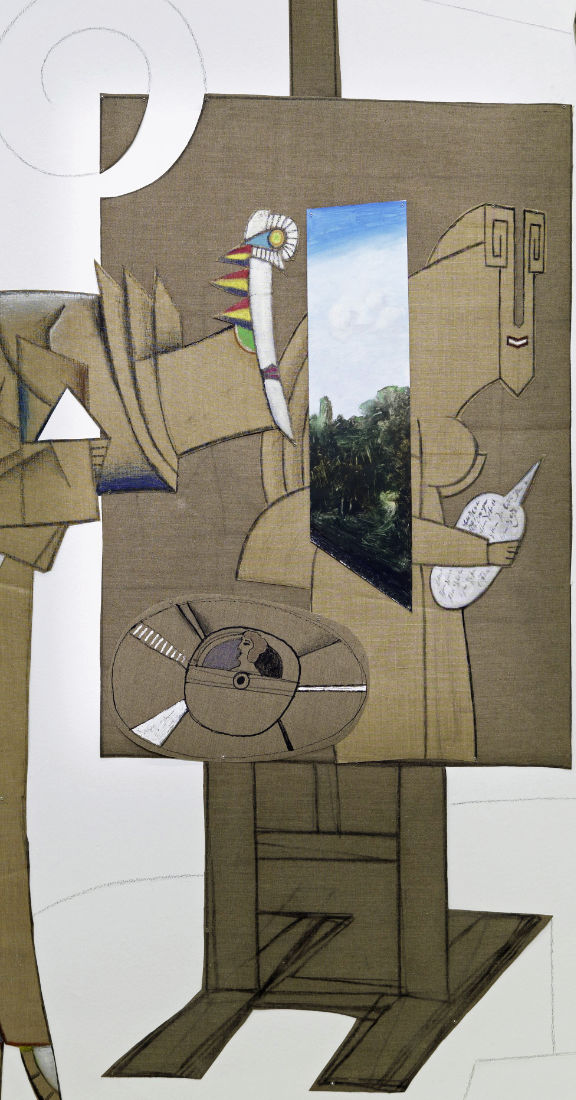

Steinberg’s final venture as a muralist was not designed for a large public space but for a Paris gallery. In 1966, in conjunction with his solo exhibition at the Galerie Maeght, Steinberg crafted a 20-foot-long collage-mural entitled Art Viewers on a wall of the gallery. After the show, the work was disassembled and the ninety-plus pieces, mostly on canvas or linen, were returned to him. Gifted to the Centre Pompidou by The Saul Steinberg Foundation, they were reassembled for the exhibition Saul Steinberg: Entre les lignes at the Pompidou and have since been installed elsewhere.

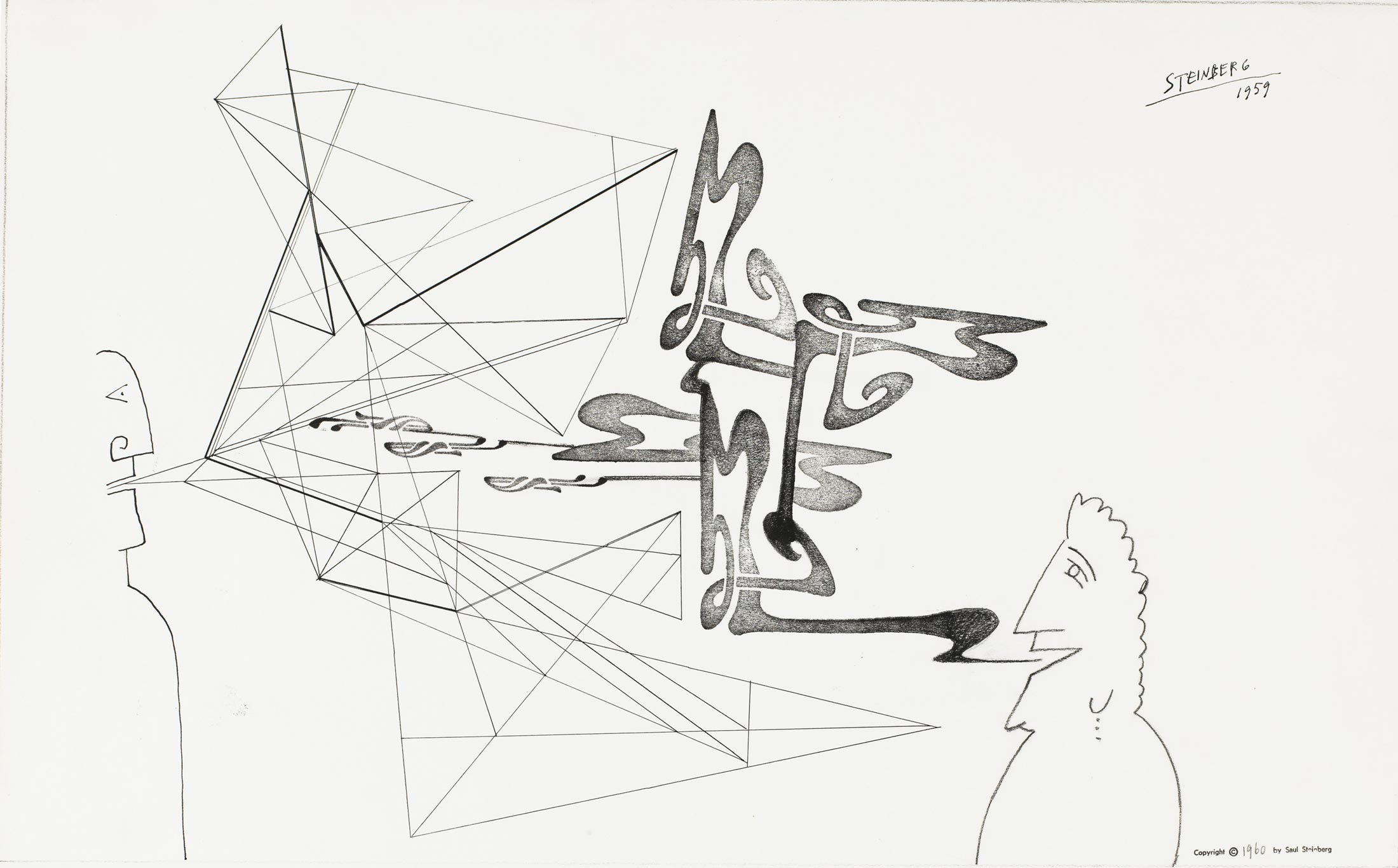

Art Viewers celebrates Steinberg’s lifelong practice of collage. It is also one of his most imaginative and compelling works, the culmination of a twenty-year engagement with the theme of people looking at art. “For me,” he said, “the people who look at art are even more interesting than the art itself.”30A The scale of Art Viewers—human, almost human, and over-lifesize—physically parallels that of the visitors (who, in Steinberg’s oeuvre, are usually female; something to ponder). No longer are they looking at a picture on the wall, but at themselves in real time and space. In a Steinbergian play of reality levels, visitors see a simulacrum of themselves wandering through the gallery looking at Steinbergs, the act of creation represented by the cluttered drawing table and easel—both fashioned from multiple collaged pieces—and by the works being viewed in the mural.

The spectators in Steinberg’s art-viewer drawings are almost always in profile, as they are in the Maeght mural, mimicking the way we see people walking through a gallery. It is here that Art Viewers forecasts the next stage in Steinberg’s adventures in art display. Among the works being viewed, as well as on the easel, are colored trapezoidal paintings. Within two years, he began to create galleries of “false paintings”—minus the people—by assembling works, painted on slats of wood, to simulate the perspectival slant of art seen along a museum or gallery wall. Steinberg is now representing representation, shifting from a focus on viewers to the locus of viewing.